Roldana petasitis var. cristobalensis shown here looking amazing with Aeonium arboretum ‘Zwartzkop’. Its substantial leaves are some 8″ across, thick and velvety, the undersides of which are red/purple, like the stems. The color often comes through in the veins along the top surface. A very striking foliage plant. Picture this with its close relative, Pseudogynoxus chenipodiodes, the Mexican Flame Vine, formerly known as Senecio confusus!

Sometimes called Velvet Groundsel, this plant has been living and marketed under several different names. The first name in the heading is the one Jimi Blake ascribed to it, a name I didn’t recognize for a plant I’ve grown off and on in the past…it got lost in his list paired with a particular Thalictrum and I simply missed it…until recently. I knew it as Senecio cristobalensis and, had I recognized it, would have included it with an earlier post in which I focused on his favorite Asteraceae. I did actually mention the plant there simply as another Senecio that I’ve grown of value. Here I shall treat it more directly. The genus, Roldana, was recircumscribed in 2008 to include some 54 different species. Other authors include as few as 48 and as many as 64 in the genus, most of which used to belong to Senecio and are native to the extreme Southwestern US, Mexico and Central America. Most of the Roldana species are somewhat ‘shrubby’ herbs with a few, like this one woody, even tree like. Both genera are within the Asteraceae and share tribe status as well, Senecioneae. For the curious, Roldana spp., even more finely, are included in the sub-tribe, Tussilagininae, which includes the very commonly grown genus of garden plants…Ligularia! On closer examination the morphological similarities will begin to stand out to most of us. Check out all of the photos on the Wikimedia Commons page for Roldana petasitis. Roldana petasitis is the correct species name for this plant. With all of the shuffling and consequent confusion still going on in the world of taxonomy, especially in such a mixed large genera like Senecio, we must all be allowed our mistakes of nomenclature. It is a volatile changing world out there.

Roldana petasitis growing in the Jardín de Aclimatación de la Orotava, a botanical garden on the island of Tenerife, one of the Canary Islands, a garden and place I’d love to visit sometime. from Wikimedia Commons

A flowering ‘head’ of Roldana petasitis with 5 ligulate ray flowers surrounding its simpler disk flowers.

The species, and its three recognized varieties, are concentrated in the tropical mountains of Chiapas, south into the Guatemalan highlands. Much thinking supports the idea that the progenitors of Roldana moved south out of North America. Fewer species are found as you look south especially at lower elevations. Plus Roldana appears to share more in common with the North American flora than that of the south. Tropical species tend to occur below 1,200m in Mexico and share more genetically with the South American flora. Many other Roldana species range north into the Sierra Madre del Sur along the central west coast, north into Oaxaca across the length of the Trans-Mexican Volcanic Belt, the range of snow covered mountains that cuts east/west across the country near the latitude of Mexico City, bounding the lowlands of the ‘Isthmus of Tehuantepec’ [tewanteˈpek], where the North American plate and the cordillera ‘breaks’ along the edge it shares with South America, the narrowest part of Mexico. Other species extend north in both the Sierra Madre Orientale and Occidentale. R. petasitis occurs with quickly diminishing frequency moving south through the highlands of El Salvador, Honduras and Nicaragua though the mountains continue on to Panama. For a closer look at the genus check out this paper, “Taxonomic Revision of Roldana (Asteraceae: Senecioneae), A Genus of Southwestern U.S., Mexico and Central America.” [Apparently this link doesn’t work anymore! It did when I did my initially research for this posting. I don’t understand why so many publishers of scientific papers require a subscription by an institution to access their documents? It’s not like there will ever be some huge readership. I just like to go to the source to read this stuff.]

Genus Roldana is thought to have arrived and speciated as a result of long term climate fluctuations, the thousands of years long warm and cold periods of the Ice Ages of more recent earth history. With each advance and retreat of glaciers, the ice cap moved south pushing the leading edge of the cool temperate forests ahead of it, compressing the tropical regions into an ever smaller area. This was exacerbated by the simple narrowing of Mexico’s land mass. During warm cycles the ice and cold retreated northerly, drawing in more tropical flora from South America. In Mexico’s mountainous areas the temperate flora moved upwards seeking the cooler temps they required, as the warmer/tropical flora filled in the lower elevations ‘drawn’ in from the south. This, cyclic, ebb and flow of species was common along this band around the earth. This resulted here in Mexico with ‘refugia’, havens, of montane species scattered and disconnected at the southern extremes. This also speaks to this entire genera being montane today occupying and extending up through both the Sierra Madre Orientale and Occidentale. The isolated populations, unable to share genetics, began to vary over the centuries and millennia resulting in a kind of genetic ‘drift’, and discontinuous populations of ‘new’ species and varieties. While some of the species are more generally widespread many are not and the various ‘islands’ have often become ‘home’ to small, restricted endemic species and populations…like Roldana petasitis var. cristobalensis.

