Every gardener is a weeder. Gardens are created landscapes, often expressions of the individual gardener or, lacking of intent and design sense, those of a chosen designer. We live in our landscapes as active, responsible, creators, participants and stewards. Gardeners are trying to create a particular look or to grow particular plants native to their area, or with ornamental value or food plants to feed themselves and their families. Some of us are simply pursuing what we understand to be a healthy relationship with one’s place, to undo the damage and allow a new healthy and vital landscape to grow. These are landscapes of our choice. Our intention and control results in various volunteers and weeds finding their own place and so follows the need for weeding.

We watch carefully, monitor the impacts of our work, attempt to understand what result is moving us closer to our goal and which might be indicators of further loss. Landscapes and gardens are incredibly complex systems and anyone who claims to have all of the answers is fooling himself and you. Our landscapes are broken, by us and our predecessors. The Pandora’s Box of weeds and disruption was burst open long ago. The only way ahead is to find a new path. Weeds are here filling the niches we have collectively made and maintain for them. The more one is surrounded by aggressive, well adapted weeds, the more time we must spend controlling them. While this can be significant, gardeners mostly take the work in stride, a necessity to reach our goal, a goal which may be the simple act itself, of working in concert with our place…open to its teachings. Gardening, is a way of life, a smaller scale version of farming and the management of large ‘natural areas’ with their attendant commitment, rhythms and demands.

Non-gardeners however, view the entire process as a chore. They lack the relationship, a gardener has with the green and growing world. Weeding, for the gardener, can be a meditative experience, a time away from the demands of the rest of their lives, those things they have little control over. There is purpose, value and meaning in what they are doing. The non-gardener tends to see it more as just another demand on their time. One they want to minimize. To do this they are far more likely to neglect the ‘work’, hire a service and utilize herbicides (not to say that ‘gardeners’ don’t ever use herbicides.)

- A closer view of the packed Kochia seedlings. Obviously the vast majority of these can’t reach full size. This represents a hugely expansion of the source, which we have pulled and hoed, several thousand. The increased weed pressure represented by this patch could be overwhelming for us next year after the mature tops, with their seed burden, blow through the neighborhood.

- This is immediately south of our garage and driveway. I cut everything to the top of this waste pile/berm. The developers do nothing to limit their growth other than a later season mowing for fire reduction. The drought this spring has reduced the bulk of the weed growth this year.

- Common Mullein, Verbascum thapsus. The thick stems of the inflorescences contain enough moisture and nutrients to ripen the seed when cut down after pollination. Mullein doesn’t require supplemental water here. It has no problem spreading and outcompeting many natives on arid sites. Friends groups have targeted these for pulls in protected natural areas.

- Last spring, the bare soil in the distance is where the blanket of Kochia is growing this spring. I’ve cut down a 20′ perimeter around the two most exposed sides of our property which was dominated by Flixweed, Hare Barley and Cheatgrass. This year, unsurprisingly, Kochis is a dominant ‘player’.

- Taken about a month earlier in the spring.The light gray-green of Kochia is forming a solid carpet where last year, nothing grew. Growing this densely not all of them can reach full mature size, an individual capable of growing over 6′ tall.but

We live in a new development… an unfinished one of 40 acres, in which probably 24 acres haven’t been prepped with the necessary grading, street construction and installation of utilities, sitting vacant and weedy, areas which support many thousands of weeds and millions of seeds, constantly reinfecting our own yards and gardens. The project has been ‘paused’ until economic conditions are more supportive. The developer, the owner of the weedy property, doesn’t see the care of this land as a priority. They don’t see it as a problem at all. It is, according to them, our problem and is easily correctable through the magic of chemistry and the regular use of herbicide. They have no understanding of the complexities of a landscape and no interest in learning.

