This first installment is more general, addressing plate tectonics and the various forces and processes active in the Pacific Northwest. As a horticulturist with a strong interest in the biological sciences I also make an attempt to link the two. Biology and geology are inseparable. While geology is largely determinative, at a microscale biology has a direct effect on soils and the micro-climate. Geology is the overall, and changing structure, while biology is the ‘living’ surface, the interface between the mineral and the thin, living ‘skin’ between earth and space. The following two installments will look more specifically into the local and regional geologic forces in play. The third installment will be the most focused on the Canyon and our immediate locale.

Story is essential to the process of our understanding, it is the linking of the bits of memory together into a coherent whole, how we can share it with others and confirm or restructure it, otherwise it’s just data bits, useless in a social context and confusing to our understanding. Without story we are reduced to being merely reactive, unable to share/communicate, perceiving then reacting in the moment. Even without a group to share it with, story allows us to remember, learn, plan and act. Without it we live out of relationship, like bumper cars across the landscape. To move beyond this we must be engaged with our place. In relationship. Sharing a story with the place and organisms with which we occupy it. Language provides us with the tools to do this or simply to examine it in our heads. How do you tell the story of a place? Not the human ‘his-story’ but that of the physical land, on and with which, it occurs. We tend to think of the land on which we live as a stage, fixed, static, that this place, has ‘always’ been this way. But that is far from the truth and Oregon, the Pacific Northwest, is the geologically ‘youngest’ region of the North American continent. It has a particularly dynamic story…one that is ongoing, proceeding at a pace largely below our notice, unless we do a deep dive into its past.

I began this with the idea of telling Dry Canyon’s story, of its formation, what ended the flow of its actor/river and its following ‘senescence’, but as I began to delve into it I discovered that this was just a piece of its story, a single chapter, which left out of context, would leave a reader in much the same state, a story without necessary context. Story’s are human creations we tell to explain or understand. The thing itself, the event, has no need for it, but we do if we have any hope off understanding how things fit together and what it is is meant when we say here and now. Because the story is not over. It is still in midstream, continuously on its way to the next page, the next stage or event, never complete. We tend to think of ourselves as a kind of perpetual final, although endless, chapter with just more of the same to follow. That is more indicative of us as limited humans than it is of this place itself. This, however, isn’t our story, it is geology’s, a story of this place which is in continuous change, a state of continuously ‘becoming’, without ultimate end. Heraclitus, a Greek philosopher born in 544 B.C., once wrote, “No man ever steps in the same river twice, for it’s not the same river and he’s not the same man.” Change is one of the dominant characteristics of life and this world. We, like the river, are both ‘alive’, dynamic, changing over time, with both beginning and end, in a continuous state of change. To understand a river, this canyon, the earth itself or ourselves, we must understand the dynamic and changing nature of everything. Only then can we begin to understand our place and purpose in this world.

The adjacent map diagrams the observable geologic or mineral surface of earth around Redmond and its surrounding area. It is an Interactive Geologic Map of Oregon,. The different colors correspond to different formative events in the region’s thousands and millions of year history. The darker ‘maize’ color, the volcanic flows of the ‘recent’ Newberry complex, spreading broadly on top of the darker brown areas demarcating flows of the 5+ million year old Deschutes Formation, which tightly ‘frame’ the narrow canyon trending north in the western quarter,The story goes far deeper, literally, than this map, as you examine the many layers, descending through the strata like a book’s pages. You must pick your starting date/place. Its ultimate beginning goes all of the way back to the beginning of Earth 4.5 billion years ago. To literally stand right where I’m sitting to write these words, 100 million years ago, would have you suspended in air 3,000’ feet above the ocean, but going back to the earth’s beginning there were no oceans. No water at all and the Earth’s surface crust was in a very formative stage, its unstable surface cracked and heaved, its hardening outermost layer no doubt lifted high into its toxic atmosphere, a time when even oxygen was yet to be created from the wearing of rock and chemical break down of its components through the magic of photosynthesis and other early chemical and metabolic processes. We can never know exactly what that was like. So here, I’m beginning a mere 70 million years ago (Ma). Even then if you could precisely locate yourself, you would be without landmarks, the continental shelf on the west side of the North American continent, nowhere to be seen, too far in the distance to the east and north, over 1,100 miles away.

The adjacent map diagrams the observable geologic or mineral surface of earth around Redmond and its surrounding area. It is an Interactive Geologic Map of Oregon,. The different colors correspond to different formative events in the region’s thousands and millions of year history. The darker ‘maize’ color, the volcanic flows of the ‘recent’ Newberry complex, spreading broadly on top of the darker brown areas demarcating flows of the 5+ million year old Deschutes Formation, which tightly ‘frame’ the narrow canyon trending north in the western quarter,The story goes far deeper, literally, than this map, as you examine the many layers, descending through the strata like a book’s pages. You must pick your starting date/place. Its ultimate beginning goes all of the way back to the beginning of Earth 4.5 billion years ago. To literally stand right where I’m sitting to write these words, 100 million years ago, would have you suspended in air 3,000’ feet above the ocean, but going back to the earth’s beginning there were no oceans. No water at all and the Earth’s surface crust was in a very formative stage, its unstable surface cracked and heaved, its hardening outermost layer no doubt lifted high into its toxic atmosphere, a time when even oxygen was yet to be created from the wearing of rock and chemical break down of its components through the magic of photosynthesis and other early chemical and metabolic processes. We can never know exactly what that was like. So here, I’m beginning a mere 70 million years ago (Ma). Even then if you could precisely locate yourself, you would be without landmarks, the continental shelf on the west side of the North American continent, nowhere to be seen, too far in the distance to the east and north, over 1,100 miles away.

