Bocconia frutescens with its inflorescence of single seeded fruit, one of the ‘woody’ Poppies that comprise the genus. Macleaya cordata, from the same family, has a similar look, though topping out at around 8′ and is herbaceous in habit dying to the ground each winter. Another Wiki picture of Bocconia f. growing in Hawaii’ where it has escaped cultivation and threatens the few remaining native landscapes, particularly historically dry and mesic forests.

The title’s question isn’t something we in the Pacific Northwest need to worry about. It will take an awful lot of global warming to make this plant cold hardy here and that may be part of its enticement! I chose this from Jimi Blake’s list…because I am a sucker for cool foliage. Sometimes called the Mexican Tree Poppy this is a Poppy, a member of the family Papaveraceae, a family currently containing 42 genera and 775 species, which is within the the ancient order, the Ranunculales, an order that includes some of the earliest of the ‘modern’ Eudicots to evolve. This doesn’t mean that this species of Bocconia was around at the beginning of ‘time’, or even of this order, just that it comes from that particular genetic line, a line that has been traced back to its beginning, millions of years ago. Recall that every plant, every organism is in ‘process’, that given the appropriate supporting conditions, consistent over time, will keep reproducing, generation after generation…and, that given the appropriate inducements, of consistent, changed conditions, different from those today, will work to adapt to them, each generation ‘responding’, those better adapted, surviving and reproducing, altering the species and, perhaps even becoming, producing, a new one. One of the characteristics of this family and order, having arisen in a time when genetics and characteristics of plants were less strictly defined, is a wider range of physical or morphological variation than you might expect, which is evident when you look at the flowers of the many diverse species within these genera, this family and order…Bocconia frutescens’ small flowers looking very unlike those we would commonly think of when we picture a Poppy.

The flowers, which grow in a large panicle, of 2,000 or more individuals, are apetalous…they have no petals, so you won’t be exactly bowled over when this is in bloom. Maturity takes some 4-6 years of growth and I suspect that ‘clock’ resets if the plant dies back, maybe if it is cut back hard as well. Each flower forms a single seeded fruit commonly eaten by birds, which then spread them. With a mature plant forming multiple inflorescences each plant can form many thousands of seeds each year. The inflorescences are more reminiscent of those of a flowering Rhubarb than a Poppy, but Poppy it is. Imagine any plant stripped of its petals and sepals…their ‘beauty’, their distinctiveness, is in their details. How poppy-ish would a Papaver, Meconopsis or Romneya look without their petals? We must remember that the flowers were never intended for our visual satisfaction, but as part of a plant’s strategies to lure pollinators, and pollinators, in the form of bees do find their way to this plant. It is interesting to note though that these flowers, with their anthers dangling from pendent filaments, also suggests adaptations for wind pollination. The Bocconia spp. and Maclayea spp. together form a ‘clade’, or distinct genetic lineage within the Papaveraceae which are mostly wind pollinated, a shift thought to have resulted after a habitat change. Combined with the fact that the plant takes several years to mature to blooming size it is no surprise that these are grown for their foliage in ornamental gardens, contributing a tropical sense to them.

The flowers, which grow in a large panicle, of 2,000 or more individuals, are apetalous…they have no petals, so you won’t be exactly bowled over when this is in bloom. Maturity takes some 4-6 years of growth and I suspect that ‘clock’ resets if the plant dies back, maybe if it is cut back hard as well. Each flower forms a single seeded fruit commonly eaten by birds, which then spread them. With a mature plant forming multiple inflorescences each plant can form many thousands of seeds each year. The inflorescences are more reminiscent of those of a flowering Rhubarb than a Poppy, but Poppy it is. Imagine any plant stripped of its petals and sepals…their ‘beauty’, their distinctiveness, is in their details. How poppy-ish would a Papaver, Meconopsis or Romneya look without their petals? We must remember that the flowers were never intended for our visual satisfaction, but as part of a plant’s strategies to lure pollinators, and pollinators, in the form of bees do find their way to this plant. It is interesting to note though that these flowers, with their anthers dangling from pendent filaments, also suggests adaptations for wind pollination. The Bocconia spp. and Maclayea spp. together form a ‘clade’, or distinct genetic lineage within the Papaveraceae which are mostly wind pollinated, a shift thought to have resulted after a habitat change. Combined with the fact that the plant takes several years to mature to blooming size it is no surprise that these are grown for their foliage in ornamental gardens, contributing a tropical sense to them.

