Clarno Formation – 54 to 39 million years ago.

Getting back to Central Oregon, the Clarno Formation formed much of the region’s base rock, an accumulation of volcanic rock, their sediments and soils in layers to as much as 6,000’ thickness. 6,000’. The area was what geologist call an ‘extensional basin’, a broad low basin between the Blues and Wallowa Mountains and the accreting and volcanic landscape forming to its west.

As the Clarno was forming so was Siletzia off the coast of Oregon, Washington and British Columbia, building up relatively rapidly from intense and volcanic activity between 56-49 million years ago to the west. Siletzia was then accreted to the continent due to plate tectonics. In Oregon this terrane became the area we now recognize as our Coast Range and Willamette Valley.

This area looked far different before this period than at its end. It looked far different again, from when it attained its maximum elevation, to how it appears today. Trying to tack all of this is a bit like trying to follow a 3 ring circus…with many more rings, all proceeding at the same time, with generous overlaps. When looking at our landscape we are faced with the problem of the never ending processes of ‘addition’ and erosive ‘subtraction’. The ‘end’ of the period we define as the Clarno Formation is not one of some final result. The regions canyons, have today been deeply eroded, cut steep, with broken slopes, below the rim tops we see today. These were very different 39 Ma and they will look far more different in another million or ten million years from today, likely unrecognizable to us. Even if we were able to somehow survive until then to observe them, our ‘snapshot’ and pliable memory of them would have likely transformed over the many centuries. Erosion will have been at work over the intervening time together with those forces working to ‘build’ and ‘lift’, the working of plate tectonics locally continuing to drive the process as they continue in their slow motion crashing, transforming the surface from below.

During the Clarno those forces continued with, explosive eruptions, lava and pyroclastic flows, lahars that poured down from volcanoes of the Mutton Mountains in the formations northeast corner and Ochoco Mountains area, just west and south of the Blue Mountains, along with their mudstone, and conglomerates derived from the erosion of both accreted terranes and that of volcanically ‘built’ structures. And thus was ‘built’ the Clarno and the later John Day Formation. The three largest volcanic structures of the period in the Ochocos remain today as the Crooked River, Wildcat Mountain, and Tower Mountain Calderas. These volcanos have not been active for many millions of years. The center of volcanic activity in the region began to shift westerly during the Clarno with the tectonic changes accruing to the expanding continent’s edge developing into what would be the Cascade Volcanic Arc. The Ochoco Volcanic Area remained an active factor on through the development of the John Day Formation Period.

The short trail at the Hancock Station, of the John Day Fossil Beds National Monument, here showing the hardened mass of a Clarno Formation lahar.

The Clarno area formed as an extensional basin or series of basins, near sea level stretching west from the Blue Mountain, Ochoco Mountain area, with its accreted terranes, and the emerging, low West Cascades to its west. Early on the region had a warm, sub-tropical and wet climate. The earth’s climate was overall far warmer then, without polar ice caps and a different mix of gases in its atmosphere. It existed under what we would consider ‘greenhouse’ conditions. What was the Pacific Northwest was an aggregation of accreted terranes hugging the continent, which itself was nearly 800 miles east and slightly north of its local global position today. S

iletzia, as mentioned above, the western most, youngest terrane, was recently added. The stratigraphy, the layers in this region, are many and complex, in places exhibiting ‘folding’ that could have only occurred under immense pressures over geologically significant time periods. It has been extensively studied in road cuts, canyon walls and excavated trenches. The later John Day Formation overtopped much of this area adding to the thickness of its crust, infilling low places. Because of extensive erosion and canyon forming, much of the ‘younger’ rock, which was layered on top, has been transported away and deposited as sediment elsewhere. Volcanic activity gradually moved westerly as a result of plate movement, moving the subduction zone, that feeds the material for the volcanic activity, further west. This resulted in the activation of the Cascade Volcanic Arc which continues into the present.

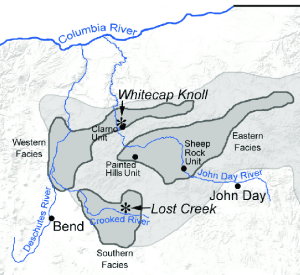

Map showing the distribution of the Clarno and John Day Formations in central and eastern Oregon, as well as the location of the three units of John Day Fossil Beds National Monument and other localities mentioned here. The Clarno Formation is represented by light shaded area, while the eastern, western, and southern facies of the John Day Formation are represented in darker shading. Map modified from Robinson et al. (1984) and Albright et al. (2008).

The map right shows the area of the Clarno Formation in light gray that built up over this period. Prineville lies within it, Redmond near its southeast most extent. The Clarno produced much of the base rock underlying the region south to the Smith Rock area and west to and across the present day Deschutes River, just to the north of present day Redmond. Bend lay south. The High Cascades would of course not form for many millions of years. The older West Cascades began forming while the Clarno was underway, reaching their highest elevation some 15 million years after the Clarno Formation was completed, so around 25 million years ago. The central Oregon region, with a much less mountainous barrier to its west, a far lower elevation, was under the more direct climatological influence of the Pacific during this period and was both wetter and warmer overall in general. Again, keep in mind that these ‘events’ occurred over millions of years and the transitions with them.

The region was not one day mild/tropical and the next arid/continental. The West Cascades formed and the Clarno region rose in elevation, erosion proceeded apace, more forceful as the elevation and grades increased. The darker gray areas show distinct facies, or rock types, with shared characteristics from different volcanic centers geologists have traced, attributed to the later, but related, John Day Formation. The volcanic vents in the area over this period were several, the volcanoes and cones, now mostly worn away in their entirety or buried in the accumulating ‘products’ of later John Day Formation events, all a part of the Ochoco Volcanic Complex. When we tell ‘stories’ of such events we have a tendency to frame them in more strict and definable limits so that we might better understand them. Open ended processes, that ebb and flow, transitioning over such long periods, beyond our experience, complicate this, while ‘encapsulating’ such events into manageable size, distorts their actual unfolding.