The map is interactive and produced by the State of Oregon. It is the most up to date geological map of our state. You could examine it for hours and if you are truly interested, you will develop a better understanding of the geological details of this place and its origins, but you will also have to do a lot of research into what exactly these differently colored areas represent. Those like the dark brown Deschutes Formation included hundreds of smaller events, geologists have put together to aid understanding. Others on the map are more singular, but can still be broken down into more discrete parts. Where those shown here came from and when, and what preceded them, isn’t shown here. They are buried beneath.The map shows the surface. It overlays and disguises all that came before…and there was a whole lot of that. You will need to develop your understanding of the nearly countless formative events and the descriptive jargon geologists use, because without it, it’s all just ‘rock’, passive landmarks, its seemingly irregular ‘pages’ overlaying older ones, each such ‘page’ written, derived from a unique source, usually incomplete having been subjected to erosion. Any landform here is the ‘result’ of continuing formative and erosive processes. One needs patience and an inquisitive eye to ‘see’ it.

[Before I go any further, let me remind you that I am a horticulturist, not a geologist nor a volcanologist. This is me learning and this is an incredibly technical and layered topic, so forgive me my errors. I am no ‘expert”. When doing my research i’ve found that even the ‘experts’ are not always in agreement and what is generally accepted changes over time as the ‘story’ is built out. This is a pattern repeated throughout the physical and biological sciences. The complexity of geological history, extending literally billions of years, can ensnare anyone. The details are fascinating, but their interpretation is subject to error and correction. To fault geologists and science for these formative errors is unfair. We all make them. It is upon us to examine and weigh their words for ourselves. Disregarding their interpretation out of hand does no one any good. Part of my intent here is to awaken the reader, their curiosity, their sense of wonder and awe, to humble ‘them’. This world is far more complex and beautiful than our economics and politics pretend. As we continue our forgetting of this, our mistakes accumulate and our world becomes ever more fragile. Nature will survive, but will we?}

Plate Tectonics and Earth’s Evolving Surface Crust

The chapter describing Redmond’s Dry Canyon ‘story’ is recent, geologically speaking, carved out of a piece of the larger regional story, of an ongoing tectonic ‘car crash’ of ‘plates’, many millions of years in the making. North America is ‘driving’ south-westerly, slowly and inexorably, away from a still expanding Atlantic Ocean, its massive and dense base rock, its pluton, riding atop the earth’s hot, dense, mantle, colliding with the much ‘younger’, less massive and dense crustal plates still arising from beneath the Pacific Ocean. The earlier Kula Plate, ‘speeding’ along north and east at some 4” per year. was entirely subducted beneath the slowly southerly and westerly moving North American plate, which is plodding along at about 1” per year. The Pacific Plate follows in Kula’s path, the Juan de Fuca plate, a relatively small chunk of it, is currently diving beneath North America along the Cascadia Subduction Zone off the coast of Oregon, Washington and the northern end of California. This is not, however, the only point of ‘collision’, it continues north and south along the entire length of North and South America.

The Earth is in constant internal and surface motion, of geological ‘birthing’ and ‘consuming’ of its crustal surface. The plunging rock of the Juan de Fuca continues to be pinched and crushed between the Earth’s inner mantle and the North American pluton. The mantle itself is heated to temperatures of several thousands of degrees because of the pressure produced by gravity crushing the dynamic crust, 9 to 12 miles thick, into the mantle under incredible pressure, the heat moving outward continuously, conducted directly through its mass, before radiating it off to ‘space’, slowly moving the materials in and around its mantle in the process, the hotter, less dense, rising surface ward. The crust exists as many plates being forced into never ending motion, each with their own momentum, direction and speed new crust arising from deep fissures in the oceans from which magma arises. The colliding tectonic plates, form, drift and subside at a pace far too slow for anyone of us to casually observe, while new crust forms continuously driving plate movement, supplying the ‘material’ that will later erupt through weak spots lifting the landscape, forming mountains and adding successive layers to the region’s surface. Spreading. The crustal plates possess incredible momentum akin to massive ships on the sea.