Woody Stems

This map shows the distribution of species comprising the Papaveraceae around the world. The family occurs most often in temperate areas and is completely absent across vast regions. Bocconia is then somewhat of an anomaly.

Before I get too far into this…what’s the deal with ‘tree’ Poppies? or tree Peonies? or tree Dandelions? or tree Lobelias? or all of those other genera that are comprised mostly of herbaceous perennials with a few ‘woody’ outliers? What’s up with that? In an earlier post I wrote of the small group of species that make up the woody Iris which grow in South Africa. The following was taken from my earlier blog posting, “What is a Species?” in which I gleaned the below from Manning and Goldblatt’s monograph on the group, The Woody Iridaceae: Nivenia, Klattia, and Witsenia : Systematics, Biology & Evolution.

[The woody Irids initially grow their stems in a narrow, pinched, structure, later ‘thickening’ them, adding tissue to the flattened sides of new stems. This thickening does not come from a cambial ‘ring’, there is none in Monocots, but from meristematic cells in the ‘pericycle’ near the primary vascular bundle. This growth occurs in a radial pattern, that includes additional vascular bundles to support the plant’s growth as it adds more leaves and flowers above. Woody Irids produce their hard, often brittle stems, growing them into a more cylindrical structure.

….In convergent evolution, plants from different lineages, that don’t share what might seem to be essential DNA, develop physical characteristics of other, unrelated plants. Outwardly similar, but arrived at from a different ‘path’. The ‘how do these do this’ part is still being researched and debated. In some cases there would appear to be something more ‘basic’ driving the development of plants over the long term building of the given genetics of a plant or group of plants. Structure and capacity are in a sense driven by need. [my emphasis]

When we stop and wonder over an individual Camas or Mariposa Lily, a Coast Redwood or the woody Irid, Witseni maura, it is as if we’ve sampled from a stream of water rushing past us. This is Witseni maura right now! Tomorrow, in an incremental, and perhaps an infinitesimally tiny way, it will be different. When the botanists, taxonomists and systemicists reclassify a species, genus, family or even more basic level of the plant world, the plant itself has not meaningfully changed…only our understanding of it has. When attempting to ‘classify’ something as dynamic as living organisms, how does one decide, what is a species? How different must one plant be before it ‘becomes’ a different species?]

While researching the Woody Sonchus Alliance I came across the research article, Chloroplast DNA Phylogeny of the woody Sonchus alliance in the Macronesian Islands (catchy title, eh!) whose authors suggested that the perennial woody stems are an early, more basal, characteristic of plants, that in their case is a reversion of sorts, genetically coded within it as an Eudicot which sprang from earlier Angiosperms, and before them, Gymnosperms. All organisms contain what some refer to as redundant, strands of variant DNA or alleles, or ‘copies’, while much of an organism’s DNA is often referred to as ‘junk’ DNA, whose purpose is unknown, and to our understanding, without purpose, both of these lying dormant without an apparent role to play. Through the process of adaptive radiation these plants, isolated as they have been, were able to take advantage of the genes suppressed by most of the genus to fill an open niche in the Canary Islands. Does this ‘extra’ DNA provide for the possibility of adaptation, a repurposing of old patterns? This may be a similar situation within Bocconia.

