Cascade Volcanic Arc –

Over the last 2.5 million years, roughly corresponding with the Pleistocene Ice Age, there have been at least 1,054 volcanoes in a ‘belt’ from Mt. Hood running 210 miles south to the California border and then, after a break, continuing to Mt. Shasta and Mt. Lassen, in a band 16 to 31 miles in width. These latter two, southern most of the Cascades, show no effect of glaciation from Glacial Periods. They were far enough south of the Glacial Ice to be unaffected. The material ejected and flowing from these many volcanoes and vents come from the crustal material of the subducting Juan de Fuca plate. The Cascades are a defining feature of our region in terms of aesthetics, but also as a shaper of climate, as well as being a physical barrier limiting the movement of organisms and thus goes to determining the ‘shape’ of our lives here. The Arc is still active, magma is still being ‘delivered’, building incredible pressure below through these same processes which have shaped this place to date. While we may assess its various mountains as ‘active’ or not, the volcanic arc, is still very much a factor in determining our long term future. Where it will next erupt from, and what form that will take, is impossible to say within any degree of confidence. But the earth’s tectonic plates are still in movement. Magama is still slowly, but inexorably, coursing through its crustal layers and the movement and pressures will continue to result in further eruptions.

Over the last 2.5 million years, roughly corresponding with the Pleistocene Ice Age, there have been at least 1,054 volcanoes in a ‘belt’ from Mt. Hood running 210 miles south to the California border and then, after a break, continuing to Mt. Shasta and Mt. Lassen, in a band 16 to 31 miles in width. These latter two, southern most of the Cascades, show no effect of glaciation from Glacial Periods. They were far enough south of the Glacial Ice to be unaffected. The material ejected and flowing from these many volcanoes and vents come from the crustal material of the subducting Juan de Fuca plate. The Cascades are a defining feature of our region in terms of aesthetics, but also as a shaper of climate, as well as being a physical barrier limiting the movement of organisms and thus goes to determining the ‘shape’ of our lives here. The Arc is still active, magma is still being ‘delivered’, building incredible pressure below through these same processes which have shaped this place to date. While we may assess its various mountains as ‘active’ or not, the volcanic arc, is still very much a factor in determining our long term future. Where it will next erupt from, and what form that will take, is impossible to say within any degree of confidence. But the earth’s tectonic plates are still in movement. Magama is still slowly, but inexorably, coursing through its crustal layers and the movement and pressures will continue to result in further eruptions.

Formation of the Central Oregon High Cascades:

The grouping of Broken Top and the Three Sisters began approximately 400,000 years ago as shield volcanoes building a relatively broad base before later forming their cone structures on top. (These shield volcanoes were roughly contemporaneous with the development of the Newberry Volcano 35 miles to their southeast.) There seems to be some discrepancies in our understanding of this area’s unfolding as some date it older, merging the time of shield building and the later stratovolcanoes. One source says that there were at least four massive and explosive events that buried much of the immediate area to Bend and Sisters in a pyroclastic flow, which would have solidified into tuff and massive ash falls, resulting in accumulations of pumice as much as 40’+, easterly and on to Bend. Broken Top is believed to be the first, the oldest, of these stratovolcanoes and has been most reduced by explosive eruptions and the periodic glacial action of the several cycles of the Ice Age. The North Sister’s tall cone structure, is a stratovolcano cone which formed 70-55,000 years ago, Middle and South Sister are ‘younger’. Volcanic mountains such as these don’t have a definitive ‘birth’ date as they are the result of long geological processes including periods of building, glacial action and erosion which often overlap with building phases: Mt. Jefferson (began about 1 million years ago, finishing its current ‘cone’ 55,000 years ago) and Hood began 500,000; all within the last million years. Oregon’s northern peaks are thought to be older than the central High Cascades. Many, once much larger southern peaks of the High Cascades, were severely reduced by glacial action of the several glacial Ice Age periods. (Mt. Mazama, whose collapse created Crater Lake, is far younger.)

These taller stratovolcanoes are the result of explosive volcanic ejecta, lava and pyroclastic flows. The ejecta, thrown into the area tends to settle around the core, the largest, heaviest, accumulating nearest by in a relatively ‘loose’ structure, subject to more rapid erosion. Later lava and pyroclastic flows sometimes occurred which tended to solidify, ‘glue’, these into more coherent and integrated wholes. The center of volcanic mountains tend to contain harder/denser material as a result of slower cooling, which allow gases contained in the magma to escape. This denser, then tends to remain as ‘plugs’ long after ‘softer’ material has eroded away.

Black Butte, just north of the town of Sisters, is 450,000 years old, and blocks the ‘valley’ between the Green Ridge uplift and the descending eastern flank of the Cascades directing the spring fed Metolius River north before it flows east to the Deschutes at Lake Billy Chinook and those south of Black Butte into the Whychus Creek drainage. Black Butte, at 6,347′, stands prominently west of Redmond. It is suggested that it was far enough east of the crest that it is in the rain shadow, receiving significantly less snowfall and build up of ice so has suffered no erosive glaciation.