Roldana petasitis var. petasitis, the most common form, has the broadest range, and can be found from Vera Cruz in the north, south into Nicaragua, in both Pine-Oak and Mountain Cloud Forests between 1,000m and 2,500m. The species, like many others in the genera, tend to occupy understory in mixed pine/oak forests, a biome that is common throughout mountainous Mexico north into the southern Rockies of the U.S….

[As a side note, Mexico is one of the centers of genetic diversity for Quercus, the Oak genus, and is home to some 160 of the world’s 600 species, all of them in the northern hemisphere, 109 of them endemic to Mexico. Recall that the Pacific Northwest has only four Oak species, three limited to the southern extreme of Oregon which range into northern California. ]

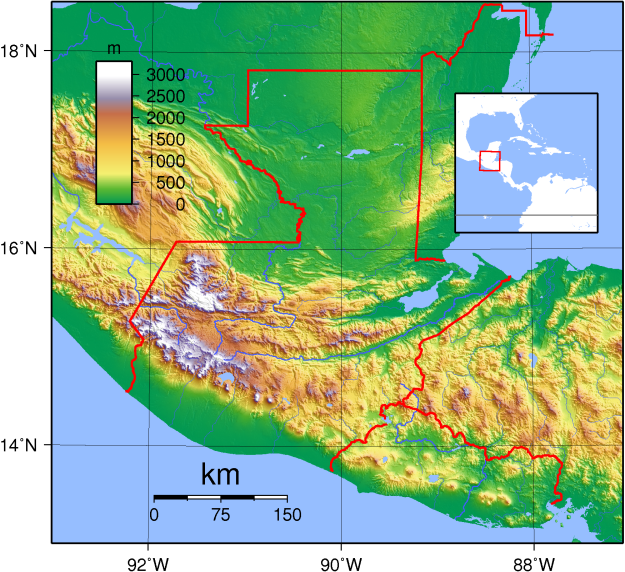

This map shows Guatemala, bordered in red, in the middle with Chiapas to the left. Roldana petasitis var. cristobalensis is restricted largely to the lower mountainous areas in this region, up into the ochre color range of the scale, most commonly on the eastern facing slopes of the mountains where it is somewhat drier. I’m not sure exactly where this might grow under ‘mountain cloud forest’ conditions as the elevation band is on both the western/wetter and eastern/drier sides of the mountains. I did find that the wetter/western slopes can receive some 80″ of rain a year which would seem to be too wet for R.p. var. cristobalensis. The Iimiting Isthmus of Tehuantepec begins at the far left edge of the map.

Jimi’s plant is not the species but the variety R.petasitis var. cristobalensis. This naturally occurring variety has a more restricted range and was found and described from plants in Chiapas, the southern most Mexican state, and in Guatemala. At around 16º north latitude, this puts the area well within the tropical band that wraps around the earth. Its mountain locations moderate its tropical location somewhat. This variety is found generally between 1,000m and 1,600m, lower than most of the other species and even lower than the other forms of this species, in mountain cloud forest. This makes R. p. var. cristobalensis a bit of an anomaly. The Oaxacan variety occupies an elevation band higher between 1,400m and 2,000m from Chiapas north into Oaxaca and Vera Cruz…in Pine Oak Forest. Roldana p. var. sartorii is the most northern population, occurring only north of the Isthmus of Tehuantepec into the Trans-Mexican Volcanic Belt and is differentiated by several physical characteristics including an almost complete absence of pubescence on the undersides of its leaves and stems. It is found in Pine Oak Forest between 1,200m and 1,800m.

Some botanists think that because irrigated agriculture has been practiced in this region for an estimated 6,000 years and the people who practiced it did so where they lived, the greater part of them in the Pine-Oak Forest areas, that people have likely played a role in the more recent evolution of these plants and certainly where they are found. The entire genera is somewhat promiscuous, ‘weedy’ and will readily occupy disturbed sites.