I was a bit surprised to see a ‘worker bee’, hired by the developer, and out in the circle, a central roundabout of about 2 acres, spading out Mullein, Verbascum thapsus (This was a Wednesday morning, he came back briefly on Friday and on Saturday firing up s string trimmer to cut everything else down over the following couple of days). The Mullein is an aggressive spreading Eurasian weed that grows as a biennial. The first year it forms a low felty rosette of a foot or more in diameter, while the following year at least one flowering spike, shooting up from 3’ to 7’. A single plant can produce as many as 180,000 seeds. This is the way of annuals and biennials. Their survival is dependent upon the production of mass quantities of seed. It invades both disturbed sites like the undeveloped property here, made landscapes, as well as intact native plant communities. There were only a handful of these last year, probably over a few 100 this spring. The developer had made a failed attempt to establish Red Fescue in the ‘circle’ here last year, simply broadcasting seed without doing any weed control or prep before hand. This was followed up by insufficient irrigation over the spring establishment period.

I was a bit surprised to see a ‘worker bee’, hired by the developer, and out in the circle, a central roundabout of about 2 acres, spading out Mullein, Verbascum thapsus (This was a Wednesday morning, he came back briefly on Friday and on Saturday firing up s string trimmer to cut everything else down over the following couple of days). The Mullein is an aggressive spreading Eurasian weed that grows as a biennial. The first year it forms a low felty rosette of a foot or more in diameter, while the following year at least one flowering spike, shooting up from 3’ to 7’. A single plant can produce as many as 180,000 seeds. This is the way of annuals and biennials. Their survival is dependent upon the production of mass quantities of seed. It invades both disturbed sites like the undeveloped property here, made landscapes, as well as intact native plant communities. There were only a handful of these last year, probably over a few 100 this spring. The developer had made a failed attempt to establish Red Fescue in the ‘circle’ here last year, simply broadcasting seed without doing any weed control or prep before hand. This was followed up by insufficient irrigation over the spring establishment period.

As usual they were unreceptive to my suggestions. The resultant spotty Fescue plants are far from adequate as competition for the dominant weeds. (Incidentally, these were cut low themselves by the string trimmer this spring, further stressing them and compromising their ability to compete with weeds especially given our very dry conditions. They receive no supplementary irrigation.)

So far, little effort has been made to control/eliminate any of the other weeds, particularly the invasive Cheatgrass and Hare Barley. The seed of these latter grasses blow or are easily carried by animals, and ourselves, into our surrounding landscapes and the rock filled swales where they germinate readily. Ours is a windy site, frequently with gusts in the 15-30 mph range. The circle produces many 100s of thousands of these weed seeds, the surrounding property, far more. Those weeds greatly increase the ‘weed pressure’ on our yards and the resultant work we must do to keep our yards weed free. Those seeds that don’t germinate the following season add to the ‘seed bank’, lying dormant until conditions are more supportive of germination. Many species have seed that can lie dormant for years many of which are perennials and depend on their dormancy, assuring that seed remains viable, and available, for years when conditions are more supportive of their success….Annuals are more dependent upon their annual renewal, their production of seed while perennials, although slower to respond and dominate a persist.

Every region will have its own particular array of weed species, however, many are shared across the country. The latter is often the case because our pattern of development and maintenance practices are largely shared. We tend to ‘apply’ the same landscape formula with little regard, but for the most persistent and resistant site conditions. Whether from desire or marketing efforts our choices follow narrow patterns the differences largely determined by those climatic factors such as temperature, humidity and length of growing season which are unchangeable, although our tendency is to deny these native ‘realities’. Our landscapes from place to place tend to repeat forming a character that defies regional differences. New local development in Redmond then tends to resemble those of California if financial resources are similar…and the weeds which plague them are much the same. It is in the broad and dominant surrounding landscape, awaiting urbanization, which although ‘disturbed’, often almost totally, due to agriculture and other uses, but not supported the necessary supplemental irrigation, on which the weeds can vary significantly. Remove the magic of water from the typical ‘urban’ type landscape here and it won’t take long for even those commonly shared residential weeds to yield and those plants most adapted to our particular ‘steppe’ conditions, upon finding opportunity, move in. The weeds which invade these vacated and disturbed, neglected landscapes, have ‘travelled’ here from native homelands with similar conditions, in our case from the Steppe regions with similar continental conditions.