The Cutting of Dry Canyon and the Newberry Volcano

[This is the portion of this effort which drew me initially to this project.]

[This is the portion of this effort which drew me initially to this project.]

45 miles south of Redmond, is the Newberry Volcano. I can see it from my house, arcing low across the horizon on clear days. It began building 400,000 years ago along with the ‘modern’ central Oregon High Cascades, Its last eruption, the Obsidian Flow, is entirely contained within its caldera, an event that occurred 1,300 years ago. It is still active, releasing gases, its heat rising from its buried magma chamber, along with surface movements, monitored by the USGS. Newberry’s many flows stretch approximately 75 miles north to south and 27 miles east to west, forming a shield volcano, an eastern outlier of the Cascade Volcanic Arc, with its extensive system of vents and apron of lava flows. The Newberry complex of vents cover almost 1,200 square miles, an area about the size of the State of Rhode Island, making it the largest volcano of the Cascades volcanic chain. Newberry includes 400 different ‘vents’, which all erupted various materials, including Pilot and Lava Buttes, in and near Bend, the latter of which produced a lava flow that blocked the Deschutes River, around 7,000 years ago, south of present day Bend, forming a huge lake which eventually breached the blocking flow at the Dillon Falls site. The same lava flow forms the river’s eastern edge as it flowed toward Bend.

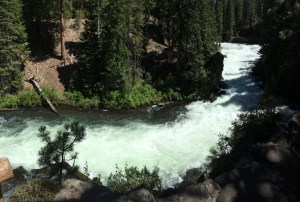

The tumbling Deschutes River flowing through Dillion Falls between the 7,000 year old Lava Butte flow and the several million year old flow I took this picture from.

The Deschutes River once flowed east of Bend’s Pilot Butte and east of Redmond’s location, reaching the Crooked River at Smith Rock. The Deschutes River Basin, within which Redmond and Bend lie, is the result of volcanic ‘building projects’ to our east, as noted above, and to the west as a result of the rise of the West and High Cascades along with the flows of the Deschutes Formation along the Cascades eastern flank, raising the terrain and ‘pushing’ the river east. Collectively, the volcanics of the east and west, and deposits of eroded sediments, lifted the basin shifting the course of the river and its tributaries creating a shifting north south ‘seam’ into which this Deschutes was forced.. Newberry, and Mazama to its south, were key later players in this riverine ‘drama’.

A lava flow 400,000 years ago from the Newberry Volcano overtops the ‘Smith Rock’ ash flows that were expelled millions of years earlier after the collapse of the Crooked River Caldera, while also overtopping and abutting various other earlier area flows of the Deschutes Formation. This earlier of Newberry flow, known as the Crooked River Gorge Flow, is visible to the south of Smith Rock. It blocked and pushed the paleo-Deschutes River back west where it would carve the channel that would become Redmond’s Dry Canyon. The actual diversion point where it was forced from its earlier canyon isn’t known as it is buried underneath. The same flow filled the canyon of the Crooked River in places forcing it northward, within the canyon, downstream to well beyond the Peter Skene Ogden Wayside and the Hwy 97 bridge, all of the way to present day Cove Palisades State Park. This is an example of the ‘intra-canyon’ basalts that filled portions of earlier canyons across the region. Water flows down hill so the altered Deschutes found a new more westerly route, following the general slope of the Basin northward. Forced from its previous channel the river would have been moved west along the expanding edge of the lava flow and then continued on following the general grade north across the river basin, to where it nearly intersected the remains of Tetherow Buttes at the north end of Redmond following the contours around them.

(The figures show a more detailed ‘story’ of these collective flows as they followed various canyons filling low spots and basins shifting Tumalo Creek as well to the west of Redmond. Evidence of this should be visible at the site of Cline Falls State Park. Piecing this together from many sources requires a bit of mental gymnastics. The Oregon State geologic map at the start of this post, is helpful, but one must keep in mind that it is a ‘surface’ map that cannot describe the many underlying layers nor those that have been eroded away.)

This pattern of the Deschutes continued until 75,000 years ago when the Basalt of Bend, which issued from vents on the north slope of Newberry, blocked this version of the Deschutes again, pushing it further west into Tumalo Creek in the Bend vicinity. This diversion began south of Pilot Butte forcing the river from its former channel into its present day course between the Basalt of Bend flow and Awbrey Butte, a small basaltic shield volcano of the Deschutes Formation, the river following this lava flow’s ‘new’ edge. (Awbrey formed atop several late ash flows and falls of the Deschutes Formation.) This is also the period when the Newberry Volcano explosively collapsed forming its caldera.

This pattern of the Deschutes continued until 75,000 years ago when the Basalt of Bend, which issued from vents on the north slope of Newberry, blocked this version of the Deschutes again, pushing it further west into Tumalo Creek in the Bend vicinity. This diversion began south of Pilot Butte forcing the river from its former channel into its present day course between the Basalt of Bend flow and Awbrey Butte, a small basaltic shield volcano of the Deschutes Formation, the river following this lava flow’s ‘new’ edge. (Awbrey formed atop several late ash flows and falls of the Deschutes Formation.) This is also the period when the Newberry Volcano explosively collapsed forming its caldera.

