We all took American history in high school, a history that ‘hit’ the ‘high’ points of our founding and development, which was cursory at best. I, at least, was taught a ‘safe’ history, which presented those ideas and events upon which most Americans generally agreed, selected by textbook editors, school board members and political leaders…in other words, a history that created no ‘waves’, nothing controversial, or that presented critiques of our common American mythology, of our ‘greatness’ and our exceptional beginnings and path to today….Omitted was everything else, although some was given incidental mention, as if that some how explained it, even though its role may have been pivotal in the formation of the world today. To ensure an adequate disinterest in pursuing our history further, which might likely result in deeper discussions and questions, we make the high school history as boring and repellent a topic that we can. We strip it down into memorizing specific dates, events, heroes and opponents, but just their occurrence without a meaningful context. No ‘story’ by which understanding might be attained. History rendered boring, off putting and largely irrelevant to our lives today. Bravo! We’ve done that. And now we suffer the consequences.

We all took American history in high school, a history that ‘hit’ the ‘high’ points of our founding and development, which was cursory at best. I, at least, was taught a ‘safe’ history, which presented those ideas and events upon which most Americans generally agreed, selected by textbook editors, school board members and political leaders…in other words, a history that created no ‘waves’, nothing controversial, or that presented critiques of our common American mythology, of our ‘greatness’ and our exceptional beginnings and path to today….Omitted was everything else, although some was given incidental mention, as if that some how explained it, even though its role may have been pivotal in the formation of the world today. To ensure an adequate disinterest in pursuing our history further, which might likely result in deeper discussions and questions, we make the high school history as boring and repellent a topic that we can. We strip it down into memorizing specific dates, events, heroes and opponents, but just their occurrence without a meaningful context. No ‘story’ by which understanding might be attained. History rendered boring, off putting and largely irrelevant to our lives today. Bravo! We’ve done that. And now we suffer the consequences.

We are today largely a population which is disinterested in our own history, incapable of understanding the forces, still in play, that beleaguer compromise, shape and limit us. But history is much more than we were taught. It is also about that which we were most zealously schooled to NOT believe, those events and people which would prompt us to question the shallow history formally presented to us in, “yawn”, history class. History as taught to us was boring, stripped down so much as to have no meaning. A list of events that support an extremely limited vision of this country’s ‘Life’. History is the ‘story’ of a selected person, people, place or thing over time. A collective, active and shared remembering of the events over time central to the selected topic. It is a story of its unfolding, its becoming, even its end. The story of one person’s life, as well as that of the many millions of people that comprise this country’s people over its founding and evolution. It is not the simple or linear story taught us as if it were complete in our high school history class. History, properly presented, is a layered and complex telling of a period and the many relationships that went into its actual unfolding. Not just an accumulation of each personal narrative, but a coherent telling of all of its many parts, stripped of distracting asides, petty differences and the self-serving biases that can so often cloud the understanding of others. In history, not everything matters. It is up to the responsible historian to utilize a degree of discernment to make the past more than a confusion of personal observations. History is not just what one person or group might claim it to be. History, requires a ’roundness’, a valuing that allows for the movement and flow of one’s subject over time. ‘What happened’ acquires weight and direction in the telling of history. Without doing this history descends into manipulation and propaganda. Omission, that reduction of events, the details of their occurrence, the weight or value of them as time progressed, down to its simplistic, boring regurgitation of names, dates and spare events, strips history of its value as a tool for understanding, rendering it instead into tool of those who would rather no one looked too close. Doing so is intentional. The ‘myth’ of our founding has become more important, more powerful, than the story of our actual founding and the events which occurred along the way. That ‘myth’ can only be maintained in the fogginess of belief. It cannot hold up under close scrutiny. History ‘flowers’ when the light of critical thought shines upon it. In doing this the proper teaching of history encourages students and citizens to ask the questions any journalism student knows to be essential to telling of any ‘story’:

- What – happened?

- Why – did the event to take place (the cause)?

- When – did it happen?

- How – did it happen?

- Where – did it take place?

- Who – are the people involved?

And then they’re all the follow up questions to insure that the ‘answers’ one has found are accurate and true. Is the record you’ve examined complete? Was your source biased in anyway? After all, one’s view of the world and its events, are shaped by ‘where’ we stand, our personal history, our biases. Given the ‘power’ a high school history curriculum has to shape a students world view, and the life to follow, this is an essential question. Who have we entrusted to produce and provide the books and the ‘stories’ they tell? What is omitted? What is denied even to be mentioned? Another story can be told by every viewer, every participant. A history then requires deep study and consideration on the part of its ‘creator’. What is excluded is every bit, and possibly even more, as important as that which is included. When a topic, event or person is reduced to its essential elements…who decides what is essential? History cannot be entrusted to a single writer, a single viewpoint. Such a history is at best incomplete, at worst, incredibly manipulative. We have taught generations as a whole to be disinterested, in its ‘richness’ and value. We have as a society, devalued history and, in so doing, left it at the margins so that we might go about our lives giving history and its impacts on our present lives, little to no consideration.