I had to include this: In the 1880’s, while the competing Panama Canal proposals were made, others were trying to build a railway across the Isthmus of Tehuantepec that would carry ships the 130 miles, by rail, which would have been a very considerable economic boon for Mexico. The Isthmus had always been a significant trade route. It didn’t happen, at least not like first proposed. Among other problems, much of the northern portion of this lowland ‘passage’ is swamp and presented insurmountable foundation and construction problems. A more conventional railway line was eventually completed in 1907.

I wanted to include a climate map of Mexico. This one utilizes the classic Koppen system designating the various climates based on temperature, precipitation and their seasonal patterns. Here it has been modified by Mexican climatologists to better reflect Mexico’s complicated geography…even so, because of the abrupt changes in elevation, and its rugged land forms, different climatic conditions can occur in close proximity to one another. Mountains can create wetter and drier areas and extremes that are lost on a map of this scale.

The region of Mexico containing the native range of Roldana petasitis is shown on the above climate map as ‘Tropical wet/dry’ with scattered areas of ‘Semi-arid’ and ‘Temperate with dry winters’. The species grows outside of the dark green ‘Tropical wet’ areas. The Semi-arid areas tend to receive their rainfall in summer some of which are located on rain shadow areas of both the Sierra Madre de Chiapas and del Sur on which the heaviest rains fall on their coast facing slopes. Semi-arid in Mexico is interpreted to mean wetter than desert, between 10″ and 30″. Roldana petasitis var. cristobalensis appears to primarily occur in Tropical wet/dry areas shading into the drier either semi-arid and temperate wet/dry areas where they transition from one to the other. Cold and dry are definite limiting factors especially as you look north as are year around warm/wet to the south.

The Koppen system classifies Portland as Csb, dry summer sub-tropical or commonly, mediterranean. Averaging all the highs and lows throughout the year our temperature is 54.5º F. Our average minimum daily temp occurs in December and is 40.4ºF while our coldest average minimum low temp is around 35ºF. Yes, our extremes can very considerably further than this, but that is not what climate is based on. Climate presents the conditions that a plant most tolerate on a regular basis. This is not to say that our cold extremes don’t matter, they do and success growing this will require that we take some kind of protective action, at least during those periods with these colder extremes. It is not just the extremes that are important, however, but their duration. The effects of temperature are accumulative. Moving beyond a given range a plant is put under regular stress and is compromised. Plants here must tolerate cooler conditions, longer than those presented in this plant’s range in Mexico and Guatemala. We must protect them from these cold extremes in order to keep them within their normal low range.

Our annual rainfall total, here our average is 36″ measured at PDX, mine in inner southeast Portland is generally higher, as much as 5″ or more over a year, itself is not too much, but the fact that most of it falls over our colder winter months, with very little occurring during our warm summer months, is an issue. As noted above across Roldana’s range the drier months tend to be during their cooler, but not cold, winters. This difference is significant and requires some kind of compensations and adjustment to grow it successfully here. Improving drainage will help these in our wet winters as will adding supplemental water in summer, especially during our hotter extremes. Always remember that stress can reduce the range of what is considered normal. Saturated wet winter soil will reduce Roldana’s ability to tolerate cold just as stressing it during summer with inadequate water will bring it into the fall weaker. As gardeners, whatever we choose to grow, we must respect the plant’s requirements.

Typically occurring as an understory plant I would suggest that here, it be planted in a protected location, in sun, though perhaps with some afternoon protection during our hottest driest periods. Remember that these, with their tropical latitude and elevation, normally experience overall more moderate temperatures than we can typically offer it. Such a placement will also aid it during our cool wet winters giving it adequate space and air movement for the plant to best avoid fungal problems on its top growth. It’s dense cover of ‘hairs’ can collect and hold moisture. If it’s potted for the winter it can easily be store outside under a roof which will both keep it drier and protect it from the extremes of radiant heat loss it might experience growing out in the open.

San Marcos Growers in California rates this as a zn 8b plant that can retain its above ground structure down into the mid-20’s and rebound from its roots down to 15ºF. Annie’s Annuals rates it more conservatively as a zn 9a plant…dying at 20ºF. Sean, out a Cistus, rates it as root hardy to 15ºF, zn 8b. Mountains, semi-arid, wet/dry, tropical latitude at higher elevation…I lost this plant over two different winters in my garden outside…though I didn’t record which winters or what conditions it had to endure, so I can’t ‘weigh’ in on these grower’s claims. They were planted in a mostly flat area of my garden in Willamette Valley, Latourelle Loam that I hadn’t added any grit to to improve drainage. One of those falls I made a half-hearted effort to root cuttings, which failed. Even the new growth on these is quite thick and ‘hairy’. My cuttings appeared to have succumbed to some kind of fungus. I’ve had success with multiple other zn 9a and 9b plants when I dug and potted them for storage during our coldest periods in the limited space I have in my basement. I grow Salvia chiapensis, a zn 8a neighbor, naturally occurring a little higher in the mountains of Chiapas, out in the garden in the same general area where the Roldana previously failed…This winter it hasn’t stopped flowering. Normally I dig it or take cuttings. I have rooted cuttings in the basemen now.