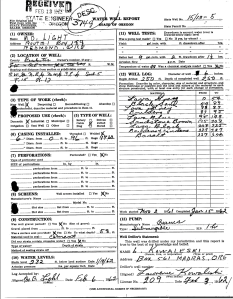

Over the 325,000 years that it flowed through present day Dry Canyon, the paleo-Deschutes cut its way down through the rock layers into the tuff of the Crooked River Caldera and the closely related Smith Rock Tuff which was a part of the same process. (The story of the geology of a place such as this is not linear and the data, the facts, subject to interpretation. The Tuff layers recorded in the well driller’s log here were not analyzed so that the precise vent of origin isn’t known. This could have come from ash flows of the Deschutes Formation. I could not find a definitive study. Such flows were, however, more common in the Bend area than here. So I stand by my ‘guess’.) At the City of Redmond’s well #9 position, just north of the Antler canyon crossing where the river had cut as much as 168’-198’ further down. The difference in the depth I note here is because of tuff and basalt layers sandwiched in at that point and the question of their origin and timing.

[The present landscape of the old Bend townsite and adjacent areas was highly affected by many later small lava, ash flows, ash falls and pumice falls from small nearby, eruptive centers less than a million years ago. Bend itself is cut by the present day Deschutes River leaving its canyon at the Old Mill Site before continuing on northward around Awbrey Butte in a canyon which again broadens out, briefly, in the Tumalo area before being quickly contained once again in a steep walled canyon. These pumice and ash falls are among several events known as the Desert Springs Tuff, Bend Pumice, Tumalo Tuff, and Shevlin Tuff flows and falls. The pumice falls were the result of more explosive events that sent ‘tephra’, the gas filled molten rock, into the air to rain down on surrounding land. Another distinguishing factor in the formation of pumice is that the molten material has a much higher silica content, where basalts tend to contain just over 50% silica and pumice over 70%. The flows were, again, pyroclastic flows of hot gases and mineral particulate. A few younger events topped some of these larger events, concealing their sources and have yet to be determined as they lie obscured beneath the build up of flows further up the flank of the Cascades.]

5+ million years ago, at the current well #9 location where Antler crosses the bottomland of Dry canyon, the surface stood above its present level, probably close to the surrounding area’s 3,000′ elevation as a result of the many flows of the Deschutes Formation. Between the Basalt of Crooked River Gorge, 400,000 years ago and 75,000 years ago, the paleo-Deschutes carved down through the layers to an elevation of around .2,830′, 170′ below its rim. With the latest Newberry flow, the Lava Top Butte Basalt, in the area 70,000 years ago it was filled to its approximate present level of 2,956′. It is impossible to say at what level it will be in the future.

The Basalt of Bend, of 78,000 years ago, and the Basalt of Lava Top Butte both combined to fill and obscure the canyon to the south of Quartz Ave. and Redmond. The Basalt of Bend, filled a broad area between Bend and Redmond, west to the river’s channel now near Tumalo.

The site of the Redmond Caves, lava tubes were supplied by volcanic vents on Newberry around 70,000 years ago. This scab land is characteristic of much of the landscape between Bend and Redmond with surface basalt and older Juniper on thin soil. The tubes sat atop the surface the outer edges, cooling and thickening, insulated the flowing lava inside allowing it to continue flowing on like a branching network of roots. Later, the tubes emptied of lava, sometimes collapsed where they couldn’t support themselves, creating openings like those at Redmond Caves. There are several ‘caves’ there scattered along their length with at least one on private property just north of Dry Canyon Park. So, evidently at least one tube runs beneath the surface somewhere.

70,000 years ago the Basalt of Lava Top Butte, one of the Newberry complex’s many vents, partially filled Dry Canyon with Pahoehoe type lava, mafic, lower silica content, less viscous, a more fluid form, delivering it via the Redmond Caves and the Horse lava tube system. Evidence of Pahoehoe lava on the canyon floor can be seen in multiple locations with its ‘ropey’ texture laying relatively flat and even with the surround floor. In other places, particularly at bends in the canyon, blocky forms are heaved up as the lava’s momentum lifted it up on itself, slowing and cooling enough here and there to form a chunky, blocky, surface. This flow continued down the old, paleo- Deschutes all of the way to Crooked River Ranch and further ‘downstream’ just beyond the dam of present day Lake Billy Chinook.

Crater Lake and Mazama’s Caldera –

The Little Deschutes River extends through the Deschutes basin to its southern most point, its origin on Mt. Theilsen at an elevation of 6,000′. This tributary of the Deschutes meanders below it and across the pumice plains north of Mt. Mazama for 105 miles before it joins the Deschutes at Sunriver. Mazama’s explosive eruption 7,700 years ago coveried much of the region to its north in a massive Pumice Fall, creating Crater Lake in the process. As much as 6’ of pumice covered Newberry itself, 75 miles north of Mazama, a layer that thinned out rapidly every mile north. The landscape around LaPine is largely defined by it where it fell filling basins and creating broad, large flats on which area Lodgepole Pine forest dominates.