- Bur Buttercup one of our newer threats.

- Tumble Mustard. Very common on disturbed dry sites here. These break off in Fall scattering their seeds as they ‘tumble’.

- Another weedy mustard this one not so common yet, but if left uncontrolled?

- Flixweed. Another mustard this one often germinates forming a solid cover in places here across the neglected pasture land and easily germinates and grows on owners property.

- Malva neglecta, Common Mallow. Related to Hollyhock and Hibiscus, this perennial can form dense mats, quickly sending down taproots that are impossible to pull by hand.

- Easy to pull at a young stage, but fence lines and path edges can be thickly infested. This is the classic ‘Tumbleweed’ raised to almost iconic status by TV westerns and movies, even though it has no place here as an invader from the Russian steppe. https://oregonflora.org/taxa/index.php?taxon=8107

These include several species of weedy mustards here which can dominate. including Tumble Mustard, Sisymbrium altissimum Flixweed, Descurainia sophia and Purple Mustard, Chorispora tenella. Four species of Knapweed, Centaurea spp., while currently infrequent or absent on this property, are in the ‘wings’, two finding space in Dry Canyon Park; Tumbleweed, Salsola , is so common across the arid west that many have come to see it as an iconic plant of the West, even though it travelled here from the Russian Steppe as did the aforementioned Knapweeds and Cheatgrass; several Nightshades, Solanum spp.; at least two Pigweeds, Amaranthus; Lambsquarters, Chenipodium album; Scotch Thistle, Onopordum acanthium; and Kochia, Bassia scoparia, another one of those ‘tumbleweeds’ from the Steppe, single plants of which can produce thousands of seed. There are other nastier weeds like Puncture Vine in the adjacent neighborhood, which will find its way here given the lack of a weed management program here…and Puncture Vine, Tribulius terrestris, painfully does exactly what its name suggests, fully capable of flattening bicycle tires, penetrating vehicle tires to be carried off site where the barbed seed capsules break open infecting new sites.

Annuals are especially adapted to movement and early invasion given their high seed production and germination rates. Their annual life cycle and our continual disturbance of our occupied landscapes, assures that the particular weed mix is highly variable and open to new ‘players’ as they arrive traveling down available corridors, roads and railways, trails and rivers, facilitating the movement of seed, often with our assistance, intentional or not through both our own movements and those of the goods and services upon which we have come to depend.

Bur Buttercup, Ranunculus testiculatus, is a relatively new, rapidly spreading, weed in this region and is very successful on compacted soil such as those places people repeatedly walk, on and adjacent to trails, both recognized and ‘desire’ (I just saw 1000s of these on top of Bend’s Pilot Butte, where people walk around randomly, obliterating what native vegetation remains.) The little burs, visible above, contain multiple seeds and stick to clothing, fabric, fur and other surfaces aiding their transport and spread.

Bromus tectorum, Cheatgrass. This is the incredibly aggressively spreading grass from the Russian steppe, that out competes so many natives for water in the arid intermountain west. An early season grower it also serves to fuel more common fires and is in fact aided in its dominance by frequent fire. This produces viable seed by the very early summer so must be controlled early.

Hare Barley, another weedy, long awned, weedy grass, which grows early and thickly, outcompeting natives. When mown late, after seeding, as it was last year it seed is blown far and wide.