Formation of the West Cascades occurred between 54 and 24 million years ago and have long since eroded down to relative nubbins, the eroded sediments of their eastern flanks moved and spread eastward into the paleo-Deschutes River Basin helping raise what would become our local landscape. The volcanic activity and number of vents would be far greater in the younger High Cascades to follow. The Cascade Volcanic Arc maintains a position relative to the Cascadia Subduction Zone and ‘appears’ to be gradually moving east, but it is the continent that is moving west. This may seem contradictory at first. Apparent movement is dependent on perspective and who or what is moving relative to that ‘observed’. The faults and fissures below the Cascades are relatively fixed while the crust above slides westerly, taking us and everything else on the surface with it.

Crooked River Caldera formation (CRC)-

The Crooked River Caldera figures large in our local geology. It is dated to almost 30 mya. Originally a truly massive volcano complex of vents it abutted the Deschutes River Basin to its west, built up earlier as a part of the John Day Formation possibly as a product of the ‘Yellowstone Hotspot’. The ‘hotspot’ has remained stationary as the North American Plate continues moving westerly, giving the impression that the hotspot itself is moving east, but no. Calderas can occur when the magma chambers below a volcano empty creating an instability above leading to its collapse. The caldera is ‘framed’ by a series of fractures/faults which juxtaposed much older rock, from the Clarno Formation, with that of the later John Day Formation, creating a weak zone. The John Day Formation continued on millions of years after the collapse obscuring much of the caldera itself especially to the east.

The Crooked River Caldera figures large in our local geology. It is dated to almost 30 mya. Originally a truly massive volcano complex of vents it abutted the Deschutes River Basin to its west, built up earlier as a part of the John Day Formation possibly as a product of the ‘Yellowstone Hotspot’. The ‘hotspot’ has remained stationary as the North American Plate continues moving westerly, giving the impression that the hotspot itself is moving east, but no. Calderas can occur when the magma chambers below a volcano empty creating an instability above leading to its collapse. The caldera is ‘framed’ by a series of fractures/faults which juxtaposed much older rock, from the Clarno Formation, with that of the later John Day Formation, creating a weak zone. The John Day Formation continued on millions of years after the collapse obscuring much of the caldera itself especially to the east.

The roughly elliptical caldera, across which the Crooked River now cuts, is about 27 miles by 17 miles. It is thought to be the seventh largest caldera on earth and was the largest single volcano of its time within the current borders of Oregon. There are multiple rhyolitic ‘intrusions, vents, bordering the caldera associated with surrounding faults, many of which occurred after the caldera’s collapse. This area was volcanically active for many millions of years building up the ‘original’ volcano, prior to the collapse, as well as after it, which resulted in many of the prominent buttes in the area today. The resultant complex includes Smith Rock, Gray Butte, Haystack, Grizzly Mountain and Powell Buttes which are located near its NW most and western edge. While erosion wore away much of the remaining caldera ‘rim’, later flows, including those from Newberry, the broad low vent of Grass Butte near the Prineville Airport and others of the later Deschutes Formation, built up the lower ground to the Caldera’s west and south. Low areas between these flows filled over time with sediments from the nearby rhyolitic domes, such as the area of the present day farming community of Powell Butte. My brother, who did GIS for the Ochoco National Forest, worked with one of the geologists who first ‘described’ the CRC. These events effectively hid the caldera which was only ‘discovered’ in 2003.

When the volcano collapsed there were in addition to lavas, pyroclastic, flows, of superheated gases and mineral material which later cooled into volcanic tuff. These local tuffs were ejected at thousands of degrees from vents, such as those at Smith Rock forming the characteristic buff colored cliffs along with the darker basalt material which cooled into the accompanying ‘plugs’ exposed now by millions of years of weathering, erosion. Much of this tuff filled the caldera and spread eastward from present day Prineville.

It is likely that the Smith Rock ash flows spread out across the landscape westerly coalescing on the ground over what is now the Redmond area burying the landscape in several hundred feet of tuff. Keep in mind that this layer has been overlain by numerous later lava flows and sediments. Smith Rock itself has eroded considerably from its former maximum size exposing the tuff cliffs and basalt plug that remain.

Standing near the City of Redmond’s newly drilled well #9 today, where Antler crosses the Dry Canyon floor north of the Spud Bowl, likely places you some 125’ above the former canyon floor. The basalt rims on both sides above you were deposited as a part of the Deschutes Formation some 5+ million years ago, well before the Newberry flows which pushed the paleo-Deschutes into its course here, where it began cutting the canyon along what would have been the revised ‘fall’ line of the drainage basin.

The formation of Gray Butte, Juniper, Haystack, Powell Buttes and Grizzly Mountain, have older rock associated with the Clarno Formation at their base and were for many years a puzzle for geologists. Part of the ‘confusion’ over the origin of this areas was created by the Cyrus Springs Fault Zone that runs through the area and demarcates the edge of the caldera collapse, again, unknown until recently, tilting and ‘breaking’ the strata of their earlier formation. The reason for this fault was long inexplicable. These buttes are rhyolitic ‘domes’ and intrusions formed after the collapse and are aligned with the perimeter fracture zones, which conducted the flow of magma to the surface. These are believed to have arisen as single events of extruded, very viscous, lava which solidified before they could spread. All of this and later flows created a ‘muddled’ ‘picture of our local geology.