These pumice falls went to determining many of our local soil conditions. Soils formed from earlier Deschutes Formation lava flows break down more quickly into soil sized particles forming finer textured soils relatively quickly, in geological terms, when compared to those of pumice. Pumice, having a much higher silica content, is harder, more glass like and slower to break down. These form the typically coarse, loose soils that thinly cover so much of the Juniper and Sagebrush Steppe country in the region, especially to our south. These pumice derived soils are subject to wind and water erosion and tend to be moved off of higher or exposed elevations, filling in depressions and basins which accounts for the variability in soils in the Redmond area which received less pumice from Mazama and the other closer and more recent events. The overtopping pumice soils also tend to slow the further breakdown of the older soils beneath them. All of this goes to effecting what plant communities will grow on them and how subject to erosion they will be with continuing disturbance of their surface.

Lava Butte Eruption and Lake Benham –

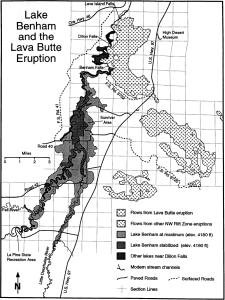

The last redirection of the Deschutes occurred around 7,000 years ago, when Lava Butte, adjacent to Hwy 97, one of Newberry’s vents along its Northwest Rift Zone, produced lava flows which formed temporary ‘dams’ along the Deschutes, in the Benham and Dillion Falls area, filling the canyon, in places, with over a 100′ thickness of basalt, while backing up the river which flooded the basin south into the Sunriver area and beyond to the LaPine Recreation Area before the river eventually breeched the blockage creating the present day falls. The ‘dam’ was estimated to have topped out at 4,180′ elevation before erosion began. This was thought to have been ‘quickly’ reduced to 4,160′ as the river scoured away the looser material on top. Sedimentation evidence, which occurs over time, suggests that it once inundated 15 sq.mi. of adjacent lands, upstream. The ‘Meadows’, at Sunriver are at 4,155′, soil surface of which is comprised of deposited sediments. Drilling records show that the original river channel was some 80′ deeper than the current elevation at Benham Falls.

The last redirection of the Deschutes occurred around 7,000 years ago, when Lava Butte, adjacent to Hwy 97, one of Newberry’s vents along its Northwest Rift Zone, produced lava flows which formed temporary ‘dams’ along the Deschutes, in the Benham and Dillion Falls area, filling the canyon, in places, with over a 100′ thickness of basalt, while backing up the river which flooded the basin south into the Sunriver area and beyond to the LaPine Recreation Area before the river eventually breeched the blockage creating the present day falls. The ‘dam’ was estimated to have topped out at 4,180′ elevation before erosion began. This was thought to have been ‘quickly’ reduced to 4,160′ as the river scoured away the looser material on top. Sedimentation evidence, which occurs over time, suggests that it once inundated 15 sq.mi. of adjacent lands, upstream. The ‘Meadows’, at Sunriver are at 4,155′, soil surface of which is comprised of deposited sediments. Drilling records show that the original river channel was some 80′ deeper than the current elevation at Benham Falls.

Deschutes Basin Mega Floods –

This is here as a place marker. In a conversation with geologist Danielle McKay, she’s told me of a paper that is to be coming out describing massive flood(s) of lesser power, but of similar effect to the Deschutes basin, that the Missoula Floods had on the Columbia, sweeping south to north…that’s it. No dates. I’m guessing that this would have been a similar situation, resulting from a glacial ice related event, released by the retreat of ice up the Cascades, from the most recent Glacial Maximum. This would date within the last 20,000 years, well after the formation of Newberry Volcano which creates a bit of a pinch point, in terms of stream flows. This would have been before the above described blockage 7,000 years ago, Glacial Ice capping the southern Cascades blocking the waters from the thawing ice. A dam comparable to the one that lead to the Missoula Floods, although much smaller, could have formed blocking the basin’s drainage as the warming began. The Newberry Volcano was in place well before this thaw, but because the Lava Butte lava flow wouldn’t occur for another 13,000 years, the ice dam would have had to be considerably broader. The Lava Butte flow is believed to have blocked the flow and drainage of the upper basin of the Deschutes before its later breaching itself, backing up a massive amount of water, but did it breach the blockage catastrophically at Benham Falls or was that a more gradual process? I’ll have to wait until I see the paper.

The Newberry Obsidian Flow and More ‘Recent’ Activity

East and Paulina Lakes, the Big Obsidian Flow, all contained within the Newberry Caldera, its rim in the background.

The Newberry obsidian flow, was contained within the caldera itself, covering only about 1 sq.mi., so it had no effect on the surrounding landscapes. It is Newberry’s, and the region’s, most recent flow occurring 1,300 years ago and is the nation’s fifth largest obsidian flow. Such flows are relatively high in silica, very thick, viscous and cooled quickly, all of which inhibit the formation of crystals within the lava, giving it it’s glass like character. There have been numerous other ‘small’ events over the last 10,000 years including those in the MacKenzie Pass area and one on the south east flank of the South Sister, as well as detectable heat below some of the Cascades, venting of gases even occasional slight uplifting of the ‘platform’ to the southwest of the South Sister, but nothing that suggests anything more in the lifetimes of we humans currently alive…just a reminder that there will be more.