Unlike the woody Irid alliance, eudicots like the woody Hawaiian Lobelioids, the woody Canary Island Sonchus and Mexico’s Bocconia frutescens, utilize their different internal stem structures to grow their woody stems. At some point you may have learned that eudicots, the more recent redefinition of the older, problematic dicot group, are defined in part by their capacity for secondary growth from their cambial tissue, adding girth, incrementally, to their trunks and branches….While this is true, herbaceous eudicot species ‘shed’ their above ground structures when they go into dormancy and regrow them in Spring thickening their stems as the lengthen through out their single growing season. Eudicots with a ‘permanent’ above ground structure add both girth and length each year. For woody eudicots the difference between species is primarily of scale, plants being simply limited by their genetics staying small, adding to their girth in a less substantial way vs the more ‘open ended’ growth of larger trees. This growth is also limited by age, as when plants pass through their maturity quickly and then expire. The stem structures themselves vary considerably amongst the diverse species within the eudicots. Some stems are hollow, some have a soft, pithy, center, different structures that more closely resemble the pattern found within the ‘stele’ of eudicot seedlings, the pattern first exhibited in the vascular system within the soft juvenile growth of a seedling’s first year. A plant’s stem growth, gives it stature and thus strongly impacts the conditions under which it may grow. In a sense a given species, this Bocconia f. is ‘obligated’ to its plant community to fulfill its distinct habit and structure in order to fulfill its larger role. Change that community, move that species to a different landscape…and the species will continue as it had before, though under new pressures, pressures that over coming generations will change it.

Bocconia Evolution and Kin

Bocconia, is a genus of approximately 9 species limited to Mexico, Central, South America and the West Indies which may be distinguished from other members of the family by its woody, shrub to small tree-like, versus herbaceous, habit and may be considered atypical due to the apetalous flowers and a 1-seeded fruit. It does in fact look very similar to the far more commonly grown Maclayea cordata, or Plume Poppy, in our temperate gardens. Some botanists have placed these two species together in the past…but, M. cordata comes from China and Japan. Evolving as they did on these separate continents, which have been divided from each other since Gondwana broke away from Laurasia during the Mesozoic, a process that began between 200 and 170 million years ago…there has been little opportunity for the ‘sharing’ of genetic material between them. Given that these plants, even the earliest of Ranunculales species, evolved after this separation….

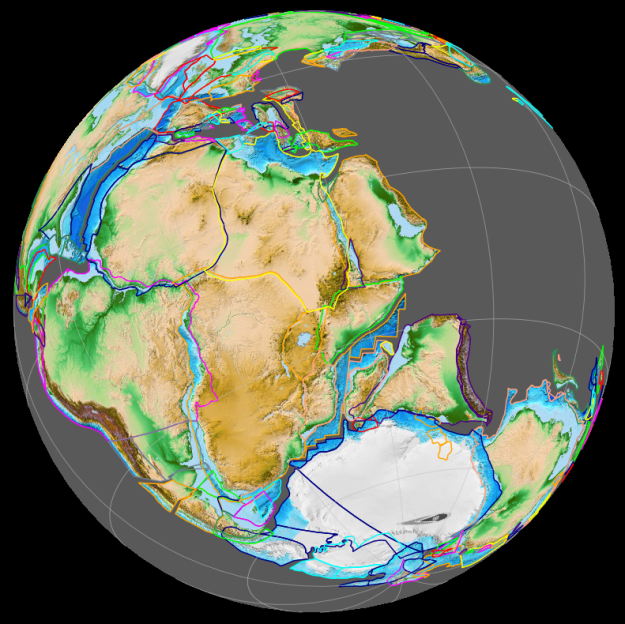

This is a schematic of Gondwana 150 million years ago (Mya) after Pangea separated into Laurasia, to the north and Gondwana to the south and the present day continents of South America, Africa, Australia and Antarctica have begun to split up. The dark blue to the upper left shows the expanding Atlantic Ocean which is beginning to form between South America and Africa. These southern hemisphere continents are rifting and beginning to separate from Antarctica. The sub-continent of India is also splitting away from Africa to begin its northeasterly journey.