The John Day Formation –

30 to 18 million years ago, this formation developed covering much of the John Day River basin to just south of the Ochoco Mountains, into the upper Crooked River Basin, beneath layers of sediments, lava and pyroclastic tuffs. Much of it was layered on top of the rock of the earlier Clarno Formation. (It is difficult for me, non-geologist, to figure out where the Clarno ends and the John Day begins. These layers often alternated between volcanic and thick layers of eroded sediments, which eroded from far older accreted terranes, filling canyons and lower elevations, exposing more intact portions of these terranes which still contain intact fossils of ancient sea beds. The Periods overlap and as the map shows, they are often considered together.) Where elevation and vents permitted, later the Columbia River Basalts would over top both of these filling in the low spots, burying more northerly locations. It is difficult to imagine this area, with all of these overtopping layers, resting at or below sea level. Through these volcanic vents, the Ochoco Volcanic Complex built itself up contributing its own volcanic layers. The Crooked River volcano complex and its resultant Caldera occurred during the John Day Formation, which outlasted it, going on to obscure and bury much of the Caldera’s eastern and southern bordering edge. While there were various other vents in the complex, the most significant were three volcanoes, all of which eventually collapsed forming calderas, the Crooked River Caldera, the largest, within which Prineville is located today; the Wildcat Mountain Caldera, between Prineville and the Painted Hills; and the Tower Mountain Caldera, northeast of Sheep Mountain.

The Columbia River Basalt Group (CRBG)-

Originating in far eastern Washington and Oregon, these built up layer upon layer flowing along the Columbia River, eventually all of the way to the Pacific. Not how these spread across the area of Mt. Hood, which hadn’t formed at the time.

These were a complex that combined to form the largest such flows of ‘flood basalt’, in the PNW over topping the more ancient landscape. This event is the accumulative effect of more than 350 individual lava flows occurring between 16.7 Ma to 5.5 Ma (million years ago) of a volume totaling 41,800 cu. mi. of lava (that would fill a cube 35 miles square by 35 miles tall). It would cover an area 204 miles by 204 miles to a depth of 1 mile on average. This group of flows was comprised of eruptions originating from seven different centers of generally north-northwest-trending linear fissures, deep fractures, ranging from a couple to over a hundred miles in length each, similar to the fissures and eruption over the winter of 2023-’24 in Iceland, but on a far, far, grander scale. Most, 93%, of the flood basalt volume erupted in a time span of about 1.1 million years (around 16.7 to 15.6 Ma). These include those from what is sometimes called the Steens Mountain Basalts, the southeast most flows of the Group.

Why call these ‘flood basalts’? Lavas differ in temperature and chemical makeup which go to determining their viscosity, their ‘thickness’, the degree to which they ‘stick’ together. Lava and water are both liquids, but lava is far more viscous/thick, between 10,000 to 100,000 ‘thicker than water. As ‘liquid’ basalts these flow more slowly and with a greater depth across a surface than water. (For comparative purposes the rhyolitic magmas that formed the intrusions, domes and buttes around the CRC had a viscosity of between 1 and 100 million times that of water, which goes to explain their lack of spread and the verticality of the domes and buttes in the area.) Flood basalts do flow ‘downhill’, but its viscosity and the pressure driving them can cause them to flow above the surrounding terrain. As a liquid it conducts pressure, force, within itself, pushing itself as gravity draws it. A flow several feet thick will easily ‘push’ itself over objects in its path, to a point. Its later solidified surface won’t be flat and smooth like a lake, but will reflect in part the surface below over which it flowed The lava upstream, will tend to ‘push’ it up and over. Think of a river driven downstream over rocks and barriers, but slower, more massively.

Temperature is a big factor. Surfacing typically at between 1,470 to 2,190 °F, lava contains a lot of heat it must lose before it solidifies. This takes time, so the lava moves following the contours of the ground beneath it, cooling at both that interface and where it is exposed to air. Hot enough, with low viscosity it flows fluidly, more uniformly. As it cools and thickens the outer surface may begin to form an insulative ‘crust’ above, sometimes forming ‘tubes’, the liquid lava within then able to flow much further protected in a shell. Hot enough, with steep enough grades, flood basalts can then flow many miles depending on conditions, tens to a hundred or more feet thick if the ‘event’ is big enough without forming ‘tubes’.

The chemistry of the rock/lava effects their viscosity and the way that it can flow. Less viscous, lavas can flow more quickly, ‘thinly’ across the surface and potentially further while at the same time accumulating to great depths as it flows filling basins and canyons. Basalts containing more silica in their composition tend to be more viscous, thicker, less ‘liquid’, even at comparable temperatures, moving more slowly, more commonly forming ‘chunks’ that seem to float and tumble in the flow. Magma and lavas, names assigned to the same materials, magma its name before it emerges on the surface, after which it is called lava, with silica contents up to 70% making them far more viscous. These high silica lavas are termed ‘felsic’, and also contain more volatile gases which are lost much more slowly and tend to lead to more explosive eruptions. Flood basalts are lower in silica, generally in the low 50% range and only slightly higher, contain less volatile gas and aren’t so prone to explosiveness. Most of the earth’s crust, its rock, is composed predominantly of silica, 59%, with varying amounts of other minerals.

McDermitt caldera, straddling the Oregon-Nevada border, was formed near the beginning of this period. McDermitt is the western most defined caldera, agreed to be a part of the long string of others stretching across Idaho to present day Yellowstone National Park, attributed to the Yellowstone ‘Hotspot’, which because of the western moving North American Plate appears to be moving east and north. The Steens Basalts, covered much of the region’s southern most portion including Abert Rim, the Steens and Warner Mountain areas, built up layer upon layer to a depth of over 3,000′. In this southerly location faulting extended north from the Basin and Range region, that covers most of Nevada, which resulted in its horst and graben rise and fall. The 3,000’ tall escarpment that is Abert Rim, presents the exposed face of lavas from this group where they were thrust up, the adjacent Lake Abert dropping. The Warner Mountains formed in the same pattern. Steens Mountain, to its east, exhibits the same forces, only ‘reversing’ itself, its east facing escarpment rising a mile above the adjacent playa which is today’s Alvord Desert. At nearly 10,000′, its features are somewhat obscured by other faults in the broad lifted western slope and their consequent subsidence, as well as the carving of glaciers of the several cold cycles of the Ice Age. Later volcanic action from other area vents changed the area landscape.