In some areas portions of the crust buckle, mountains heaving up, basins sinking, gigantic rifts opening slowly tearing the crust apart, the plates moving along fractures, faults, in the crust, themselves disguised by the surface above. Volcanoes, vents and fissures are associated with these faults, issuing lavas and other materials on to the surface. Sometimes fluid, the resultant lavas flow across the surface, their speed and thickness, dependent upon temperature, viscosity, chemical composition and slope. Pyroclastic ash flows of hot volcanic gases and particles ejected explosively, flowing across the surface at speeds of up to 400+ mph, with temperatures of 1,800ºF incinerating everything in their path. Lahars, volcanic induced mud and debris flows bury everything in their path. Ash falls, explosive events which often occur at the end of a vent’s effective life, in others early, are explosive ejections of scoria/cinders or pumice with their high silica content. All this adds to the thickness of the crustal surface, while the slow work of erosion tears it all down, sediments, blown and washed away, filling basins and low areas. Layer after layer the landscape thickens, thins and is transformed, rising where pressures beneath increase, sinking in others beneath its massive increases, faulting, tilting where forces stretch it thinner. The heat and pressure transform rock from one form to another. Crystals form in the molten material as it cools, larger where its slowest, absent where the cooling is rapid. ‘Seams’ of minerals form in the intervening spaces chemically changed by the pressure, heat, water and acids in their own process of escaping from their crustal traps, collecting, coalescing in purer form. Entire landscapes transforming, being torn apart forming deep rifts into the crust, buried geologically rapidly or over millennia by erosion and sedimentation. This complex combination of forces locally has translated into the formation of the Deschutes Basin with its shifting rivers and streams, its complex layering resulting in the flow of groundwater far beneath the surface as if finds its way moving slowly easterly and northerly from the much wetter Cascades, down through more porous layers sandwiched between those that are more dense, the life giving water upon which we depend on in this now desert, hidden, trapped below the surface until we tap it or it emerges from seeps and springs.

All of the continents are in a similar continual state of flux, their seemingly fixed rigid surfaces constantly changing relative position, building and fracturing in response, eroding and flowing to the oceans, filling basins. The Atlantic Ocean continues to widen pushing North America westerly. Africa, India, South America and Australia are still moving north, independently, away from their former collective partner, Antarctica, all once part of the super continent, Gondwanaland…(but that was 200 million years ago). South of us California continues sliding and rotating northward along the San Andreas Fault colliding with the PNW causing the southwesterly portion of it to rotate clockwise, rending the landscape. The Pacific and Juan de Fuca plates moving north and eastward, pushed by massive forces arising from the Pacific Rift Zone, the Pacific Plate still expanding, sliding beneath the North American Plate. The Pacific Northwest contains the youngest rock and landscapes of North America and it is no where near ‘finished’.

The seemingly solid surface of the Earth is not fixed at all. It ‘slides’ across the inner mantle, different ‘sections’ in different directions. The spinning mass of Earth creates our ‘days’, stabilizing the ‘core’ on its axis while the surface crust shifts. An inch may seem minimal for a year’s movement, but over a million years the North American Plate has moved 15.8 miles to the south and west, while the system of Pacific Plates has moved 62.4 miles north and east. Over the course of geologic time these distances are truly incredible moving 100 times that over the last 100 million years, 6,240 miles in a period over which Oregon and the West formed. This crustal movement has resulted in the buildup of the West coast, crust subducted, while portions of islands and ocean floor were folded and heaved up, accreted, to the edge of the North American Plate, the Blue and Wallowa Mountains containing rock of marine tropical origin and fossils of the ancient sea bed.

100 million years ago, at this particular latitude and longitude on which we live, if we could be here, we would be ‘hanging out’ 3,000’ above the Pacific, dry land having not yet ‘arrived’. The North American continental coastline was far to the east defined roughly by the Idaho border its ‘edge’ a complex mass of folded and broken strata, underlain by the North American pluton, topped in places by younger volcanic rock, itself eroding in a never ending dance. Hell’s Canyon marks the edge of this activity zone. An archipelago, a collection of islands, was moving from their tropical oceanic point of origin far to the west and south, comprised of different and uniquely identifiable rock, to be scraped off millions of years later, and added to the North American coast line, accreted and later ‘welded’, through volcanic activity, into the present day whole. Today’s west coast, from Alaska to Mexico, was accreted, or the result of volcanic action derived from the subducting tectonic plates.

This schematic is from the National Park Service and gives you a graphic overview of the process. Check out their site discussing the Cascadia Subduction Zone and volcanism.

These processes and forces are acting continuously around the world. Crustal plates are all in motion moving independently according to the particular forces exerted on them, each with its own momentum, as the Earth’s ‘solid’ crust shifts and tears, in some cases opening up giant ‘rifts’, often hidden by the resultant sedimentation of the eroding and rising framing ‘halves’, while at other tectonic collision zones, mountain ranges, such as the Andes, Himalayas and Alps continue to rise. In other cases, where plates are sliding alongside one another, the movement is largely unnoticed but for the sudden slips which create earthquakes and the resulting discontinuities of misaligned strata, streams and other features. Sometimes the resultant ‘collisions’ cause rotations of colliding terranes, the examination of which reveals a crazy quilt of broken and mixed rock of different origin, hidden fractures and fault lines below the surface.