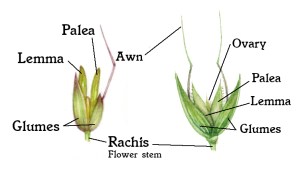

The ‘wispy’ inflorescences are the compound flower heads of Cheatgrass will turn red as the seeds soon ripen. Grass flowers differ from what most people expect in a flower as they have no petals, replacing them with the rather plain structures of lemmas, glumes and palea. But these are the centers of reproduction from which their wind borne pollen is released and where the seed producing ovaries are located. The narrow needle like awns, firmly attached to the seeds, are what catch in our socks and in the ears and paws of our dogs which can lead to infections and vet bills.

Grass flowers form in characteristic structures such as spikes and panicles, ‘branched’ and unbranched.

Pictured to the side is a planted ornamental grass taken over entirely by Cheatgrass in one of our yards. It is difficult to pull any weed out of the crown of an established plant.

Non-gardeners tend not to recognize weed problems until well after they have exploded across the landscape. A plant, here and there, for them, is not significant. Waiting, however, allows a species to not only secure ‘access’ to a site, but allows it to become firmly established with a significant local reproducing population and the capacity to spread and persist, adding ‘invisibly’ to the ‘bank’ of seed in the soil itself and in the case of perennials, building up root systems from which new plants, clones of the parent, will continuously arise, and, depending on the species, from which may persist even after herbicide applications, especially when poorly timed or otherwise misapplied. A single plant, especially, those like many annuals and biennials, which spread predominantly by seed, which they produce in high volume, can be enough to begin a successful invasion. Regular monitoring and timely action are then necessary as long as the threat is ‘nearby’ and under conditions such as ours which are common today, this will be a given for the foreseeable future. The single Scotch Thistle plant in the circle was a case in point. (I recently found another ‘patch’ of this on the property immediately south of our development, different owner, currently being grazed, but in the planning process to be developed as more residential property. I suspect controlling these may be of no concern for those now committed owners, much as are our own.) If left alone, a single plant can produce between 10 and 40 thousand seeds, the ‘problem’ increasing exponentially. These can quickly grow into pokey, impenetrable masses of Thistle rising overhead. This species is coarser and whiter, ‘fuzzier’, than any of our other local thistle species, including those several weedy species and our one native.

Scotch Thistle. There was none of this last year. This plant is in the ‘circle’. A biennial they stretch over 10′ tall and form impenetrable, prickly, barriers, even to cattle. Some range lands in Crook County have been overwhelmed by this weed.

Any weed, especially annuals and biennials which reproduce entirely by seed are very likely to seed into, or very near, the crown of desirable plants making their extraction difficult to impossible. This is especially true for grasses like Cheatgrass.Any herbicide that would ‘control’ the weedy grass will have an effect on the desired one, a common situation in landscapes today even when homeowners/gardeners are relatively consistent in their weeding and care. Weed seed tends to be ‘caught’ in established plants where they can grow and establish for some time before ever being noticed, from which they are difficult to extract and/or control. Prevention is always the best strategy, but that requires knowledge, an active monitoring program, minimizing seed sources and timely action.

Any weed, especially annuals and biennials which reproduce entirely by seed are very likely to seed into, or very near, the crown of desirable plants making their extraction difficult to impossible. This is especially true for grasses like Cheatgrass.Any herbicide that would ‘control’ the weedy grass will have an effect on the desired one, a common situation in landscapes today even when homeowners/gardeners are relatively consistent in their weeding and care. Weed seed tends to be ‘caught’ in established plants where they can grow and establish for some time before ever being noticed, from which they are difficult to extract and/or control. Prevention is always the best strategy, but that requires knowledge, an active monitoring program, minimizing seed sources and timely action.