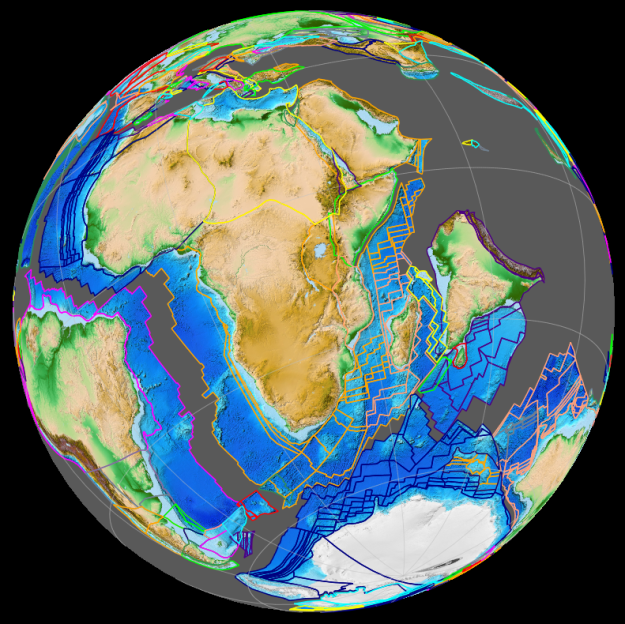

This image shows the same region 70 Mya as the continents continue to separate and India, picking up speed, begins to open the gap for the Indian Ocean to form in-between while Madagascar remains roughly in place relative to Africa. Over this entire period Mexico and Central America are more and more isolated from east Asia, completely cut off in terms of an exchange of genetic material. It is thought that the plant Order, Ranuncualales, which contains the Poppy Family, first began to distinguish itself from other plants between 110-140 Mya. Papaveraceae is dated around 119 Mya to 106 Mya. This suggests that Bocconia spp. which developed many millions of years later evolved separately from other family members in Asia, Africa and Europe.

Maclayea cordata is a much hardier plant, having evolved in a more temperate climate and has since proven to be quite capable of spreading around our gardens, which is why I’ve never invited it into my own. If I had a more ‘confined’ area I might have included it. There are other plants I have brought in, like Romneya coulterii, another Papaveraceae, and Anemone x hybrida ‘September Charm’, with a similar propensity to spread and dominate…and then got rid of them with some effort, serving as a warning for me when considering such aggressive spreaders, however beautiful I found them to be. I like some degree of control in my garden and want to be able to shuffle and change plants without undue stress and worry, there is plenty of that already.

Growing Bocconia and the Issue of Invasiveness

A friend recently asked me about ‘exotic’ plants, non-natives, and their propensity to become invasive. I told them that exotic and invasive are not synonymous, that ideally, hopefully, nurseryman do their research before they introduce a plant new to a region to avoid the problem, because once introduced and established, an invasive plant will likely be with us for the foreseeable future. No one wants to be responsible for introducing the plant that becomes the bane of a region’s population, neither gardeners nor the rest, but it does happen. A plant becomes invasive if it is able to take advantage of the niches and conditions available without the controls that keep the members of a plant community in balance with each other. This may include an absence of insect pests and diseases, that would normally work in a limiting way across their native region. Invasives are generally capable of readily increasing both by seed and vegetatively as bits and pieces, root and spread readily. Many are prodigious seed producers and, very often, the ungerminated seed of these can last for many years in the ground and so provide a source for re-invasion from within this ‘storehouse of seeds’, the ‘seed bank’ within the soil itself, even well after the particular scourge has appeared to have been controlled. One of the problems with invasive plants is that they tend to dominate a landscape and grow densely, often literally choking out any native or other exotic competitors. Some plants can be thugs in our gardens, but aren’t necessarily invasive, though they share similar characteristics, without the ability to escape into landscapes in which most of the growing conditions are undisturbed. In the plant world supplemental irrigation constitutes a disruption as it enables and supports certain plants over the native community. The capacity of a given plant to be a ‘thug’ or invasive varies from region to region, even between ‘landscapes’ within them, because the growing conditions within them may.