Conclusions –

There is much more not covered here. The point of all of this is that the landscape is not ‘finished’, nor was it ‘created’ at a singular date, in fact no ‘part’ of the landscape is fixed or finished. All points are in various stages of formation and erosion. Dry Canyon’s landscape ‘story’ is linked to that of the region and all of the forces which continue in effect. One of the difficulties in learning the geologic history of this place is that the story is incomplete and ‘discoveries’ and interpretations are added over time, some of which corroborate our past understanding, while others, put the previous story to task and force us to consider a new one. Data is data, but how it is put together and what it can mean is subject to interpretation. This ‘problem’ pervades much of science, and always will, as our knowledge can always only be incomplete. The continental plates are continuously ‘shifting’. The layering of the earth’s crust, hides much from our view. Erosion continuously wears away bits of it, gradually amounting to entire mountains, carving deep canyons in others, burying everything lower in sediments, leaving the available record incomplete and fragmented. The stories we tell ourselves shape the decisions we make and how we live our lives in a place.

In a sense, the earth is ‘alive’. While it is not an ’organism’ as we have come to understand it, neither is it an inert rock on which our lives play out independently, separately. It is an incredibly complex system of a bewildering number of interlocking relationships that change over vast time periods and in moments. Its changes are responsive to the forces and resources in effect over time, much as is any organism. Those changed conditions go to its changed response, far beyond the physical layers of its crust.

From this comes the particular components and mix of atmospheric gases and bodies of water, enabling life, increasing the complexity of its expansive communities, the relationships between all of its parts, serving and enhancing them, linking them into a responsive and coherent system driven by the energy of the sun and those internal to the earth. Unlike individual organisms the earth cannot reproduce itself through cloning or sexual reproduction, but through the processes it possess, it works to permit and support life in all of its diversity, which serves to move the whole ‘ahead’. The natural selection of species is itself an outgrowth of this, of the larger adaptive system. While the ‘mechanics’ of its internal ‘engine’, its mass, mantle and core, its dynamic relationship with the sun, the sun’s continuous energetic contribution, all continue in a more or less robust relationship, ‘self-righting’ in a sense, within limits. The earth, and the life it supports, continues on in complementary relationship, in a bewildering system of feedback loops, which all go to moderating its countless ‘parts’.

It is a system of which we are a part and, as such, not entirely capable of seeing ourselves. We are not simply the individuals we tend to view ourselves as, independent free agents. We are a part of a much larger whole and live within its limits, both as ‘agents’ which effect the world around us and as integral parts of it, our lives, responsive to and largely shaped and determined by this world around us, a world in a perpetual state of change, self regulating. We may modify the local effects the earth system exerts upon us, but we are still bound by those limits. To ‘live’ outside of them, for any length of time, requires an expenditure energy and resources which are themselves limited. Because we lack the experience to fully see this, we are left with our imaginations, our curiosity and ability to consider the many bits and pieces. We can study and tell ourselves a comprehensible story and change our ‘behavior’ or response to this place. And, we should live in a state of wonder, respect and awe. Taking this world, this place and our lives in it for granted is a great sin that should be avoided. A loss for all.

There are many possible stories. When we consider them we must consider the story tellers intent. Is it to understand this world in which we live or does it serve a more selfish and limited human desire? Does it embrace the necessary complexity of this place in which we live or does it serve more limited human ends. Whatever it is, such a story has to address relationship. Neither this planet, nor we, are independent actors. All things effect all others…continuously.

5+ million years ago, at the current well #9 location, where Antler crosses over the bottomland of Dry canyon, the surface stood above its present level, probably close to the surrounding area’s 3,000′ elevation. By 75,000 years ago the paleo-Deschutes had carved down to a depth of around 2,775′, some 225′ below its rim. With the latest Newberry flow in the area 70,000 years ago it ‘filled’ to its approximate present level of 2,956′. It is impossible to say at what level it will be in the future.

The Basalt of Bend, and the Basalt of Lava Top Butte, both combined to fill and obscure the canyon to the south of Quartz Ave. The Basalt of Bend filled a broad area in the southern section of landscape north of Bend, west to the river’s channel now near Tumalo. Before these events, Dry Canyon, obscured beneath these two massive flows, still carried the paleo-Deschutes still flowed through a canyon to the east of Bend’s Pilot Butte, but where exactly would require hundreds or thousands of drill sites and analysis to determine. No evidence remains on the surface. The puzzle of all of this still remains to be assembled.

Appendices:

Elevations –

The elevations below are estimated from the USGS Redmond, Oregon 7.5 minute Topo Map. ER and WR are the elevations at the East and West Rims, approximations due to slopes and breaks in the rim. The downtown core is at or just above 3,000′.

Redmond Caves, from which the lava left the tube system to fill the Canyon floor, 3,040’. The lava likely exited from several points in this area to make tis way to the Canyon.