Herbicides, while theoretically effective, have limitations and can result in much unintended damage. They are sold as labor savings technology, as ‘silver bullets’, but their ‘costs’ are widely ignored by society. Their use becomes habitual and to be effective, people often plant singularly, their plants widely spaced with room to effectively target the unwanted weeds while avoiding damage to their desired landscape plants. Such spacing is unnatural and works against the establishment of healthy plant communities, while preserving bare ground which is susceptible to weed invasion, which demands continuous weed control efforts. Regular herbicide spraying then both allows the owner to achieve their weed free goal, while assuring that their efforts never end or even diminish. It is an incomplete and flawed strategy when pursued without a broader and more sustainable approach. Regular herbicide use is a strategy that assures that balance, health, homeostasis in the landscape, are never attained. It works for and against us. It is then a coping mechanism which assures that the agro-chem industry remains highly profitable. Such a strategy is akin to a medical strategy that holds as its goal an absence of disease rather than a state of health. It in fact, dismisses health and homeostasis as desirable and attainable. It accepts a world of broken plant communities while rejecting the very idea of pursuing health. It accepts the idea that disease and infection are a given and easily manageable via chemistry. Health and the billions of years of life which brought it about and continue to support it, is ignored. Along with this chemical approach, complexity and diversity are rejected. The reality of disturbed, unhealthy landscapes, is today a given, and management via chemistry remains the preferred strategy despite its negative contributions to the problem. The disruptions caused by the very chemistries we use to limit the ‘spread of infection’, of weeds, leads to more and is acceptable as its use adds to economic growth. Health, in an undisturbed landscape, with properly functioning relationships, adds little directly to an economy. Its ‘gifts’ were ‘free’…at least until we so compromised the natural systems and cycles which have supported it all along, that they require ever more intervention/slash opportunities for economic growth. Health is thus sacrificed for the abstraction of economic growth. The economy grows as health declines….

As long as seed invasion is uncontrolled our landscapes will be highly compromised ’battlefields’. The crowns of such plants like this one above , will likely necessitate its removal and replacement. Some go as far as to suggest managing their landscapes as chemically treated dead zones, choosing no plants at all over the tedium of selective weed control. While that reduces seed production it leaves it prime territory for invasion. ‘Nature abhors a vacuum’, is a saying of import. And of course such dead zones offer nothing to support/attract birds and wildlife. They do nothing to promote the health of surrounding landscapes other than through the absence of a weed source, at least until the owner gives up on his chemical path.

A healthy plant community can suffer disruption and recover over time. These can be even quite large as evidenced by cases of massive landslides and volcanic eruptions…however, when local plant communities have been sufficiently disrupted and support exotic, aggressive weeds, the process is forced out of its path. The introduction of new species can disrupt these communities especially when they occur too frequently with many of the relationships upset at the same time. Under those cases homeostasis may require many more generations over which additional disruptions are not imposed. With health comes a resilience, an ability to recover from disturbance/infection, whether at an organismic and community scale, but even then a healthy state can tolerate only so much disturbance over a given period. Too many challenges, too great a stress, will upend even a healthy system. Health depends on on these relationships. Change too many elements at once and the whole is threatened. Exotic plants can fill some of the beneficial roles as long as relationships are respected and the new plants mimic their native cousins and wildlife both recognize and can utilize them.

Weeds are a product of our modern society. In a very real sense they did not exist before us, before we began ‘disrupting’ their communities and moving them around. Plant communities lived in homeostasis, dynamic balance. Changes to their populations were incremental proceeding largely at the pace of evolution. At such a pace change was gradual and communities were able to adjust. We have served as an accelerant and as a randomizing force, continuously changing the composition of communities at a rate far beyond which communities can adapt. Because we have done this very often, with very little consideration for the health of the communities themselves, our impact has been one that breaks existing relationships without much thought given to the health of the whole.