In Central Oregon, these systems of faults converge in the Brother’s Fault Zone, a western trending band between northern sliding California, the stretching and thinning Basin and Range country of Nevada, at its intersection with the dense, base rock of the Blue Mountain region to its north. The Brothers Fault Zone intersects with the Cascades, and the associated northerly trending Sisters Fault Zone, increasing the incidence of geologic ‘volatility’, birthing volcanic action. Central Oregon lies at the center, the pivot point of these regional forces, the colliding Pacific Plate pushing all of it, holding it together, mitigating those forces that might otherwise tear the Pacific Northwest apart. Geologists understand this. By living where we do it is simply a matter of time before other massive geological events reshape the region’s surface.

Geologists call the additions of relatively intact plate, ‘peeled’ back by the leading edge of the westerly ‘growing’ continental plate, terranes which are accreted to the continent. They ‘pile up’ on the surface at the impact zone of the two plates, the remaining portion plunging down below the extending crust above the mantle. These terranes have collectively ‘built’ much of the base rock that underlies Oregon, Washington, British Columbia and California. Much of this has subsequently been ‘buried’ beneath volcanic and sedimentary layers over time effectively gluing or welding them into a whole, although one still subject to movement. Some of these terranes were actual islands, that once formed an archipelago within a shallow sea off the former North American coastline. Island by island, terrane by terrane, they added their material to the extending continent, massing ahead of the advancing North American Plate, its continent wide pluton base acting somewhat like a ‘dozer’ blade buckling a heaving Pacific Plate, forcing the terranes above or below into the ‘cauldron’ of Earth’s mantle. This shallow sea then built up with terranes, volcanic editions and the eroding sediments filling a basin which kept ‘filling’ the intervening space slowly rising between the Blues and the formative Cascades to its west.

The most notable visible terranes of Oregon today are the Wallowa and Blue Mountains in Eastern Oregon with their unique and identifiable base material. Other examples a little further afield include Washington’s North Cascades and the Siletz terrane which accounts for much of the base rock of Oregon west of the present day Cascades. The entire west coast of North America is ‘built’ atop accreted ‘terranes’. The successive volcanic events again acting to ‘weld’ these together as well as build upon them. This molten material, magma, is formed from that portion that plunged below melting and transforming in the process. While this was going on, and continues, the forces of erosion relentlessly wear these ‘new’ forms down.

Like crustal expansion and mountain building, erosion too is unrelenting, constantly wearing down what these forces build up. One does not happen first, and once ‘completed’, yield to the other. They are geologic ‘dance partners’. In some of the Northwest region the erosion has worn away most of the volcanic layers leaving these old accreted islands, rock, above the surrounding grade. In others these terranes have been buried beneath the sediments worn and carried away by erosive forces from higher ground. ‘Here’ then, is not the same ‘here’ now, in any sense. In Oregon’s eastern canyon lands broad, flat topped highlands and rims stretch on for miles still being eroded methodically by the ‘simple’ freeze and thaw cycle, the flow of rivers and streams even the by the wind which wields its tiny sediment chisels, the young ‘caps’ tumbling down as they are undercut, old and young rock tumbled and mixed, then carried by the rivers and deposited in a melange downstream. The crust of the Earth has grown and moved across its surface relative to the axis, stretching, cracking, heaving, eroding in a continuous process, barely imaginable.

While geologists attempt to understand all of this, studying local features and regional broader patterns and periods, the shear scale of time, the nearly infinite number of variables in play, the depths beneath which the physical record of much of this lies, the ‘puzzle’ that is Oregon and the West Coast…understanding it, becomes an even more daunting endeavor. The formation of a mountain can take many thousands, even millions, of years. Erosion itself leads to the building up of the landscape through infilling of basins, the formation of broad deltas and sometimes through singular or cyclic catastrophic events like the Missoula Floods of the last glacial period of the Quaternary Ice Age, which occurred cyclicly over a period 13,000 to 15,000 years ago ‘sculpting’ much of eastern Washington, carving out the Columbia River Gorge while depositing rich soils across the Willamette Valley in its aftermath.