In its home range Roldana p. var. ‘cristobalensis’ can grow to 10′ spreading to 8′ across…which would make a pretty spectacular sight! with its fine, densely hairy ‘red’ stems and dark, felty, rounded, palmately veined leaves with their ‘red’ undersides. This is a unique and beautiful plant. I grew it at the same time as I was experimenting with several different Solanum spp. some of which echoed similar characteristics, like the curiosity Solanum quitoense. Others of that time included Iochroma, Cestrum spp. and cultivars…all of which visually played well together. All and all this is a very ‘fun’ group of plants and, with a little extra effort and thoughtful monitoring, these are successful.

(A note here, with our current anomalous winter (’18-’19), I’ve experienced freezing only twice, both times, just barely, once 31º on Jan. 1 and 32º on Jan. 2. Forecasts for the next nine days, it is Jan. 8, predict no freezing temps and the long range forecast through April sees slightly warmer and drier than normal conditions, our ‘normal’ minimum for January being 35º-36ºF. I could actually be in the midst of a zn10 winter without a recorded low below 30ºF! Out at PDX they’ve experienced freezing on eight different dates this winter, only one time dropping down to as low as 29ºF, putting it solidly in zn9b! This would definitely have been a year to have grown this!}

(February took a decidedly colder turn as we recorded repeated freezing temperatures, generally limited to the mid to upper 20’s.)

________________________________________________________________

It is now late July 2020. We’ve had another mild winter at my house, one time reaching down to 26ºF in late November. It has also been a much drier than normal year so far with June receiving roughly double our normal rain and normal temps, most of the rest of the months receiving below or just barely normal rainfall amounts. For our rain year, Oct. 1 – Sept. 30, we are at about 75% of normal with a little more than two dry summer months to go. None of this particularly matters to my Roldana because I dug it late November just before our predicted first hard freeze and I was uneasy about what the winter to follow would bring. My plant may have been okay in the ground….

It wintered easily in its pot spending most of it outside under roof. I ‘chunked’ it out roughly, not attempting to include much of a rootball the soil being loose anyway. It had to be supported to keep it stable and minimize damage to roots. I brought it into the basement a couple times when lows were predicted to drop below 30ºF. It did fine giving it a considerable head-start over a new plant when I planted it out in April with its two 3′ stems. I did not cut it back at replanting, but did support it with bamboo stakes until it could get its supportive roots back out into the soil. Our spring temperatures were average for us, mild, with no freezing and, again drier than normal, April receiving less than 1/3 of our normal 2.73″. It re-established and has since grown to about 5′ wide and just under that in height to this date, with multiple stems and large fuzzy leaves clothing it to the ground. I’ll be keeping my eye on the long range forecast with the intent of leaving it out all next winter, barring arctic blasts with temps into the mid-teens or lower.

It wintered easily in its pot spending most of it outside under roof. I ‘chunked’ it out roughly, not attempting to include much of a rootball the soil being loose anyway. It had to be supported to keep it stable and minimize damage to roots. I brought it into the basement a couple times when lows were predicted to drop below 30ºF. It did fine giving it a considerable head-start over a new plant when I planted it out in April with its two 3′ stems. I did not cut it back at replanting, but did support it with bamboo stakes until it could get its supportive roots back out into the soil. Our spring temperatures were average for us, mild, with no freezing and, again drier than normal, April receiving less than 1/3 of our normal 2.73″. It re-established and has since grown to about 5′ wide and just under that in height to this date, with multiple stems and large fuzzy leaves clothing it to the ground. I’ll be keeping my eye on the long range forecast with the intent of leaving it out all next winter, barring arctic blasts with temps into the mid-teens or lower.

As insurance I’ve taken a few cuttings, 3 in late June, 3 in earlier July, stuck them in pots with 3 parts pumice and one part my usual Black Gold potting soil, dipping them quickly in hormone and kept them under plastic in my lit, cool, basement…all have begun rooting and are pushing some new growth. I’ve removed the plastic cover as I am concerned about fungal growth. All seems well so far. At some point, with more root growth, I’ll separate them and pot them into a regular mix.