I bring this up here for two reasons, one, it is a pet peeve of mine when someone says a plant is invasive, as if it is a built in quality of a species…it is not! Invasiveness is a result of many different factors, factors that vary across the landscape. In general, native plants will not prove invasive and domineering…in their native region, though some come close to this especially in disturbed/urban/developed areas where landscapes, the plant communities and relationships within them and their conditions, are more simplistic and homogenous. Our tendencies as western/civilized people predisposes us in particular ways, through our designs and the lack there of, as well as our plant selections and cultural practices, how we garden and treat the wider landscape. All of this contributes to the ‘pattern’ that selects for and supports the weeds that plague us. Think of Horsetail and Canada Thistle, two western natives that can over run regional landscapes. Again, invasiveness is not an inherent quality of a species. To treat them as such is a reflection of our ignorance which ultimately boils down to our relationship with the living world and the landscapes we occupy. A given species may be invasive in certain type of natural landscapes in a given region…but not in another. All species have particular relationships that they may require, be they with other species or the growing conditions. The more ‘general’ a species requirements are, the better adapted it may be in its ability to ‘invade’ a given landscape. I will often hear gardeners from other regions, with very different conditions than those here, warn against a species that is invasive for them…each species, each region and landscape has different requirements and present different conditions so such general advice is often not helpful and in simplifying the problem, generalizes the problem and helps cloud our understanding of the living world. While such advice might seem helpful, and I’m sure that the intent is to be such, it really isn’t.

The Centre for Agriculture and Bioscience International, CABI, has an incredible website which includes their Invasive Species Compendium listing a great many species that have proven invasive in different areas around the world. The information it presents is exhaustive, one of the best such sites I’ve come across. I’ve linked to their entry for Bocconia frutescens. In addition to its description of the plant it lists it describes the type of habitats a given species typically can occupy, how it spreads, its biology and ecology, information on its natural enemies. It is a great site to check out before you acquire a plant new to you and especially one that may be new to your region. It will answer many questions you have likely not even though to ask, which can be very important. This same information can also help you decide whether your particular landscape can be at least supportive enough of the plant to grow it responsibly and consistently. Keep in mind that an invasive plant does not mean that it is invasive everywhere, that every plant is native somewhere and that a plant that can be grown responsibly in a garden can add value to it.

This is a flowering Bocconio frutescens that has invaded the old dry forest region on the Auwahi of Maui. Not very picturesque or garden worthy as it grows here, but this speaks to its ability as an invader.

The following paragraph is quoted from the CABI website:

Bocconia can grow on a wide variety of soils and habitats, ranging from subtropical dry forests along streams to subtropical moist and wet forests of Puerto Rico. It is most commonly found along streams, road cuts, and landslides, but also occurs in abandoned pastures and secondary forest. In Nicaragua, it grows in cloud forest and in Costa Rica, it occurs in mesic to wet regions, in second growth and open sites as well as along roadsides. Bocconia frutescens is proving to be an invasive plant in dry to mesic tropical and sub-tropical areas and forests…

In Hawaii, where it can dominate choking out native species it has been listed as a noxious weed and is prohibited. As a weedy pioneer species it is spreading in more tropical and sub-tropical areas of Central and South America quickly invading disturbed sites, a condition that is increasingly common around the world due to urbanization, agriculture and our spreading transportation infrastructure…and it is doing this across a wide elevation gradient comparative to its range in Mexico. In Hawaii, with its southerly latitude, on the islands of Maui, the Big Island and Oahu, this is becoming more commonly found at elevations from 488m to 1220m, or 1,600′ to 4,000′. It has reportedly gained a foothold in warmer parts of New Zealand as well and the nearly 1,00- sq.mi. of Reunion Island off the coast of Madagascar where it has likely escaped from gardens. In the cool temperate NW Bocconia frutescens will never do this. To our south some are saying it is hardy enough for zn 9b gardens, but has yet to demonstrate that it will escape…an observation that maybe true today, but perhaps not if the plant begins to be more commonly grown. It is possible that the seed has simply not yet reached sites that are amenable to germination and establishment. Something to be carefully watched.