Current Canyon Floor at Quartz, 2,995’

Canyon Floor at Highland, 2,975’. ER- 2,990’

Canyon Floor at Antler, 2,956’ at well head ER- 2,985’

Floor elevation from the driller’s log)

Canyon Floor below West Rim Park, 2,930’. ER- 2,980’. WR- 2,960’

Canyon Floor at Maple 2,900’ ER- 2,960’ WR- 2,960’

Canyon Floor at Wastewater TP, 2,870’. ER- 2,940’. WR- 2,920’

Canyon Floor at Pershall, 2,860’ ER- 2,960’

The total fall of Dry Canyon Park’s bottomland from Quartz to Wastewater Treatment Plant, is 125’ over 3.75 mi. The path along which the mileage is measured is ‘extra’ curvy so I’m going to put the Park’s length at 3.5 miles. This makes the surface slope about 36′ per mile, which would be a large drop on any river, comparable to the drop at the Deschutes’ Whitehorse Rapids above Maupin. Due west of Quartz Park, the current Deschutes River runs along its canyon bottom at 2,880′ el. Due west of the wastewater treatment site within Dry Canyon, the Deschutes is at 2,730′ having dropped 150′ along the river, 20′ of which happens at Cline Falls. This is a lot of drop and this section of the river contains multiple rapids.

It is interesting to note that along the Lower Deschutes River, from Maupin to the Columbia, the river drops on average 13′ per mile. These local sections of Dry Canyon and the Deschutes River both exhibit much greater slopes. That the slope of Dry Canyon is as steep as it is may be related to the fact that its bottom surface is determined by a lava flow. Fluid, mafic lavas like this one are around 1000 times more viscous than water and so flow far more slowly, more ‘thickly’. This probably accounts for the ‘floor’ at Quartz being nearly at the surrounding grade, it being much closer to the lava’s ‘source’, where it exited the tubes, thus filling the old canyon completely, filling, obscuring, it. The east rim, along its length through Redmond exhibits a relatively uniform decline of elevation established by the collective flows of the Deschutes Formation around 5 million years ago. At the location of the wastewater treatment plant, the canyon’s bottom is around 90′ below the east rim. As you continue northwesterly the landscape opens more broadly, but continues dropping, the lava of the Lava Top Butte spreading our across the plain while still following the river’s shallower, obscured channel/canyon.

You can ‘play’ with these numbers endlessly and they will still have some validity. If one takes the conservative rate of fall found on the Lower Deschutes today of 13′ per mile and took as a starting point the elevation east of Pilot Butte, some 16+ miles away, considered possible curves in the paleo-Deschutes that earlier canyon could have been somewhere near 208′ deep as it approached the Redmond area. But of course there were other volcanic events occuring over the river’s formative period which could have ‘jockeyed’ it around to that it didn’t stay in one channel to have ever done this. Still, it is fun to speculate.

I looked at several drill logs in this areas, but was unable to discern the location of the canyon in its suspected northerly course. Maybe with more time and a greater ability to understand the descriptions noted in the logs….

US Topo 7.5-minute map for Redmond, OR, to see the current ‘lay of the land’.

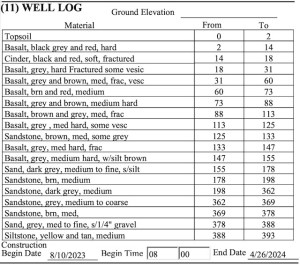

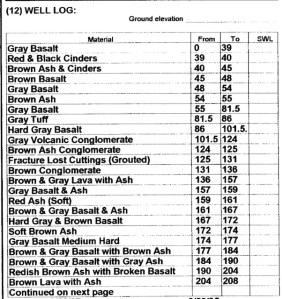

Selected Well Logs required by the state of Oregon.

I selected these as they are located within the Canyon itself. I was hoping to find definitive records of the 70,000 year old Lava Top Butte Flow, its depth as it partially filled Dry Canyon, to determine the depth of the canyon before being ‘filled’, but the ‘language’ used by the well drillers is a little hard to decipher. For example:

In the document dated March 1978, well number # 155/13E-5a, the driller refers to possibly two separate lava/basalt flows between 7′ and 37′, on top of a ‘yellow sandstone’, which I’m guessing is actually a thick ‘tuff’ layer, between the 37′-120′ levels, underlain with a scoria/cinder layer down to 170′. The tuff layer could be from the CRC/Smith Rock events. I was confused by the underlying cinder layer, thinking first that it was from later Tetherow eruptions which created the ‘cinder’ buttes that remain today above the surrounding grade…but this layer is below the tuff layer, which would be far older??? If it is actually ‘sandstone’ deposited as sediment from the eroding Cascades to the west, well then….

The well log for the new City of Redmond’s well #9, dated May 17, 2024, well # 143951 is discussed in the text above. This well is drilled in the canyon floor immediately north of the Antler Ave. street crossing. I found the graphic which is included above, but here are the drillers actual notes:

Then there is this log dated Mar. 27, 1998, well #L23805, at 19th and Quartz Ave., another municipal well at the south end of Dry Canyon Park.