On a scramble going up an ancient landslide on Abert Rim, looking north across Lake Abert to the alkalai flat to its north. The Rim a 30 miles long escarpment of Steens Mountain Basalt, lifted some 2’500′, located in the northern most portion of Basin and Range country.

While the CRBG flows built up north and east of most of Central Oregon, its impacts on the geography of the whole is profound building up the landscape to our north, affecting the flow of our rivers and the shaping of the Deschutes River Basin. Near the center of the above map of the CRBG you can see an irregularly curving ‘downward’ finger of lava which flowed south and east into the present day Prineville area, presumably following the Deschutes, then Crooked River Canyon upstream. From this map it is difficult to see the Caldera edge, how it made its way through the Smith Rock area.

The High Cascades, Building its Base Platform –

The HIgh Cascades, the eastern ‘strip’ which contain the dominate peaks of today, began forming their now high ‘base’ some 10 million years ago, lavas flowing from a series of fissures and faults likely as low silica, mafic, Pahoehoe, flood type lavas, much like the CRBG lavas. These formed a broad ‘platform’ like base. Beginning primarily as, relatively low ‘shield’ volcanoes, building in an additive way, one relatively thin layer after another, forming a broad, north-south running, ‘platform’ along the hundreds of vents. These massive shield volcanoes, forming along the Cascade Volcanic Arc, built up the ‘platform upon which the several major strato-volcanoes would much later form the well known peaks we see today.

The geology of the High Cascades was not a uniform process along the long north south Volcanic Arc. The broad base of Mt. Hood, swelled with the rising magma lifting the landscape through which the Columbia still carves its way. Base rock in the region can be seen bent into folds the strata lifted out of alignment from its more or less ‘level’ layers originally laid down. The Columbia River is the largest river in the world to cut through an active Volcanic Arc and it does so at near sea level elevation. Over millennia it has removed a massive amount of rock and soil. This ‘rising’ can be seen in the exposed strata of the Gorge and the canyons that cut across it between Mt. Hood and Mt. Adams. The consequent erosion and removal of burden above allowed the still active arc to lift the area. Mt. Jefferson, Hood, Adams and St. Helens, are ‘younger’ mountains in the Arc, and as such were subject to less glacial action over time retaining much more of their maximum form, than the older mountains that endured more cycles of the Ice Age and glacial ice. Many of the older peaks of the High Cascades to the south in Oregon were severely carved away by glacial ice like Mt. Thielsen.

The uplift of Green Ridge to Redmond’s west, was in response to the dropping of the Central Cascades graben, the large basement layer of crustal rock, about 3 million years ago. There are two primary parallel faults framing either side of the graben along which it drops. Two walls or ‘horsts’. Green Ridge, flanking it to the east, was thrust upward and presents as a ‘wall’ rising some 2,000′ above the flat bottom of the Metolius Valley, its eastern flank sloping more steeply than the landscape east out into the Deschutes Basin. The western horst, forms the western border along its fault, roughly delineating the far older West Cascades. Grabens tend to happen where the crust has thinned, or perhaps the supporting magma chamber has emptied to the point where it can’t support the load above, the drop further increased as lavas issuing from the many vents and fissures, flows on top adding to the weight. The above building of the broad base began after that, or was it coincident? A ‘graben’ is dense rock solidified from magma before it was ejected onto the surface, followed by lava flows from the fault (225 identifiable flows) occurring as the West Cascades eroded. The uplift of Green Ridge is associated with the Deschutes Formation the base of the Cascades ‘sinking’ under the additional load of accumulating volcanic deposition. The eastern flank of the Green Ridge uplift extends north and south emphasizing the slope down and away into the Deschutes River Basin. The Basin is framed to the east by the John Day Formation and the Ochocos. Later, the Newberry Volcano would nearly form a continuous southern boundary nearly cutting it off from the upper Deschutes River Basin, which a late Newberry flow actually did…briefly, before it was breached.

The uplift of Green Ridge to Redmond’s west, was in response to the dropping of the Central Cascades graben, the large basement layer of crustal rock, about 3 million years ago. There are two primary parallel faults framing either side of the graben along which it drops. Two walls or ‘horsts’. Green Ridge, flanking it to the east, was thrust upward and presents as a ‘wall’ rising some 2,000′ above the flat bottom of the Metolius Valley, its eastern flank sloping more steeply than the landscape east out into the Deschutes Basin. The western horst, forms the western border along its fault, roughly delineating the far older West Cascades. Grabens tend to happen where the crust has thinned, or perhaps the supporting magma chamber has emptied to the point where it can’t support the load above, the drop further increased as lavas issuing from the many vents and fissures, flows on top adding to the weight. The above building of the broad base began after that, or was it coincident? A ‘graben’ is dense rock solidified from magma before it was ejected onto the surface, followed by lava flows from the fault (225 identifiable flows) occurring as the West Cascades eroded. The uplift of Green Ridge is associated with the Deschutes Formation the base of the Cascades ‘sinking’ under the additional load of accumulating volcanic deposition. The eastern flank of the Green Ridge uplift extends north and south emphasizing the slope down and away into the Deschutes River Basin. The Basin is framed to the east by the John Day Formation and the Ochocos. Later, the Newberry Volcano would nearly form a continuous southern boundary nearly cutting it off from the upper Deschutes River Basin, which a late Newberry flow actually did…briefly, before it was breached.