Addendum, July 29, 2022, On pollination

I was asked recently whether the flowers of Roldana petasitis, sometimes called ‘Velvet Groundsel’, are self-pollinating or at least capable of it. I don’t know for sure, but… I posted an article on this species a little over 3 years ago, and didn’t find anything specifically on this. I suppose, short of an extensive survey of these across their range, under differing conditions, the ‘easy’ way to determine this would be to grow a bunch of individuals plants widely separated and then assess their performances. One of course can always speculate, but even that requires considerable structural knowledge of the plant’s flowers, the timing of its flowering and how it is related to other allied species. I’ve only grown the subspecies cristobalensis, the form with purplish leaf undersides and stems. I’ve never bothered to notice or attempt to harvest seed from my own plants and determine their viability. The plant is easy from cuttings.

Roldana was only recently removed from Senecio, a genus of over 2,000 species in the Aster family (which includes over 24,000 species), with its distinctive basic inflorescence structure, a central disk or ‘capitulum’, generally covered in tiny disk florets surrounded with a ring of ray florets or simple variations of this. I’ve seen where some have written that such inflorescences which lack the outer ring of ray florets are more likely to self-pollinated, but this claim was unsubstantiated . Authors speculated that those with ray flowers were more attractive to bees and flying pollinators. Some ‘discoid’ Senecio spp. which had variants with ray flowers, were about a third again as often to be insect pollinated as those without ray florets. Flower and inflorescence morphology are not the sole determining factor. While certain structural traits may suggest how a flower is pollinated there are too many other factors in effect that may support other strategies.

Ray florets tend to be female, pistillate or sterile. The central disk flowers are perfect, containing both sexes and are where the production of seed takes place. Most members of the Aster family are insect pollinated. In some species of the wider family the disk florets may be ‘ligulate’ having what appears to be a single small petal arising from it, like the Common Dandelion. Disk and ligulate florets contain a nectary which release the nectar pollinators are in search of. My sense of smell is poor, but authors have written that the flowers of Roldana spp. have a sweet honey like scent, which serves as an attractant. The opening of the individual florets proceed from the ‘outside’ of the capitulum, spiraling into its center, each inflorescence cycling through the process, overlapping with others on the same plant and nearby. This process can occur over many days. Most of the species in the Aster family are protandrous, the male stamen and its anthers maturing as a floret opens on the first day, the female stigma maturing/opening on the second as it then rises above its neighboring stamen. This ‘delay’ tends to reduce the incidence of selfing.

“In subfamily Asteroideae, which comprises the majority of species of Asteraceae, including Roldana, pollen is released from anthers positioned near the apex of the corolla tube above the style, and as the style elongates, pollen is pushed out of the floret by sterile hairs at the end of the closed and unreceptive bifid stigma. [As time passes without pollen germinating on a stigma, the style continues elongating, making selfing, less likely and insect pollination more likely.] The stigma then opens and is receptive to pollination at which point self-pollen may fall on its receptive surface, be picked up by a pollinator, be blown away or fall from the stigma on to other parts of the capitulum.Pollen can be received from either florets on the same disk or capitulum, inflorescence or from that of a neighbor.

In self-incompatible Asteraceae, self-pollen fails to germinate on stigmas of the same plant, but its deposition can cause pollen or stigma clogging, thus reducing access of cross-pollen to stigma surfaces and the likelihood of a floret to set seed. In contrast, in self-compatible species, self-pollen is expected to germinate rapidly on the stigma in the same floret, or a neighbouring floret, and lead to rapid self-fertilisation and prevention of outcrossing, although as far as we know this has never been investigated in detail in any self-compatible Asteraceae.”

[From, https://www.tandfonline.com/doi/full/10.1080/17550874.2016.1244576%5D

Successful pollination, whether selfing or out crossing requires 1-10 pollen grains being deposited on a given stigma. Lower rates result in poorer fertilization. A stigma recognizes appropriate pollen via its geometry or ‘fit’. The wrong pollen will not germinate on the wrong stigma. It cannot successfully germinate and grow a pollen tube down into the ovary to fertilize the ovum. There is a genetic compatibility element at work here.

The capacity to ‘self’ across the family varies widely and can even vary between variants of the same species. So, does Roldana self? I don’t know.