Definitive dates assigned to such ‘processes’ are misleading. Geological features are ongoing. We are limited and biased in our view of the physical Earth, as solid and fixed by our uniquely human perspective, our relatively ‘short’ lifespans and the great difficulty of understanding that which is so much greater than ourselves. Explosive eruptions and earthquakes are only a piece of this and one of few geological events we can experience and comprehend in our life times. Even then periodic, and massively transformative earthquakes, like those associated with the Cascadia Subduction Zone, escaped our, white settler people’s, awareness (although native peoples certainly experienced them and have passed the stories along over generations, stories generally ignored by we European newcomers.) until about 40 years ago when the evidence was finally recognized and understood for what it was. The existence of the Crooked River Caldera, one of the largest such natural structures on Earth, went unnoticed until 2003, ‘hidden’ by nearly 40 million years of erosion, volcanic activity and the continuous infilling of sedimentation, all obscuring it. Even in this, ‘singular’ volcanic events are themselves part of larger ongoing events. The volcano ‘destroyed’ in the collapse which created the Crooked River Caldera was itself a part of the larger Ochoco Volcanic Complex which was a part of the larger John Day Formation which itself overlaps with the older Clarno Formation, stretching back 44 million years. We draw lines to separate these into individual, more comprehensible, and linear, events, but in so doing simplify the history we tell each other in ways that miss the nuanced and overlapping unfolding of all of this. Again, going back to Heraclitus, the process is ongoing, without finish. Because we have difficulty understanding it, doesn’t mean it didn’t or couldn’t happen. Happy endings, endings of any kind, are a product of human desire. We ‘modern’ people have trouble with ‘simply’ being, with dynamic, ongoing process. We seek purpose in the short term while ‘purpose’ lies within relationship, within the recognition of one’s role, whoever or whatever that might be. We, like the landscapes we live within, are a part of a much larger whole, not ends in ourselves.

All of this goes on continuously, generally incrementally, beneath our notice…. We like to define events as discrete, bounded, but geology ebbs and flows. It is never ‘finished’. An individual eruption may indeed be sudden and explosive and may be preceded by a many thousands of years building process from dozens or even hundreds of minor eruptions that both blast and build, sometimes producing flows which bury others that serve to ‘weld’ the looser ‘fall’ of earlier explosive eruptions together. The landscape, measured at any given moment, is literally layered, each identifiable, if one knows how and has the tools to read it, buried below those which followed. All of this regionally defining geology took place many thousands and millions of years before our time, and in some cases, before even any mammalian species existed here. These processes of building, wearing and change continue and shall far into the future.

The Complications of Time

A million years, is incomprehensible to a person. From a geological perspective it is but a few moments. The earth is estimated to be 4.5 BILLION years old. A billion is a thousand million years. How long is that? If you could compress a million years into a single, long, 100 year, human lifetime, every minute that passes for you would be the equivalent of 7 earth days. A year would pass in just over 52 minutes. One hundred years in 5,214 minutes, or 3 days, 14 hrs and 54 minutes. A thousand years in 52,140 minutes or 36 + days. Think of standing in on!e place watching for those 36 days, a month plus, while watching a thousand years of changes around you…and that is still a fraction, only a thousandth of a million years.

Think of watching a movie. Movie film moves at 24 frames per second (fps). In one minute 7 days would have passed. In one second, 2hrs. and 48mins. would pass. At 24 fps each frame would be a picture taken 7 minutes later. To watch such a film would be incomprehensible. Life would occur at a blur. The Earth itself would appear to be animate, while the organisms, the animals anyway, which populate it, almost invisible, living at a speed which our changed perspective blurs. Individual animals would blink in and out of existence, visible only when the were still, sleeping or hibernating. We live at too high a rate of speed. Our time scale is a human abstraction. To understand we must ‘stitch’ the lives and memories of countless generations before us. To understand what is coming we must try to imagine the lives of generations to come. We have not been very good at this. Without a great deal of care and focus we miss so much of what is going on around us.

Back to colliding tectonic plates and accreted terranes. The colliding plates, the subsidence of the Juan de Fuca Plate along the long edge we now recognize as the Cascadia Subduction Zone, plunges beneath the North American Plate adding its own material to the leading edge of the North American Plate. As the plate sinks into the mantle, it gets compressed more and more tightly by the pressure of the overlying crust. Water comes along with it. This pressure builds, ‘squeezing’ the water, H2O, Hydrogen and Oxygen, out of the rocks that make up the plate, heating it as it plunges deeper and deeper. Heat and pressure are transformative. The ‘rock’ changes chemically, lowering its melting point, allowing Earth’s heat to melt it. The melted rock, the magma, is less dense than the surrounding rock, and rises, sometimes lifting the crust above it, sometimes so slowly that it cools and hardens below the surface, forming incredibly dense rock, other times forcing its way to the surface through faults and fractures, forming volcanoes, issuing out from cracks and ‘vents’, weak spots, periodically spewing out, thickening the crust, as lava flows, violent pyroclastic events or melting overtopping ice and snow, forming fast moving lahars and burying everything in their path beneath rock, mud and trees. Sometimes the magma, rises through groundwater, super heats it, producing powerful explosive forces which result in ‘violent’ ejections of massive amounts of material leaving behind a maar, a broad shallow crater. (Think of ‘Hole in the Ground’, a maar, which formed when magma came up through the crust in the broad paleo-Lake Fort Rock.) All of this has collectively formed a landscape several thousand feet thick in Oregon.