The Deschutes Formation –

The Deschutes Formation has formed the surface features of much of our local landscape as we now know it. It includes multiple eruptive events and flows occurring in the Deschutes River Basin many up along the eastern flank of the High Cascades, including at least 78 statistically distinct explosive eruptions occurring between 6.25 and 5.45 Ma. Many of these flows, from sites like the uplifted Green Ridge, flowed easterly building up the landscape toward Gray Butte, Smith Rock, into and beyond Redmond and Bend, forming an ‘edge’ against which the Crooked and Deschutes Rivers flowed and eroded. These accumulated across the paleo and present day Deschutes River Basin greatly adding to its elevation and shaping its landform. These formed the ‘cap’ rock that underlies much of the immediate Redmond area and the fracturing, breaking rim of Dry Canyon, forming a basalt plain long before the river itself flowed here carving its way down. Select areas of west Redmond are overlain with multiple layers, including 40′-50′ of surface basaltic lavas. Some local areas were later overlain with flows from Newberry and of course sedimentation in low areas. Many later flows and eruptions continued occurring after the last glacial Ice Age period, inside of 20,000 years, such as those on MacKenzie Pass and around Belknap Crater which are less than a thousand years old. https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/abs/pii/S0377027321000226

Numerous small buttes remain in the Deschutes River Basin which were at one time cones or broad low shield volcanos, producing ash flows and surface lavas, standing above later flow basalts and ash flows that spilled from many vents and smaller fissures on the eastern flank of the High Cascades accounting for the slope of the Basin floor.

Cline Buttes, 7 miles west of Redmond and above the present Deschutes River Canyon, was one of the larger and eastern most vents of the Cascade Volcanic Arc, producing rhyolite flows 6 million years ago. These rhyolitic lavas were very viscous forced from these particular vents and so covered a relatively small area. The Buttes are eroded considerably down from their original elevation although they weren’t high enough to be glaciated and so lack evidence of the ‘carving’ done by glacial ice during the cyclic Glacial Ice periods.

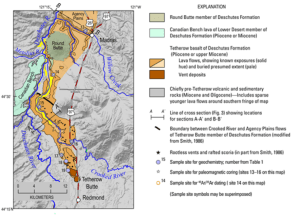

Tetherow Buttes Basalt – 5.3 million.

Popularly known as ‘Cinder Butte’ immediately north of Redmond, from which red cinder has long been mined, is one of the leftovers of the older Tetherow Buttes which produced large lava flows. These followed the paleo-Deschutes River (paleo- referring to the channel/canyon in which the river once flowed prior to the present day.) filling it at least in part, narrowly. The eruption and formation of the buttes/vents themselves served as a ‘blockage’ in the Deschutes Basin forcing the paleo-Deschutes to flow east of it to where the Crooked River joined it in the Smith Rock area, but not in its present canyon. The Crooked River would be forced north to its present position by an early and massive flow from the Newberry Volcano Complex south of Bend. But the Newberry flow was almost 5 million years after the Tetherow Buttes Basalt (More on it later.) Most of the Tetherow flow made its way into the nearby Deschutes Canyon to their north. Keep in mind that even after the Tetherow Basalt Flow the paleo-Deschutes flowed east of present day Redmond, and the Tetherow Vents, coursing around the south side of Smith Rock and the channel of the present day Crooked River very near where it is crossed by today’s Hwy 97…and it did so for almost 5 million years carving the remnant canyon rim. The Tetherow Basalt is the rock underlying the farm land immediately north of the Buttes, adjacent to and west of the town of Terrebonne. (Terrebonne itself, sits upon one of the early Newberry flows, again that occurred much later.) The flow followed the generally downward trending slope north following and filling the paleo-Deschutes Canyon making its way all of the way to the Columbia River. This flow is one of the longest single lava flows in the PNW. As commonly occurs the river channel, the canyon, filled with lavas, overtopping lower adjacent areas along the way. The flows occurred at a relatively high rate of speed due to both the slope, the lava’s temperature and low viscosity, rapidly reaching the Columbia. The discovery of this is a relatively recent one because of the narrowness of the flow and the erosive force of the Deschutes River which has been eroding it away ever since. Much of the Tetherow Basalt has been worn much away leaving isolated ‘patches’ of basalt to confound geologists.

A flood basalt like this emerges at over 2,080ºF moving rapidly as it cools down to about 1,800ºF. A flow cools most quickly at its exposed surfaces and where it contacts the ground. The deeper the flow, the more material and heat it contains, the further it can travel. The canyon, by containing the flow, by preventing its broad spread, contributed to its rapid movement to the Columbia river. In those places where it ‘escaped’ the canyon, the lava would have more quickly cooled and been rather limited in its spread, as is the case shown on the accompanying map. (As Hwy 26 begins to drop into the Canyon above Warm Springs from the east the Tetherow basalt can be measured at 45 meters thick.)

A flood basalt like this emerges at over 2,080ºF moving rapidly as it cools down to about 1,800ºF. A flow cools most quickly at its exposed surfaces and where it contacts the ground. The deeper the flow, the more material and heat it contains, the further it can travel. The canyon, by containing the flow, by preventing its broad spread, contributed to its rapid movement to the Columbia river. In those places where it ‘escaped’ the canyon, the lava would have more quickly cooled and been rather limited in its spread, as is the case shown on the accompanying map. (As Hwy 26 begins to drop into the Canyon above Warm Springs from the east the Tetherow basalt can be measured at 45 meters thick.)