The past is passed, no sense in worrying over it. Anyway, we are each captains of our own fate, or so we are taught, our lives are ours to make of them what ever we want. History then is truly of no value to us. We have cast off the shackles of our past and do what we would please…only none of us truly do this. History clings to us whether we acknowledge its hold or not. It is sometimes said that those who refuse to examine the past are doomed to repeat it. And, why is this? Because the past shapes who we are and what we do. In not examining it, we choose to remain ignorant of what is at work within us. That is ignorance, not some inherent wisdom or freedom of choice. Ignorance is not bliss…it is only ignorance and choosing to remain ignorant leaves one mired in the past, a past that many would prefer that we stay ‘stuck’ in. Questions invite, for some, unwanted changes, changes that might call into question that which they have long considered as givens, foundational even to the way they have lived their lives. To question that is to question all that one has done and when what one has done has come at great cost to others. it lays bare the wrongs they have done.

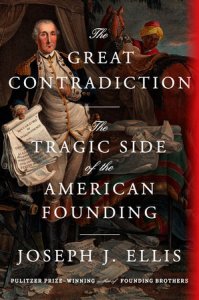

Joseph J. Ellis is an American historian whose work focuses on the lives and times of the Founding Fathers of the United States. His book American Sphinx: The Character of Thomas Jefferson won a National Book Award in 1997[1] and Founding Brothers: The Revolutionary Generation won the 2001 Pulitzer Prize for History. He was a professor of early American history at Yale and, as a historian, is widely respected by his peers. He examines his chosen topics thoroughly, even ruthlessly. It is not a historians job to dress up or excuse the behaviors of their actors and heroes. A historian must also protect himself from the danger of what Ellis calls ‘presentism’, that simple, and easy to fall into trap of when assessing the acts of those in a bygone era that we do so with the full knowledge that we possess today, and was unavailable to them then. There is a lot of that being done today. A person’s actions must be understood within the context of their time, not ours. An honest history does not seek to ‘whitewash’ its players, not hide what we today see clearly as their errors and warts. What is obvious today, was not then.. We cannot judge them by today’s standards, but we should and must assess them. A good historian presents them as full human beings, with their strengths and weaknesses, because they are simple humans like us. A mythologized history teaches people that we are less than those ‘great men’, that we are small, and have no effective agency in our world. That is a falsehood, and a manipulation, intended by the speaker, to disempower the listen, smooth away any obstacles to the speaker that a listener might otherwise present.

The world, many of those in positions of power will insist, is as it is and must be. But claiming such is a political act, not one of a historian or an impartial observer. All people possess agency and thus the ability to effect their world in some way. A historian neither denies nor excuses an actors weakness, their goal being understanding and to communicate that understanding to the rest of us. Theirs is not a plot to determine or undermine our history, it is to humanize it, to set it within context and to do so in a way ‘true’ to its own time, supported by the evidence, not the speculations and biases of a modern day observer. Ultimately the historian’s purpose is to provide the understanding of these events so that we might act rightly and effectively, free of the myths, biases, prejudices and flat out ignorant ideas we might have that keep us trapped in the mess the founders of this nation, collectively, left us with.

Ellis’ most recent book is a short one and he wastes no pages in his examination of what he sees as the central problem that has plagued us from the beginning, a problem which still splits and tears at us today, in a way as potentially disastrous as our Civil War. Ignorance and unexamined bias, fuels the hate that perpetuates it. At is center is the contradiction at our nation’s core. Ellis describes The Cause, the idea around which the American colonists rallied to throw off the rule of a distant king and tyrant. It was a war waged for individual freedom. Colonists of the time characterized their relationship with the king as parallel to that of master over slave, and roundly rejected it. Jefferson, in the Declaration of Independence, claimed that all people were created equal, that we all have certain inalienable rights, among them life, liberty and the pursuit of happiness. Ellis looks into the debates that occurred here on these questions and the agreements that were reached in order to present a united front to the king and Britain.