Bocconia frutescens is a native to the highlands of Mexico, like those in the Sierra Gorda Biosphere Reserve, in Queretaro, Mexico, some 100+ miles north of Mexico City. It often grows as a scattered member of a mixed understory community reaching as high as 15′-20′, never dominating. Elevations within the reserve vary from 650′ to over 10,000′ with precipitation that ranging from 14″ – 79″, and include the following plant communities: Tropical Evergreen Forest, Tropical Sub-Deciduous forest, Tropical Deciduous forest, Xerophyllous Shrub, Oak Forest, Conifer Forest, Pine-Oak Forest, Cloud Forest, Riparian Forest. Bocconia f. is particularly well adapted to the drier communities there.

Below 25ºF, zn 9b, will likely prove fatal for this so that any thought that it will be invasive here is extremely unlikely. Its cousin, Macleaya c., which can be ‘thuggish’ in the garden, has not been, to my knowledge, capable of escape here either. Growing either would seem to have little to no direct consequences for the wider landscape.

This suggests that if you’re going to plant experimentally it makes more sense to plant plants that are either tender or marginal here, that cannot survive outside the pampered confines of your garden. Bringing in exotics that are well adapted to our conditions, plants that many gardeners are seeking because they may be low or no care, are potentially much more dangerous to other landscapes, native, neglected and the minimally maintained. If we choose these plants, especially if they require no supplemental water in summer, than we should be especially careful in our choices, limiting our use of the most aggressive spreaders and focusing on natives and other species that are already found here along the west coast of North America, plants I sometimes refer to as ‘west coasties’. If we limit our choices to the Rocky Mountain Floristic Region or Province, a region that covers the area from Kodiak Island in Alaska south to San Francisco Bay and east to the Sierra Nevada into the Rockies, we should be safe. Plants like Bocconia f. will require ‘coddling’ and will not survive without it. When we look beyond these areas for plants, we need to be much more thoughtful than we often have been in the past, which means that we need to strive to be more thoughtful gardeners.

Okay, then, having said all of this, would I grow it? yeah I would, but not right away, because I have too many other plants that require that I protect them in some way already during our winters, and they deserve their opportunity. Second, like others have noted elsewhere there are easier plants that contribute very similar characteristics to the garden like Hydrangea quercifolia, which has always had a place in my garden. Still it could happen. Its attributes are obvious to me.

This is still a hard to come by plant. San Marcos Growers in California is producing it saying that it has not demonstrated an ability to escape and invade in California’s mediterranean climate. Crug Farm in the UK also lists it. Plant Lust lists no sources. The lesson here is that if you want this and see it at a specialty nursery…buy it, because it could be some time before you ever see it again!

For other perspectives see the following two blog postings. Danger Garden. The Outlaw Gardener.

My bocconia has had a tremendous bloom this fall/winter and is continually covered with bees. It’s about 12 feet high now, and this year is the first I’ve noticed seedlings at its base. It needs supplemental water in summer to look its best here in SoCal, zone 10. The photos of the ratty-looking specimens in Hawaii are eye-opening. Mine has a lovely vase shape at the moment from attentive pruning. So many good points you raise on the situational aspects of “invasives” — thank you!

LikeLike

I’m looking for a T-Shirt for you for Christmas that says? “Ask me about Bocconia frutescens”

LikeLiked by 1 person

My plant was killed to the old wood again when we had an unexpected dip into the mid 20’s last winter. I would have brought it indoors, but like I said the dip was unexpected and so ZAP, it was gone. Thankfully growing bits re-sprouted in a couple of places and it looks good again, although there won’t be any blooms (or seed) this year. If I get seed next year you should try growing it. The seed seems pretty easy to germinate.

LikeLiked by 1 person