This last log is from 1961 and is for a well drilled on the old Light’s Dairy property, a dairy my family used to buy raw milk from, and which was later sold, continuing on as a dairy to 2010 or later. My wife and I now live on a small piece of the property within the limits of the old dairy. It lies immediately south of Spruce St. approximately 1,500′ due west of the Canyon’s center at an elevation of 2,950′, 80′ above the Canyon floor at the Wastewater Treatment Plant, which is 2,870′. The well log shows a total depth here, of these upper basalt layers, of 198′ before piercing a 13′ layer of ‘brown sandstone’/tuff(?). Where exactly on the property, I don’t know, East-west there is considerable fall across the old dairy property, so the numbers could vary 10’ or better. If that is the same tuff layer that was found at the Antler well #9 site, and it covered the area uniformly this suggests a ‘basement’ level for the Canyon. All of the accumulating basalt above that tuff layer was likely contributed by Deschutes Formation period flows. This would mean that the Canyon’s original depth at the north end before the filling by the Lava Top Butte Flow, was 115′-125′ deeper than it is today, give or take. The total depth then at the Wastewater TP below the east rim would have been around 200′. This doesn’t take into account the possibility that the paleo-Deschutes may have eroded down through some of the tuff as well. If it did, then the Canyon was even deeper, I suppose a possibility given its width and the nearby comparable of the Crooked River Gorge at the Hwy 97 Scenic Wayside, with its depth of 328′ at the bridge crossing, which is 410′ across. In contrast the Maple street bridge is 780′ long with a current canyon depth filled to within 70′ or so of the east rim. Imagine it another 260′ deep! Fun factoids!!! Always subject to revision!

a total depth here, of these upper basalt layers, of 198′ before piercing a 13′ layer of ‘brown sandstone’/tuff(?). Where exactly on the property, I don’t know, East-west there is considerable fall across the old dairy property, so the numbers could vary 10’ or better. If that is the same tuff layer that was found at the Antler well #9 site, and it covered the area uniformly this suggests a ‘basement’ level for the Canyon. All of the accumulating basalt above that tuff layer was likely contributed by Deschutes Formation period flows. This would mean that the Canyon’s original depth at the north end before the filling by the Lava Top Butte Flow, was 115′-125′ deeper than it is today, give or take. The total depth then at the Wastewater TP below the east rim would have been around 200′. This doesn’t take into account the possibility that the paleo-Deschutes may have eroded down through some of the tuff as well. If it did, then the Canyon was even deeper, I suppose a possibility given its width and the nearby comparable of the Crooked River Gorge at the Hwy 97 Scenic Wayside, with its depth of 328′ at the bridge crossing, which is 410′ across. In contrast the Maple street bridge is 780′ long with a current canyon depth filled to within 70′ or so of the east rim. Imagine it another 260′ deep! Fun factoids!!! Always subject to revision!

Sources:

Books I’ve read to give me some broader understanding

Annals of the Former World, John McPhee, Farrar, Straus and Giroux, 1998. This was my initiation to the plate tectonics of North America. McPhee is not a geologist, but a great writer able to speak to the layman.

Oregon Geology, Sixth Edition, William N. Orr and Elizabeth L. Orr, OSU Press, 2012.

In Search of Ancient Oregon: A Geological and Natural History, Ellen Morris Bishop, Timber Press 2016.

Roadside Geology of Oregon, 2nd Ed., Marli B. Miller, Mountain Press, 2014

Geological Field Guides

A Field Guide to the Geology of Cove Palisades State Park and the Deschutes Basin in Central Oregon, ODGAMI, vol 52, num.1, January 1990. https://pubs.oregon.gov/dogami/og/OGv52n01.pdf

Guide to the Vents, Dikes, Stratigraphy, and Structure of the Columbia River Basalt Group, Eastern Oregon and Southeastern Washington, USGS 2017. https://pubs.usgs.gov/sir/2017/5022/n/sir20175022n.pdf

Field trip guide to the Oligocene Crooked River caldera: Central Oregon’s Supervolcano, Crook, Deschutes, and Jefferson Counties, Oregon, OREGON GEOLOGY, VOLUME 69, NUMBER 1, FALL 2009, https://people.wou.edu/~taylors/gs407rivers/McClaughry_etal_2009_CrookedRiverCaldera_DOGAMI.pdf

Field trip guide to the Neogene stratigraphy of the Lower Crooked Basin and the ancestral Crooked River, Crook County, Oregon, OREGON GEOLOGY, VOLUME 69, NUMBER 1, FALL 2009, https://pubs.oregon.gov/dogami/og/OGv69n01-Neogenestrat.pdf

Field-Trip Guide to the Geologic Highlights of Newberry Volcano, Oregon, USGS, 2017. https://pubs.usgs.gov/sir/2017/5022/j2/sir20175022j2.pdf

Field Trip Guide to the middle Eocene Wildcat Mountain Caldera, Ochoco National Forest, Crook County, Oregon. https://pubs.oregon.gov/dogami/og/OGv69n01-WildcatMountain.pdf