Weeds are plants dislodged from their former relationships. Those which can tolerate this state of change and adapt to the pattern of development we tend to impose as we move from place to place, succeed. We call them weeds. Those that fail this ‘test’ are forgotten. Occasionally we purposefully or accidentally move a plant to a region to which it is ideally suited and these plants invade even undisturbed sites aggressively. We call these invasive. As humans, and social beings, we follow particular patterns of ‘development’ as we move around. We tend to create and maintain these. We thus give preference, unintentionally to particular plants, We become a kind of chaotic selective force in the evolution of plants and their communities. We ‘shape’ them, upending the relationships which our local natives depend upon. Those individuals best suited dominate while those less so, die out or reduce in proportion. It becomes a numbers game after introduction, the most aggressive, the best adapted, selected, those less so, being outcompeted at a rate which greatly outpaces our own, as they follow their annual reproductive cycle. Plants respond to the conditions around them. We, especially when we dismiss them, tend not to consider our own involvement, our practices. When we change our practice, we change the selective forces and with them the balance of the community. Plants, and their communities, are thus more elastic and responsive than we are.

Natives live in their long held relationships. Abruptly changed, often destroyed, natives while well adapted to climate haven’t had the long associations with humans, our patterns and the rapidity of change we impose on our landscapes. The weeds which have followed in our wake of movement and change are a better ‘fit’ and the thousands of species that follow with us, especially with agriculture and trade, eventually succeed when their particular strengths are matched with the conditions of the region they find themselves in. Of course those poorly adapted continue to follow along in the wake of our disturbance waiting for their own opportunity. Successful weeds then pose a companion ecological crisis, natives already suffering the assault of directed disturbance, are then challenged by aggressive and adapted invaders. In such a weakened state, natives lose what ‘advantage’s evolution may have endowed them with. These new interloper weeds pose a serious threat to the compromised native community, outcompeting them, crowding them out and depriving them of limited water and nutrients…Shock and awe, the assault is often overwhelming, when the native landscape faces the, typical urban and agricultural development. All of this occurs largely beyond our awareness, given our own lack of relationship with our landscape, our own peripatetic habits and our demand for goods and services originating from far away; our use of the land; and our collective attitude toward the living world…how we either value it or discount it. All of the organisms a landscape contains, the plants, the birds, fish and wildlife, the insects native here, even the fungi and bacteria, depend on and play roles in its healthy continuation. All of life lives in relationship while we, with our power and consumptive appetites have stepped outside of its cycles and obligations. Weeds, functionally removed and transformed as they are, add to the disturbance of the landscape out of sync.

Uncontrolled weed spread is not part of the natural healing process. Rather it is a part of the continuing and worsening spread of infection, at least until we recognize our own roles and change our behavior. We have necessary and largely ignored roles here. We could choose to both develop and maintain the landscapes here more sensitively with an eye on their overall health recognize our responsibilities to it, or continue to ignore and discount them.

Far too often property owners and mangers fail to recognize the value and biological complexity of their property. Caring for it is viewed as an unnecessary cost. This is the case with our project’s developers. They have no management plan nor do they recognize the need for one and act as responsible stewards. The built landscapes as they are, are what some of us call whatever was on the truck landscapes, plants chosen from a very limited palette and planted with little thought to either their relationships or an aesthetic. Drip irrigation systems are installed and the resultant landscapes are said to be xeric. Plants with differing water preferences are planted together and watered to keep the least drought tolerant of them growing vigorously, overall generally over watering the majority.The idea of and practice of stewardship are no where on their radar. Plants, in general, are dismissed as simple, their differences of little consequence. Plug and play. A transitional landscape which could fill the endless open niches of broken and devastated landscapes, isn’t considered worth the expense or effort. Weeds are simply left on their own placing a continuously increasing burden on those in the area who are working responsibly. It’s another case in which one’s freedom to do nothing, even when it places a sizable burden and costs on those who act more responsibly, is recognized by wider society. Being a ‘bad’ plant citizen is acceptable. Once again the ‘right’ of those who refuse to recognize the health and rights of others, takes precedence. ‘You can’t tell me what to do!’ Herbicides are accepted as the preferred weed management tool, when they do anything. It is ‘easy’ for those who don’t want to be bothered. As long as this holds, the landscape ‘loses’.