Two sources:

This one describes in some detail the ‘sister’ species, Roldana lobata which is helpful in understanding petasitis. https://www.backyardnature.net/mexnat/slp/roldana.htm

The second is a broader look at the Aster family and its several distinctive morphological groups, https://cronodon.com/BioTech/asteraceae.html

Is Roldana petasitis selfpollinating ?

LikeLike

I looked into this a little more….

I was asked recently whether the flowers of Roldana petasitis, sometimes called ‘Velvet Groundsel’, is self-pollinating or at least capable of it. I don’t know for sure, but… I posted an article on this species a little over 3 years ago, but didn’t find anything specifically on this. I suppose, short of an extensive survey of these across their range, under differing conditions, the ‘easy’ way to determine this would be to grow a bunch of individuals plants widely separated and then assess their performances. One of course can always speculate, but even that requires considerable structural knowledge of the plant’s flowers, the timing of its flowering and how it is related to other allied species. I’ve only grown the subspecies cristobalensis, the form with purplish leaf undersides and stems. I’ve never bothered to notice or attempt to harvest seed from my own plants and determine their viability. The plant is easy from cuttings.

Roldana was only recently removed from Senecio, a genus of over 2,000 species in the Aster family (which includes over 23,000 species), with its distinctive basic inflorescence structure, a central disk or ‘capitulum’, generally covered in tiny disk florets surrounded with a ring of ray florets or simple variations of this. I’ve seen where some have written that such inflorescences which lack the outer ring of ray florets are more likely self-pollinated, but this claim was unsubstantiated. Flower and inflorescence morphology are not the sole determining factor. While certain structural traits may suggest how a flower is pollinated there are too many other factors in effect that may support other strategies.

Ray florets are ‘perfect’/hermaphroditic, each containing the flower parts of both sexes, but are usually sterile. The central disk flowers are also perfect and is where the production of seed takes place. Most members of the Aster family are insect pollinated. In some species of the wider family the disk florets may be ‘ligulate’ having what appears to be a single small petal arising from it, like the Common Dandelion. Regardless of their outer structure disk florets contain a nectary which release the nectar pollinators are in search of. My sense of smell is poor, but authors have written that the flowers of Roldana spp. have a sweet honey like scent, which serves as an attractant. The opening of the individual florets proceeds from the ‘outside’ of the capitulum, spiraling into its center, each inflorescence cycling through the process, overlapping with others on the same plant and nearby. This process can occur over many days. Most of these species are protandrous, the male stamen and its anthers maturing as a floret opens on the first day, the female stigma maturing/opening on the second as it then rises above its neighboring stamen. Pollen can be received from either florets on the same disk or capitulum, inflorescence or from that of a neighbor and I would suppose that would be just as accepted were it to arrive on a breeze.

Because the inflorescences of Asteraceae are so compact and numerous their production is at high rate and viable seed is assured. Out crossing, being pollinated and fertilized by the flowers of other individual plants, would seem very possible, but not necessary for the production of viable seed. Then again, I have not seen this stated by any authoritative source.

Two sources:

This one describes in some detail the ‘sister’ species, Roldana lobata which is helpful in understanding petasitis. https://www.backyardnature.net/mexnat/slp/roldana.htm

The second is a broader look at the Aster family and its several distinctive morphological groups, https://cronodon.com/BioTech/asteraceae.html

LikeLike

Hey Lance, I’ve been looking for this plant all over last few months since I first saw it in Jimi’s book!

Annie’s, San Marcos, Cistus all discontinued and even though I found some seed from the UK it’s not looking good on the germination!

Where did you get yours? Any chance you want to share a cutting from Portland to NYC to an overly ambitious young gardener who’s clearly getting waaaaayy carried away on plants!

thanks for the great blog and hope Portland Spring is feeling extra special this year!

Jamie

LikeLike

I got mine from Cistus. I wonder if because the cutting wood is so fat and the internodes relatively long, that mail ordering these in small pots may be difficult. They are fairly easy to root…I’ve done it. I’m not sure how well cutting wood would survive an across continent trip. You definitely wouldn’t want it to get stuck on a truck somewhere. I have two starts currently in 1 gal pots.

LikeLike

William, a friend who is a propagator at Cistus said that they don’t have a current ‘crop’ coming on, but they should….So, if you’re patient….These root fairly quickly. She also had doubts about sending cutting wood across country and it retaining viability….Cistus has a staggering array of stock plants in its houses, some 20,000+ I believe. This is a plant I’ve seen on site for sale many times there. You might send them a request….

LikeLike