The displaced river would have been forced elsewhere or, finding a more fragile seam between the old canyon wall and the new hardened material, found a way through and began the canyon cutting process again.

The Dalles Formation –

Dated to between 5.3 to 2.6 million years ago the Dalles Formation consists primarily of eroded sediments as much as 800’ thick across north central Oregon as far south as the Madras Basin, through which the Deschutes River carved its way to the Columbia, clearly evident in the layers exposed in the Canyons at Cove Palisades State Park and again as Hwy 26 descends to Warm Springs in the Deschutes Canyon. The Madras Basin area is underlaid with rock from the Clarno Formation and was formed relatively free of flood basalts, as a result of relatively little volcanic activity in the immediate area during this period, lying as it does largely outside of the region covered by the Deschutes Formation.

With the Cascades to its west, the Metolius River was forced north by the uplift of Green Ridge, turning abruptly east where it collides with The Dalles Formation following the downward sloping flanks of the Cascades on to the Deschutes River near its confluence with the Crooked River, deep within their confining canyons.

Round Butte, a small shield volcano just south and west of Madras, is associated with the late Deschutes Formation around 3 million years ago, contributing lavas that over topped all previous depositions. These are the rimrock basalts that ‘cap’ the rim above Cove Palisades State Park and Lake Billy Chinook, those of the far larger Tetherow Flow beneath it.

The Ice Age and the Last Glacial Maximum

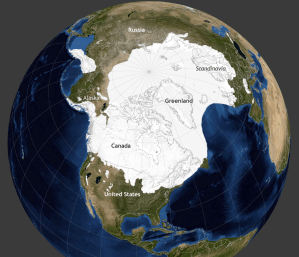

The Ice Ages began playing out here 2.6 million years ago, a phenomenon which is understood to still be in effect. Over this period the Earth’s climate has cycled from warmer to cooler and back again several times. We are still in the latest warming period which began an estimated 11,700 years ago following the Last Glacial Period which extended back 115,000 years. (Something to think about, the glacial period lasting ten times as long as the ‘warm’ periods.) During Glacial Periods the ‘permanent’ ice cap extends toward the equator as average temperatures around the Earth fall. The ice layers, remaining during the cooler Earth summers, built up to incredible depths, burdening the land under their incredible weight. The Last Glacial Maximum Period was reached about 20,000 years ago. I know, there’s a discrepancy between these dates. At that time the level of the oceans had dropped 400’ below present levels its waters bound up in Glacial Ice. 8% of Earth was covered in glacial ice, 25% of its land surface was so covered.

Glacial Ice is that which doe not melt from year to year accumulating over the centuries. Today glacial ice covers 3% of the Earth’s surface and about 11% of its land area. It is estimated that if the remaining glacial ice melts, due to man imposed climate change, that the oceans will rise another 230’. During the last Glacial Maximum, between 26,000 to 13,000 years ago, the ice extended south to approximately 45º North, roughly our own latitude, a line that varied with topography and broad climate patterns around the globe. True then as it is now the oceans moderate temperature extremes, the sustained cold reaching further south across the interiors of the larger continents. Here in the PNW glacial ice extended down through the Puget Trough in present day Washington reaching as much as 2 to 2.5 miles thick. It did not, however, extend down into central Oregon. It did not carve away our local landscape. The relative cold did greatly effect our local plant communities which would have likely resembled the northern boreal forest more than it does our present sagebrush steppe, with average temperatures lower and moisture levels somewhat higher.

Ice, of course, often covered mountains far to the south of 45ºN due to their elevation and ‘carved’ away at them. This included many of Oregon’s ‘older’ High Cascade peaks like Broken Top and Mt. Thielsen which would have experienced several glacial cycles. Other, older, mountain ranges like the Wallowas and the Blues with their far older and denser rock, display evidence of the ice’s carving in their typical curved valleys and moraines which are the remains of such actions physically pushed to the point where the glacier began to recede. Some mountains contain hanging cirques, bowl like structures carved out from the mountainsides opening out on slopes and valleys far below their mouthes. Steens Mountain although a product of the more recent Columbia River Basalt Group volcanism exhibit the power of glacial ice with its massively carved Kiger, Little Blitzen and Big Indian Gorges.

The rock of our dominant Cascade stratovolcanoes is much less dense than the hard rock of the Wallowas and Blue mountains and more susceptible to its power than Steens Mountain a product itself of the more dense and massive basalt flows of the CRBG. The Cascades are products of varied volcanic action with explosive falls formed from blasted, less dense, rock filled with gas pockets and vacuoles, created by escaping gases and trapped within the rapidly solidifying ejected rock, deposited around these vents, the bigger and heavier nearer, highly erodible, sometimes alternating with thick, clinkered flows while others were far less viscous capping and ‘gluing’ base material together. Overall these Cascade stratovolcanoes are much more susceptible to erosion of all types. Porous, water seeps in, freezes and splits them apart. On many of these volcanic mountains the hardest rock is within the mountain’s core where magma cooled and solidified over more time allowing the gases to escape, the remaining rock denser and more resistant to erosion.

The weight of hundreds, even thousands of feet of ice above, its hardness and gravity, slowly draws the ice downslope, carving away at the rock, grinding it ever finer as it pushes it along. The ice, its incredible weight, can cause the the land beneath to ‘sink’ into the mantle, deforming the crustal surface, channelling whatever melt water that does form to flow away beneath it adding its own erosive effect. This underlying deformed landform similarly directed the massive and periodic flow of the several Missoula Floods which swept away so much of the rock and soils of eastern Washington, gouging out the Columbia River Gorge to near sea level, drawing the flow the Deschutes River at increasing velocity contributing to its erosive power. And of course, as the ice melted and retreated during ‘warm’ periods, back toward the poles, the land ‘springing’ back up.

