Science is a pathway to knowledge which shares a particular approach and is careful to eliminate opinion and unsupported speculation, something we are suffering from far too often these days. Science is subject to ‘peer’ review, their work must stand up to scrutiny, criticisms of experimental design, errors in logic. In science you can’t just claim the high ground, you must prove the ‘worthiness’ of your solution. Does it really solve the ‘problem’ you claim it does. (Now if only the world of politics were held to the same standard!) Much of science goes to defining our understanding, proving one theory or another. The demands are strict. Theoretical scientists, on the other hand, are concerned with the ‘holes’ in our explanations. Such science looks into what we don’t know, playing a role when the holes and errors can no longer be ignored. Science is a collaborative method of building, brick by brick, of clarification, followed inevitably by questions, which eventually results in a burst of insight and creativity. Sometimes long held ideas are proven wrong, while the egos of a theory’s progenitors and supporters, dominate their judgement, leading them to cling to them, despite the conflicts, even glaringly obvious errors, delaying the acceptance of the new. It is a continuing cycle of hypothesizing, testing and refining, made more precise, exposing the holes in its own explanation and our understanding, driving the entire process ahead to the next hypothesis and solution. Errors are expected, supplanted with ‘better’, more effective answers.

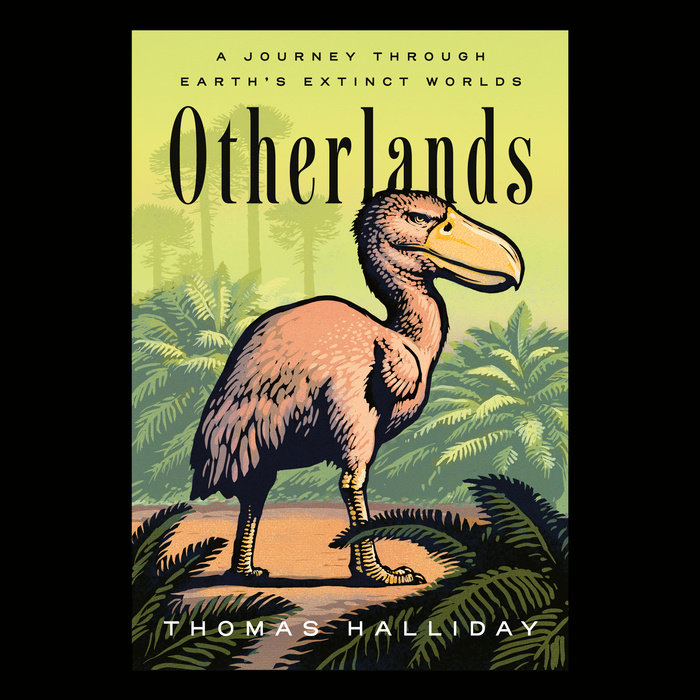

I’ve finished, and had time to think about, paleontologist and evolutionary biologist Thomas Halliday’s latest book, “Otherlands: A Journey Through Earth’s Extinct Worlds”. This is a review, not breaking science. It is a whirlwind trip through Earth’s last 550 million years over which multicellular life began to emerge, evolving to the present day. He does this selectively sampling from different significant periods of time and place. These are of course limited by the availability of fossils and our access to the geological record, problems linked to the condition of that period and place and the capacities of our own evolving technologies to reveal the secrets therein.

Evolution is an intimidating subject. The shear span of time it demands that we consider, is difficult to comprehend given our own puny lifetimes and the brevity of our own species. It has been difficult for me keeping track of the different Eras, Periods and Epochs and the corresponding dates to which they are assigned, as well as the conditions that dominate them, which goes to determining the success and failure/extinction of uncounted thousands of species. But these seemingly arbitrary periods are necessary to make any sense of this at all. Without them, it easily becomes a dismissible mishmash, with Trilobites sharing time with Dinosaurs, tree like Equisetums and giant seed Ferns, alongside Conifers and Sunflowers, primates and ‘lungfish’….Such a framework is necessary as is some familiarity with taxonomy, genetic lineages and the key role of environmental conditions.

Latin binomials and terms for families and clades are themselves another obstacle, that my own familiarity with botanical nomenclature struggle with here. Even Halliday’s limited sampling of species can be intimidating when one is utterly unfamiliar with the groupings, long extinct, he discusses. I wondered if pictures and diagrams would have helped as they do in books like Goulds’s, “The Burgess Shale” which looks at a singular, far more limited, period 500 million years ago. I think it would…but the shear ‘novelty’ of species presented here demands study if one wants to retain such detail. Nevertheless this is a book worth reading…once or twice for the broader understandings it offers.

Geology too is presented, the shifting of tectonic plates, forming and reforming of continents, the changing of oceanic currents and climate. In the case of the Earth, these conditions have varied wildly along with toxically high levels of Oxygen, its near utter absence, carbon dioxide levels far higher then today’s with temperatures and aridity over land masses in which most contemporary organism would perish, to a ‘Snowball earth’ which chased surviving life into the water below the ice. These combine to suggest a dynamic Earth far more changeable than the one we have ‘known’ in our species brief, several 100,000’s of years as a species. But this is a good start.

Lay readers will have to be patient and understand that like learning any topic, this is comparable to learning a new language someone else is using to describe the world you think you already know. To learn it you have to be able to suspend some of what you’ve always taken as given and open your mind to new possibilities…not easy for anyone. It takes a certain commitment. But like learning a musical instrument, or so many other things, once we do, a world of other possibilities open up. It upsets our understanding in a broadening way and prepares us to reconsider long held and limiting ideas. The world we see today is not the world of yesterday, or the day before…nor that of a mere million years ago. Life is truly a dynamic and evolving process and should we choose to dismiss the connections which define the relationships between all organisms of a particular place and time, act as if the world were ‘static’, its conditions constant, along with the life that inhabits it, we are acting in opposition to what we ‘know’ about this world and nature.

Halliday uses his last chapter to discuss this very point. Although he doesn’t use the word ‘hubris’, he is definitely warning us, counseling us to consider these links and the fragility of the entire process of life. When events occur that push the system outside its operable margins, whether catastrophic like an asteroid crashing into Earth, or the accumulative damage imposed by our own species, destroying entire habitats, eliminating whole species or changing the chemical makeup of the atmosphere, their will be consequences that follow. No species survives forever. Extinction’s impacts get lost over time. Extinctions, their stories, in human terms, quickly become fictions that carry little weight when compared to the present, of which our understanding is cursory at best.