Early on, a shallow, tropical sea covered much of what was the broad band of Central Oregon stretching north and south. This was the situation up into the latter part of the Cretaceous Period, 70 million years ago. Before this there was little to no volcanic activity here. In 2003, paleontologists discovered part of a large skull in Cretaceous rocks near present day Mitchell, Oregon. It belonged to a Plesiosaur – a 25 foot long marine reptile that lived during the Age of Dinosaurs, about 80 to 90 million years ago. Mitchell today rides above on that uplifted terrane which was once sea floor. Its elevation 2,770’. There are otherwise no fossil remains of dinosaurs in Oregon, largely because Oregon was an archipelago of scattered islands with no significant land mass for dinosaurs to occupy. North American dinosaurs were found in the much older rock east of the Rocky Mountains in places like Dinosaur National Monument on the flank of the Uinta Mountains at the border of Utah and Colorado where the land is much older.

Setting the Physical Stage for Life

It is the physical, abiotic, features, the landforms and those features which shape and determine them, which set the stage for life, which in turn affect those same characteristics through an endless system of complex relationships, effective positive and negative feedback loops. Positive, because through their actions something is increased, or negative because something is diminished by the increase of another, while others are unaffected…at least directly. In this way life supports life as a process. Individuals are thus supported, the system overall affected, their role expended, the system ‘regulated’, in a kind of global homeostasis. With the death of the individual, its component parts are broken down, conserved, recycled, and the next individual created to serve the larger self regulating system. The physical conditions set the initial stage. Life, in colonizing its niches, modifying them, creating opportunities for more, increasing complexity while adding dynamism and stability to the entire system. Volatility is then minimized so that the overall system remains within ‘healthy’ margins.

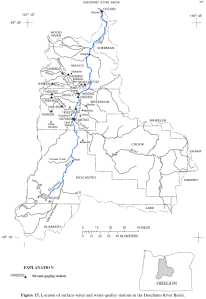

The narrow finger pointing north is the Descchutes River’s low point, where it enters the Columbia. The western edge follows the crest of Oregon’s Cascade Range, everything west of that ‘line’ draining itnto the Willamette. To the east lie the high plateaus and Blue mountains which drain into the John Day River, north to the Columbia or east into the Snake and then into the Columbia. To the south the high countr drains away into the Great Basin of the Intermountain West, a basin with no outlet to the Pacific, where precipitaition remains, going to support life there or lost to evaporation.

This is the Deschutes River Basin.

Central Oregon is a political designation, a man imposed definition of the area, which commonly, at least over here, refers to the tri-county area of Crook, Deschutes and Jefferson counties, purely arbitrary areas. Were we more interested in definitions that recognized the place itself there are several other definitions that would better serve, such as the Deschutes River Basin as a whole or that which we could further divide into its several parts, dependent on how finely you want to divide the place such as into the upper or lower basin, or into basins defined by the watersheds of its contributing streams, the Crooked, the Metolius or its many creeks or streams like the Tumalo and Whychus. Of course you could go the opposite ‘direction’ and join the Deschutes River Basin to the larger Columbia’s, that would also be ‘correct, but be far less ‘local’, moving away from my overall purpose here of defining this particular local region and the conditions for life, this place presents.

Or, you could divide the region based on eco-region, those related plant communities that colonize a place. Doing this places ‘us’ in the sprawling Blue Mountain Ecoregion which stretches east and north to the Snake River, but it also eliminates much of what lays near by and goes to physically and aesthetically defining our experience here.

Organism live where they can, where conditions are supportive. In doing this they effect the conditions for themselves and other organisms, as well as affecting the physical conditions themselves. How? Through the formation of soils, their production of organic acids which not only decompose other organic matter, but work to release minerals from the rock itself which they require, They also, through their collective existence, moderate local temperature and humidity, play a role in precipitation patterns and in shaping and guiding winds. Through their tissues, their growth and death, they retain and release nutrients that would otherwise be lost and the community with them. They help determine the physical structure of soil, effectively ‘gluing’ particles together into ‘crumbs’, improving a soil’s ‘friability’, improving its drainage and aeration and its ability to serve a plant’s needs, in addition to drawing water back up through the soil which would otherwise be lost. They do this in cooperation with other soil organisms, with which they have both free and more direct, mutually beneficial relationships, including those with bacteria and fungi. They support and augment many chemical processes at work in the erosion of soil and the formation of protective crusts, often extending far beneath its thin surface, as well as an essential role in the formation and maintenance of the atmosphere itself, its composition and removal/recycling of pollutants back into useable, more benign component ‘parts’. Recall that ‘nature’ wastes nothing. It converts matter from one form to another, utilizing those energies always available to it, driven ultimately by the Sun and the heat generated through the earth’s massive core and the working of gravity.

We get ourselves into trouble when we continually seek to separate and define functions, failing so often to see the interlocking, dependent relationships, without which the system functions poorly if at all. Landform, soil, water, atmosphere, living organisms, don’t exist as separate things. Each is bound to the rest via relationships, many and complex. Like geology, we tend to think of all of these ‘things’ as fixed, as givens, because they have been, more or less, through our individually limited experiences.