Slave holding was common throughout the colonies leading up to the Revolution. In the South they had built their economies on slave labor and argued strenuously, vociferously, that it should and must continue, or the south would end. In the north, at the time of the war, they were ‘weaning’ themselves off slavery, a condition that never reached the levels of the South. Virginia supported the ending of the importation of slaves…mostly because they were ‘producing’ more slaves than they could use and they were becoming its biggest ‘export’, selling them to owners in other states. The union of North and South was threatened by this question and so efforts were made to ignore it for various reasons, to allow its continuation, to set it aside until some future date, once independence was won and our fledgling government had a chance to solidify and provide security. Virginia, the most populous and politically potent state, included such statesmen as Jefferson, Washington, Madison and Monroe.

Adamant on the question of independence, they were also slave owners caught on the slippery moral slope, publicly, when pressed, into arguing against slavery, although working steadily to keep the slavery question from derailing their desire to create a ‘nation’. Privately, accustomed to the privileges afforded to them by slavery, they had grown dependent upon it and were confounded about how to do away with it. They all eventually failed. The South ‘won’ and slavery became institutionalized over the next 80 years! As Ellis points out while they were probably correct in that if they attempted to ban slavery from the outset a unified front against the king, would have failed, but by failing to act effectively on the slavery question, by failing to include Blacks, and Native Americans, in their definition of a man deserving of inalienable rights, they solidified slavery’s position in the American South, further underscoring the fact that most colonists, largely little educated, South and North, were prejudiced, believing blacks and native peoples inferior. For decades to follow the idea of emancipation ever being instituted, was rejected. Few whites could even consider the idea of living in mixed communities and the idea of miscegenation and mixed marriage, the ‘mongrelization’ of the white race, was considered repugnant, while at the same time such ‘unions’ happened regularly, with mixed race children the result, children, whom because of this ‘fact’ were themselves denied rights and enslaved. They could not, and would not imagine a country in which both lived free…and for many this meant the continuation of slavery indefinitely.

Ellis lays this out concisely in 195 pages. Read it. Think on it and pass this book around. There is so much here we must if this nation is to continue. We continue to bang up against this conflict as it is ‘built’ into our country. It’s continuation can only result in the expulsion, to where, or the annihilation of millions of non-white Americans. It offers no legitimate or effective compromise. If we cannot learn this through an honest and open examination of ours and the histories of other peoples and times, this country is doomed. This same unexamined, ugly, underbelly that has shaped this country from the beginning, is still at work today. It continues to lead us to ever more violence. By our collective refusal to expose and discuss it, it dooms us, both individually and nationally, to a fatal mediocrity, violence, unhappiness and unfulfilled lives. It is the ugliness many try to mask, that others today feel free to loose on the world around them.

The predominant issue in Ellis’ book is slavery and our inability to address its continuing impact on American society and politics. He writes of another national ‘sin’ and that is that of our policy of the removal of native peoples, read extermination, read genocide. George Washington, secretary of War, Knox, and then secretary of State, Jefferson, worked early on to address this, trying to establish a respectful relationship with the many tribes east of the Mississippi, treating them as sovereign nations, in a coordinated strategy, making treaties and concluding land sales under the control of the fledgling nation’s federal government, specifically, to be negotiated through the executive office of the president under the advisement and with the approval of the US Senate. Leaving this in the hands of the individual states, as it was initially under the Articles of Confederation, was leading to endless chaos and violence.

Some in government argued for a demographic strategy, a more ‘passive’ take over of tribal lands, but that would have the same effect the eviction/removal of all natives in lands east of the Mississippi. Washington, Knox and Jefferson soon realized that the quickly growing white population would continue spilling over into native territories. The US government was powerless to stop them. The demographic strategy was by default in play. Much violence ensued. The racist views of white interlopers, speculators and settlers gave them all of the permission they needed. The natives were an undeserving impediment to white progress and occupation. The overwhelming majority of the the new white Americans, saw themselves Virginians, or citizens of their state. There was no ‘nation’ to which they felt any allegiance. They had just thrown off a king and would not be tethered to another distant government that claimed power. No! Fuck that!.

They felt no particular affinity for a theoretical nation and so simply did what they pleased, continuing in an accelerating rate to occupy and steal native lands. Like blacks at the time, white europeans considered natives to be inferior, the defensive actions of the native people were considered gross acts of violence without any justification and they were in turn, treated with even greater violence. Natives were neither directly recognized nor protected under the Articles of Confederation, which granted individual states the right to deal with matters occurring within their own poorly defined and self-described boundaries. The later Constitution did little but offer them vague mention. Both of these populations were denied full personhood. While in both cases there were those who abhorred these practices, the Jeffersonian ideals and promises, defined in the Declaration of Independence, where denied to them. While not covered in this slim book, each such new group that came to this country, who varied from their white, protestant, English predecessors, were treated in a similar way. Catholics, Jews, Irish, eastern Europeans, Italians, Chinese, Muslims, the many Asian people to follow later, teh south Americans who came, all were treated poorly, rejected and denied, the promise of the Statue of Liberty often little more than a sick joke, something to help the white ‘us’ feel good about ourselves…the intensity of the rejection, the bias and violence each group of people collectively suffered, increased with the degree of difference perceived. Brought or allowed here initially for economic reasons, for their cheap and disposable labor, each group faced an up hill battle for protections and the recognition of basic rights. Today, even those previously allowed in have been made subject to deportation and the simple and humane defense of them, has been criminalized. In fact today, you must not only look like the white, christian, us, you must act and speak like us. Any less than this and the absolutely intolerant hammer of ‘Homeland Security’ will crush you. Read people!!!