Hydrogeology of the Upper Deschutes Basin, Central Oregon: A Young Basin Adjacent to the Cascade Volcanic Arc, Field Guide to Geologic Processes in Cascadia: Oregon Department of Geology and Mineral Industries Special Paper 36, 2002. https://corpora.tika.apache.org/base/docs/govdocs1/390/390626.pdf

Papers and Sources on Related Specific Topics

GEOLOGY AND ORIGIN OF THE METOLIUS SPRINGS JEFFERSON COUNTY, OREGON, The Ore Bin, DOGMAI, vol 34, no. 3, March 1972. https://pubs.oregon.gov/dogami/og/OBv34n03.pdf

HIGH LAVA PLAINS, BROTHERS FAULT ZONE TO HARNEY BASIN, OREGON, USGS Circular 838; https://npshistory.com/publications/geology/circ/838/sec5.htm

Cascade Mountains https://people.wou.edu/~taylors/gs407rivers/Cascades.pdf

How the Cascades Formed; https://wa100.dnr.wa.gov/south-cascades/how-the-cascades-formed

A far-traveled basalt lava flow in north-central Oregon, USA. (Tetherow Buttes) GSA Bulletin, 2024. https://pubs.geoscienceworld.org/gsa/gsabulletin/article/136/7-8/3291/633458/A-far-traveled-basalt-lava-flow-in-north-central

Geologic Map of the Bend 30- × 60-Minute Quadrangle, Central Oregon, David R. Sherrod, Edward M. Taylor, Mark L. Ferns, William E. Scott, Richard M. Conrey, and Gary A. Smith, USGS 2004; https://pubs.usgs.gov/imap/i2683/i2683_bend_pamphlet.pdf

General Geologic Setting of the Cascade Region: http://npshistory.com/publications/geology/state/or/diamond_lake_geology/sec2.htm

Interactive Geologic Map of Oregon, Oregon Department of Geology and Mineral Industries: https://gis.dogami.oregon.gov/maps/geologicmap/

Lava Butte Eruption and Lake Benham, Robert Jensen and Lawerence Chitwood.

The magmatic origin of the Columbia River Gorge, USA, SCIENCE ADVANCES, 20 Dec 2023,Vol 9, Issue 51, https://www.science.org/doi/10.1126/sciadv.adj3357

Mesozoic collision and accretion of oceanic terranes in the Blue Mountains province of northeastern Oregon: New insights from the stratigraphic record, Rebecca J. Dorsey and Todd A. LaMaskin, Arizona Geological Society Digest 22 2008; https://pages.uoregon.edu/rdorsey/Downloads/Dorsey&LaMaskin2008.pdf

GEOLOGY AND ORIGIN OF THE METOLIUS SPRINGS JEFFERSON COUNTY, OREGON. The ORE BIN Volume 34, No.3 March 1972, https://pubs.oregon.gov/dogami/og/OBv34n03.pdf

Newberry Volcano—Central Oregon’s Sleeping Giant, U.S. GEOLOGICAL SURVEY and the U.S. FOREST SERVICE; https://pubs.usgs.gov/fs/2011/3145/fs2011-3145.pdf

Oregon’s geologic history. A new cross-section and timeline –and some great places to see it. https://geologictimepics.com/2021/03/02/oregons-geologic-history-a-new-cross-section-and-timeline-and-some-great-places-to-see-it/

The Mitchell Pleiosaur: https://www.oregonpaleolandscenter.com/mitchell-plesiosaurs#:~:text=In%202003%2C%20paleontologists%20discovered%20part,to%2090%20million%20years%20ago.

ROTATIONAL AND ACCRETIONARY EVOLUTION OF THE KLAMATH MOUNTAINS, CALIFORNIA AND OREGON, FROM DEVONIAN TO PRESENT TIME, William P. Irwin and Edward A. Mankinen; https://pubs.usgs.gov/of/1998/0114/pdf/klam_expl.pdf

Geologic history of Siletzia, a large igneous province in the Oregon and Washington Coast Range: Correlation to the geomagnetic polarity time scale and implications for a long-lived Yellowstone hotspot. https://pubs.geoscienceworld.org/gsa/geosphere/article/10/4/692/132166/geologic-history-of-siletzia-a-large-igneous

Types of Volcanoes (A fairly simple, but good explanation of the main types, their formation and the lavas they produce. Interestingly, the North Sister is a mafic volcano and produces low viscosity lavas, with low explosivity eruptions. The Middle and South Sisters, along with Broken Top, are stratovolcanoes producing felsic lavas, which are thicker, more viscous, containing much higher silica levels and gases, which make eruptions more explosive. Newberry in contrast, produces mafic, low viscosity lavas as do most shield type volcanoes. Some stratoes. like Mt. St.Helens have stratified magma chambers beneath, with felsic, magma at higher levels which present explosively during earlier phases, with less explosive, more fluid like later flows.

This was helpful and readable, Volcano Hazards in the Three Sisters Region, Oregon and a little deeper look into this part of the Central Oregon Cascades.

Looking for a little background in igneous rocks and volcanism? This could be helpful: https://opengeology.org/textbook/4-igneous-processes-and-volcanoes/