The pic right shows the extent of the Last Glacial Maximum in white. Much of Alaska was not covered due to persistent weather patterns that left it ‘dry’ grassland, as was much of the land of central and eastern Siberia, which supported several larger mammalian species now extinct or nearly so, animals like the Wooly Mammoth and Musk Oxen. Scientists use ice cores as well as cores obtained by boring into the ground to determine what types of plants grew on any given place over time. Pollen, which is physically incredibly durable, can remain intact and identifiable in these cores even back several million years. This allows palynologists, pollen scientists, to identify what grew in a place buried in the layers and date them. Additionally, ice cores reveal the gaseous makeup of the atmosphere at the time of its formation, the composition of which has changed with the geology and life that inhabits the earth.

The pic right shows the extent of the Last Glacial Maximum in white. Much of Alaska was not covered due to persistent weather patterns that left it ‘dry’ grassland, as was much of the land of central and eastern Siberia, which supported several larger mammalian species now extinct or nearly so, animals like the Wooly Mammoth and Musk Oxen. Scientists use ice cores as well as cores obtained by boring into the ground to determine what types of plants grew on any given place over time. Pollen, which is physically incredibly durable, can remain intact and identifiable in these cores even back several million years. This allows palynologists, pollen scientists, to identify what grew in a place buried in the layers and date them. Additionally, ice cores reveal the gaseous makeup of the atmosphere at the time of its formation, the composition of which has changed with the geology and life that inhabits the earth.

With the cyclic cooling, growth and advancement of the polar ice sheets came the associated cooling of adjacent landscapes. Between 129,000 and 11,700 years ago huge lakes formed in southeast Oregon, the so called Outback Country. Cooler temperatures brought with them lower rates of evaporation and so lakes tend to persist. Far southeastern Oregon is the northern extreme of the Great Basin region from which no rivers drain to the ocean. Rain and snowfall, glacial ice melt, whatever collects there, stays. Oregon was also going through a wetter phase at this time allowing the formation of massive lakes in the isolated basins, their various depth rising and falling, with their varying precipitation levels, most reaching their maximum depths 17,000 to 20,000 years ago. Many of these have long since dried and remain as wide flat playas, accumulating enough water in the odd wet period to form very shallow broad pluvial ‘lakes’, although often a wet period results only in the formation of mud. These ancient lakes included Lake Malheur, Lake Alvord, Lake Abert and Lake Fort Rock. Only a few remnants remain.

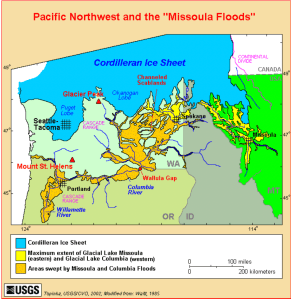

Missoula Floods –

This is the largest known glacial ‘erratic’ found in the Willamette Valley, a 70 ton hunk of granite swept along by the floods from its origin in Montana and deposited here, above the Valley floor.

The Missoula Floods occurred between 15,000 and 13,000 years ago with the advancement of the last warming period of our current Glacial cycle. As the polar ice began melting it accumulated behind massive ice dams to the east of present day Washington state, trapped between the remaining ice and the Rocky Mountains to its east. Gravity will always win out. The floods occurred an estimated 25 times over that period and did so catastrophically. Many cubic miles of water would be released at these times in a matter of a few hours. Transforming the landscape of Washington state east of the Cascades, scouring away loose soil and carrying multi-ton boulders at its peak flows, taking with it anything living in its path, plant and animal, necessitating its repopulation from protected, nearby, higher elevation, refuges. Much more recently, estimated to have occurred around 1450, was the Bonneville Landslide which formed the Bridge of the Gods, an event witnessed by local indigenous people and passed along in their oral histories. The slide completely blocked the Columbia until its flow eventually breeched and swept it away. The slide took with it the southern face of Washington’s Table Mountain a part of the blocking Cascade Volcanic Arc.

The Missoula Floods occurred between 15,000 and 13,000 years ago with the advancement of the last warming period of our current Glacial cycle. As the polar ice began melting it accumulated behind massive ice dams to the east of present day Washington state, trapped between the remaining ice and the Rocky Mountains to its east. Gravity will always win out. The floods occurred an estimated 25 times over that period and did so catastrophically. Many cubic miles of water would be released at these times in a matter of a few hours. Transforming the landscape of Washington state east of the Cascades, scouring away loose soil and carrying multi-ton boulders at its peak flows, taking with it anything living in its path, plant and animal, necessitating its repopulation from protected, nearby, higher elevation, refuges. Much more recently, estimated to have occurred around 1450, was the Bonneville Landslide which formed the Bridge of the Gods, an event witnessed by local indigenous people and passed along in their oral histories. The slide completely blocked the Columbia until its flow eventually breeched and swept it away. The slide took with it the southern face of Washington’s Table Mountain a part of the blocking Cascade Volcanic Arc.