Life: Evolving With the Geology

Life made earth habitable for us today. Geology sets the ‘table’ and shifts the ‘furniture’ around. Life made earth habitable, preparing the way for land plants 470 million years ago. There was a time when Oxygen was locked away in mineral form. Animal life, dependent upon Oxygen for respiration couldn’t have evolved before Oxygen levels in the atmosphere reached a critical level. The earliest forms of life weren’t dependent upon it. Metabolic processes couldn’t rely on it. At the time Oxygen was in fact ‘toxic’ to organisms of the time. In a sense it still is today. Oxygen, through the process of oxidation, the chemical breaking down of compounds through their energetic combination with oxygen, either slowly within organism’s bodies or explosively through the uncontrolled process of fire, combustion, degrade organic compounds. In living organisms these must be replaced or the organism dies. This happens continuously within our bodies, but is balanced out by the opposing metabolic forces of organic complexity building, until of course, we no longer can. Plants, evolved from simpler organisms utilizing photosynthetic processes which released Oxygen as they ‘built’ carbohydrates to fuel their own growth. The proportion of Oxygen in the atmosphere increased as carbon became sequestered in long lived organisms, preserved in ‘dead’ organic materials in the ground and in the oceans. (See, “The Role of the Ocean in the Global Carbon Cyclee: how the ocean absorbs carbon dioxide”) Carbon dioxide was far more abundant in the atmosphere and the earth’s surface in the early stages of life on the planet, as a result, was significantly warmer than it is today. The earth has changed, over many millions of years and life evolved with it. Affected it. As it still does. Change happens. Life regulates it, at least it does within limits.

It is important to keep in mind that where these different ‘spheres’ come together, at and near the earth’s surface, life is most abundant. Move in any ‘direction’ toward the margins of these habitable conditions and the frequency of life, its diversity, diminishes. As one ascends up through the atmosphere it thins. Above 10,000 feet and many people start having problems. By the time one reaches 20,000′ elevation, many people can begin having serious life threatening problems. At approx. 26,000′ there is insufficient Oxygen for us to live for all but very short periods. Our blood-oxygen level drops to levels that cannot sustain the metabolic activity necessary for cellular life. At 12 miles up, were you still alive the lack of pressure would allow your blood to boil away.The frequency and diversity of life diminishes rapidly as one ascends in elevation. Even at the equator, where life is most diverse, most of life cannot adapt to long term conditions that exist at a mere 20,000′, a portion that drops even more quickly as one approaches the poles.

But let’s say that earth is livable up to 20,000′. The earth 41,870,040′ in diameter. The atmosphere is a gossamer thin layer around the earth. Life can be sustained only within it. Were our own skins of a similar proportional thickness, and we were similarly ‘ball’ shaped, about 2.5′ in diameter, a rough approximation, I know, a big if, our skin would be around 0.00119417129′ thick. About 0.014330″, .364mm. Human epidermis ranges from 45-105 cell layers thick. This equates to between 0.2 – 1.6 millimeters. It is thickest on our heels and palms. The dermis below that, is the thickest skin layer. On average, the dermis ranges anywhere from 1.5 – 4 millimeters thick. Our skin then ranges from between 1.7 to 5.6 mm thick. The habitable layer of atmosphere is equivalent to 1/3 to 1/17 of that. That thinnest layer is found on our eyelids. This is where life occurs and includes most of the weather we experience and within which all but the greatest mountains fail to penetrate. This is the province of life and all of its relationships, outside of course the sun which is the engine of almost all of it. Into this thin layer we exhaust pollutants and share all. The products and descendants of everything here now, transformed and continue to do so within this thin living layer.

A Closer Look at the ‘Big Pieces’ of Oregon East of the Cascade Crest

Accretion of the Blue Mountain Terranes –

The northeast most part of Oregon is a collection of ‘fragments’ of various islands and masses of crust, scraped off, broken, wedged together, relatively intact, folded and buckled, pushed up into ridges and mountains on edge, sometimes later overtopped by volcanic eruptions which have subsequently been eroded back down to the base rock, all of this taking millions of years, adding to the crustal mass. ‘Broken’ as these rigid layers of rock are, upended and folded, a chaotic playground of force and immovable object. This gives the observer some idea of the tremendous forces involved. Sometimes this accumulating mass is so great that it causes the ‘young’ crust to ‘sink’ down into the mantle, leaving only the topmost, youngest levels revealed. Layers get buried by later lava flows and depositions eroded sediments. Geologists study these exposures where the find them, such as along major faults, road cuts, in mines and wells or uplifts where massive blocks, many miles long, are alternately heaved and dropped like Abert Rim, Steens Mountain and the many mountain ranges of Basin and Range country. Other times they study the layers comprising the walls of canyons incised by rivers. Other areas are more gradually revealed through the relentless processes of weathering and erosion, the wearing down of mountains, leaving their older, often denser core material standing, the eroded sediments, burying lower elevations, combining to form ‘new’ sedimentary rock, again over vast periods of time, all of which are continuously overtopping older, lower layers, younger flows and deposits combining to form a complex melange.