The ugliness, the racism, the bigotry that has colored this country from its inception, has been given not just permission today, but is actively supported by the current misadministration, through its attacks on education, social welfare programs, science and expertise, women’s health and the very existence in this country of anyone but white, christian males, all stemming from this same rot that has existed in the ‘heart’ of America from its beginning. And all of this is being used by a relative handful of abusive billionaires to take whatever they want. In the book, “The Art of War”, its Chinese author, Sun Tzu, states that “the enemy of my enemy is my friend”. By that he says that one should pit one’s enemies against each other so that both are diminished while the ‘leader’s’ people and powers suffer nothing. When one’s goal is power, all other things, and people, may be sacrificed. The American people, in all of our forms, are expendable when such people are in command. In our case, our collective biases, habits, and prejudices, uninformed as we are, are used against us. By our silence, by our complicity, these same things threaten to reduce us as well. We are each reduced to tools of no value once our usefulness is exhausted. When power and control are the goal, all become expendable. No one has security in such a world. Such a world is ugly and joyless. Residents live in fear. The only goal becomes survival. And that is noi life at all.

Some of the related books I’ve read in the last year and a half:

Indigenous Continent: The Epic Contest for North America, Pekka Hämäläinen

The Burning: The Tulsa Race Massacre of 1921, Tim Madigan

Careless People: A Cautionary Tale of Power, Greed and Lost Idealism, Sarah Wynn-Williams

Crisis Averted: The Hidden Science of Fighting Outbreaks, Caitlin Rivers

A Fever in the Heartland: The Ku Klux Klan’s Plot to Take Over America and the Woman Who Stopped Them, Timothy Egan

Feeding Ghosts, Tessa Hulls

How to Be Animal: A New History of What it Means to Be Human, Melanie Challenger

Into the Wild, Jon Krakauer

*James, Percival Everett

*The Jungle, Upton Sinclair

Killers of the Flower Moon, David Grann

The Lost Trees of Willow Avenue: A Story of Climate and Hope on One American Street, Mike Tidwell

Northern Paiutes of the Malheur: High Desert Reckoning in Oregon Country, David H. Wilson

Origin Story: The Trials of Charles Darwin, Howard Markel

The Rediscovery of America: Native Peoples and the Unmaking of U.S. History, Ned Blackhawk

Shadows on the Koyukuk: An Alaskan Native’s Life Along the River, Sidney Huntington with James Rearden

Shopping for Porcupine: A Life in Arctic Alaska, Seth Kantner

Ten Arguments for Deleting Your Social Media Accounts Right Now, Jaron Lanier

Where Land and Water Meet: A Western Landscape Transformed, Nancy Langston

Why Fish Don’t Exist: A Story of Loss, Love, and the Hidden Order of Life, Lulu Miller

Everything is Tuberculosis, John Green

Treaty Words: For as Long as the Rivers Flow, Aimee Craft

The Comfort Crisis: Embrace Discomfort to Reclaim Your Wild, Happy, Healthy Self, Michael Easter

Beyond the 100th Meridian: John Wesley Powell and the Second Opening of the West, Wallace Stegner

The Wide, Wide Sea: Imperial Ambition, First Contact and the Fateful Final Voyage of Captain James Cook, Hampton Sides

The War on Gaza, Joe Sacco

Ultra-Processed People: The Science Behind Food That Isn’t Food, Chris Van Tulleken

Paying the Land, Joe Sacco

All or Nothing: How Trump Recaptured America, Michael Wolff

Peak Human : What We Can Learn from the Rise and Fall of Golden Ages, Johan Norberg

The Once and Future Riot, Joe Sacco.

Nobody’s Girl: A Memoir of Fighting Abuse and Survival, Virginia Roberts Giuffre

Nature’s Ghost: The World we Lost and how to Bring it Back, Sophie Yeo

18 Tiny Deaths: The Untold Story of Frances Glessner Lee and the Invention of Modern Forensics, Bruce Goldfarb

The Great Contradiction: The Tragic Side of the American Founding, Joseph J. Ellis

Brave New World, Aldous Huxley