Why include any of this? Without these floods augmenting the Columbia’s normal flow, the landform connecting Oregon and Washington’s Cascades and that of the entire ‘plateau’ to its east, would look radically different. The entire Columbia Basin, which includes our Deschutes, drains through the Gorge’s relatively narrow and deep channel. In the location of the Columbia Gorge the river found a ‘weak’ spot, and maintained it, wearing it away consistently over the many millions of years of ‘building’ the interior as the landscape lifted above the former sea floor. North and south of the Columbia’s western flow through its gorge the landscape rises, the Deschutes River, maybe 100’ above sea level at its confluence with the Columbia, rises 3,500’ as you follow it south to Bend, the landscape, continuing to rise as you go south to as high as 4,572’ at the top of the Spring Creek Grade, near mile post 241, and continues the trend into northern California, reaching 5,202’ at Mt. Hebron north and west of Mt. Shasta, a continuation of the Cascade Volcanic Arc. Through it also flows the Snake River from the higher east and west Snake River Plains country of Idaho. The Columbia River shaped the Cascades from early on to maintain this drainage path for the entire basin and in doing this created a landscape unique on earth. And, as a basin, its drainage converging on the Columbia has determined the overall land form between mountain ranges, the depth of the Columbia drawing the gravity driven flow of rivers and streams at a rate powerful enough to do so, wearing down the canyons and drawing sediments at a rate higher than it would were the Gorge shallower. The elevation change, the grade, the fall of the region’s rivers, power the erosive forces. Visiting the many playa of the Great Basin country without any ocean trending rivers to add their power to erosion, emphasizes this important feature. Endorheic basins, those without outlet, form broad, uniformly flat landscapes, locally contained and isolated. The Columbia and contributing Deschutes River Basin powerfully demonstrate the erosive power of water and its ability to shape a landscape…even as ‘arid’ as the eastside landscapes are. Our several mountain ranges are still able to ‘squeeze’ enough water from the depleted clouds above them of enough water to do so. A more uniform landscape such as the immediate Redmond area’s would be unable to do so and our world would be vastly different, more like that of far southeastern Oregon. Our lives are dependent upon our mountains and the forces that drive them through time.

[The Gorge also plays a significant role in the region’s weather, serving as an escape valve, high pressure air systems moving the atmosphere, with moisture and heat, back and forth, channeling the wind, effecting the region’s high and low temperatures, creating and relieving temperature inversions with their stagnant air masses, fog and hoar frost. That the Columbia River ‘found’ a way through the Cascades seems a certainty. Were it not in its present location it would have found another ‘weak’ spot somewhere else given the volume of water collecting in the interior.]

Over the Pleistocene, as glacial ice advanced and retreated, the life that could move did so following the retreat and advancement of temperate conditions which drove the ice. The ice cap followed these conditions, lagging slightly, in geological terms, behind, while contributing directly to those conditions themselves, the expanding ice cap reflecting away the sun’s radiant energy intensifying the cold and delaying the later warming. The advance and retreat of polar ice, with its accompanying rising and falling ocean levels, drew early people’s from Asia to North America. At the same time long established biotic communities ‘moved’ in response to these changes of climate. ‘Moved’ at a rate within generational limits, trees and plants moving at a rate at which they could advance, establish, mature and reproduce at a community scale. Intact communities. Spreading over time while establishing necessary supportive conditions. Unlike our present day technologically supported rate of change and spread, which is too fast for ‘unsupported’ plant and animal communities, we humans can simply pick up and leave to presumably supportive conditions elsewhere even when supportive conditions are absent through which we move. Plants can’t do this. At such artificially fast rates of change and spread, many species are lost. Communities spread as intact wholes. Glacial Periods, of the Ice Age, effectively ‘pinched’ organisms into a narrowing band around the equator, sometimes leaving remnant or relict populations behind, saved in favorable pockets or stranded unable to make the ‘jump’ to a landscape with more hospitable conditions, eventually causing at least some of these relicts to die out.

One successful mover has been Quercus garryana, the Oregon White Oak moving in a pattern of call and response south toward California, west of the Old Cascades as the cold and ice advanced, then returning, expanding north into southern British Columbia, as the ice retreated. I include it here because it is a favorite, but also because it is an iconic member of the Willamette Valley, the Puget Trough and a notable remnant occurring east through Columbia Gorge. This advance and retreat of the ice is reflected in the movement of this Oak. The Missoula Floods working with the erosive power of the Columbia River itself kept this eastern passage open for the ‘flow’ of plants and animals back and forth in coordination with the ice, without which many species could have been stranded and died, later being unable to return across a more formidable barrier of the Cascades. As one moves today through the Gorge and north and south up the eastern flank of the Cascades, one finds species that could not exist were the Gorge not there, nor even if the Cascade barrier backed the Columbia up behind a higher ‘exit’ elevation. Imagine if the breach through the Cascades backed the Columbia up to 1,000’-2,000’ elevation, to an elevation closer to the framing halves of the higher plateau. This would still allow the river to reach the Pacific, but it would likely prohibit the movement of many plants found commonly there today. Of course some would still make it, but the species richness would be reduced. The Columbia River ground its way through the massive flows and volcanic ‘lifting’ of the Cascade Volcanic Arc and the layering of Columbia River Basalts. The floods scoured away much of the overtopping soil and rock of Eastern Washington, finding the ‘soft’ spots and following the ‘edge’ of the numerous Columbia River Basalt Group flows and the sliding faults below. The Gorge did not ‘happen’ accidentally. Its existence continues to serve as a passageway for animals and plants, across the Cascade Volcanic Arc, allowing them to move back and forth, at their own ‘pace’ and at an elevation near that of present day sea level. The Garry Oak can still be found as far east as the gullies and draws around The Dalles, Oregon, with populations climbing the framing Gorge, broadening out as you move west where they climb the ‘wetter’ eastern flanks of Mt. Hood and Mt. Adams, then on further into select, supportive areas, north and south to beyond Yakima and down into protected reaches around Oregon’s Wamic area and further south into the Mutton Mountains of Oregon’s Warm Springs Reservation.

Here too the cold winter continental air can drain out, and be supplanted by wetter, west side air which serves to moderate Gorge conditions while at the same time, it sometimes paradoxically, mixes otherwise stagnant air in the Portland area staving off winter freezing extremes. It enables multiple processes influencing both sides. Geography both provides the supportive conditions life requires as well as serving as a limit and barrier to the movement of species and the variability of the local climate. Were the Gorge not here, life would be very different on the dry, east side.