Geologists are able to chemically analyze the rock which goes to determining where and when they were first formed. Other hints lay within the micro-structure of the rocks themselves, effected by the earth’s magnetism when it formed, before it was ‘moved’ and folded. Radiometric dating measures the amount of naturally occurring radioactive isotopes found in a particular rock, isotopes which ‘decay’ at a known rate, revealing the rock’s age.

Today these comprise the bedrock and some of the peaks and ridges of the Blue and Wallowa Mountains on into far western Idaho. Geologically, walking in the Blues and Wallowas feels other worldly, when your base understanding of Oregon’s mountains is limited to the volcanic Cascades. These are heaved up, ‘imbricated’, broken, tilted, somewhat ‘scrambled’ and driven together ancient crustal layers, like a variably sloping layer cake, the layers broken and swirled in a process still underway.

Maps like the one below right show these, puzzle pieces as colored polygons outlining the identifiable portions of accreted terranes. The intervening ‘white’ space comprised of younger volcanic material and accumulated sediments. Rock of these terranes formed as early as the Early Devonian, 410 million years ago, far out in the Pacific, long before they began colliding offshore with the North American Plate, a process which began some 220 million years ago. At that point they began their advancing and rotational ‘dance’, mixing and churning north-easterly as Nevada and its spreading/thinning crust, stretching westerly in a confusion of forces. The Baker terrane, was accreted the longest ago, much of it since overlain with heavy volcanic activity and subsequent sedimentation. The complex of Baker terranes contains rock from the ocean floor from the Middle Devonian to Late Jurassic, 375 Ma -175 Ma, rock in some cases, older than the earlier accreting Wallowa Terrane. The Olds Ferry Island Arc Terrane, to the south, contains rock from the Middle to Late Triassic. These three ‘groups’ of terranes, are ‘separate’ events and have a long history of dynamic movement, a concept hard to grasp, not just because of the time scale involved, but because of the fact that the solid rock beneath our feet continues to move and is not near so fixed as we tend to think, both lifting and sinking, shifting direction, resulting in the mixed melange of surface structures evident today.

Maps like the one below right show these, puzzle pieces as colored polygons outlining the identifiable portions of accreted terranes. The intervening ‘white’ space comprised of younger volcanic material and accumulated sediments. Rock of these terranes formed as early as the Early Devonian, 410 million years ago, far out in the Pacific, long before they began colliding offshore with the North American Plate, a process which began some 220 million years ago. At that point they began their advancing and rotational ‘dance’, mixing and churning north-easterly as Nevada and its spreading/thinning crust, stretching westerly in a confusion of forces. The Baker terrane, was accreted the longest ago, much of it since overlain with heavy volcanic activity and subsequent sedimentation. The complex of Baker terranes contains rock from the ocean floor from the Middle Devonian to Late Jurassic, 375 Ma -175 Ma, rock in some cases, older than the earlier accreting Wallowa Terrane. The Olds Ferry Island Arc Terrane, to the south, contains rock from the Middle to Late Triassic. These three ‘groups’ of terranes, are ‘separate’ events and have a long history of dynamic movement, a concept hard to grasp, not just because of the time scale involved, but because of the fact that the solid rock beneath our feet continues to move and is not near so fixed as we tend to think, both lifting and sinking, shifting direction, resulting in the mixed melange of surface structures evident today.

Blue Basin, part of the John Day Fossil Beds National Monument, a piece of one of ocean floor terranes as one travels east towrd the Blue Mountains

The Brother’s Fault Zone, contains multiple faults oriented together, to dissipate the tremendous forces generated by California’s movement and the stretching/thinning of the crust rending the Basin and Range country, resulting in the north-south faults across Nevada, deflected west where the stretching crust abuts the denser mass of the Blue Mountain region. This adds to the rotational forces in SW Oregon and northern California as they are deflected westerly. where they collide with the advancing Juan de Fuca Plate, creating a fulcrum of competing forces, pivoting against the mass of the Blue Mountains and Ochocos. These forces effectively rent and ‘sheared’ some of the Blue Mountain terranes, the separate ‘parts’ slowly separating.

This sliding, shearing and rotation, with the continuing accretion of plate material, has resulted in the formation of the Siskyou and Klamath Mountains of Northern California/Southern Oregon, which includes rock of the same accreted Blue Mountain terrane, separated and rotated clockwise, westerly. California, sliding along the San Andreas Fault northward, seems to be driving this rotation. The Great Basin region, to the south, continues to thin and separate, blocks of crust alternately tilting, rising and falling along faults, breaks in the crustal surface, forming the characteristic north south running series of 100 or more mountain ranges, (Nevada truly is the mountain state.), and their accompanying basins, that define the region. Death Valley is one such basin. Telescope Peak, at 11,049′ stands as a part of the Panamint Mountains between Death Valley with its Badwater Basin at -282′, to its east and the Panamint Valley to its west. These same faults continue into Oregon terminating below the aforementioned Brothers Fault Zone where they are bent westerly, immovable objects colliding and sliding. The formation of this region demonstrates the relative ‘fluidity’ of crust here.