I’m a thematic reader, certain topics appeal to me. My tendency is to dive in when they fit into the puzzle that intrigues me, particularly the big one about life; what it means to be alive; what organisms share in terms of their biological function as well as what connects us…all of us, as a species and more broadly across species; the ecology of life, how we fit together, necessarily; how this life would not exist were we truly individuals, separate, isolated, independent organisms and how we delude ourselves when we insist otherwise. One book often leads me to the next. Sometimes several. So I read about quantum physics and how as we integrate that into biology, it transforms that science, adds an element of ‘magic’ to it. Neurobiology. Ecology. Evolution, The embryogenesis of that single egg cell into the the dividing undifferentiated blastula, to a mature organism with its multiplicity of differentiated cells, unique tissues and specialized organs. Metabolism. Gender and sexuality. Perception and consciousness, its complexity and variety. Relationship, function, communication, internal ‘signaling’ and ‘switching’. How concepts of sentience and beauty, language and art, the soul, all spring from the complex act of living…. Integral to it. How species and individuals all play roles, simultaneously in every level of ‘community’ in which they belong/participate, indispensable and irreplaceable, all related parts of an ongoing, evolving, process; one that we are so embedded in that we cannot possibly discern the value of anyone ‘member’s’ contribution, each an element in the larger dance, a ‘process’ which itself, is the point. As Shakespeare once wrote in, “As You Like It”:

I’m a thematic reader, certain topics appeal to me. My tendency is to dive in when they fit into the puzzle that intrigues me, particularly the big one about life; what it means to be alive; what organisms share in terms of their biological function as well as what connects us…all of us, as a species and more broadly across species; the ecology of life, how we fit together, necessarily; how this life would not exist were we truly individuals, separate, isolated, independent organisms and how we delude ourselves when we insist otherwise. One book often leads me to the next. Sometimes several. So I read about quantum physics and how as we integrate that into biology, it transforms that science, adds an element of ‘magic’ to it. Neurobiology. Ecology. Evolution, The embryogenesis of that single egg cell into the the dividing undifferentiated blastula, to a mature organism with its multiplicity of differentiated cells, unique tissues and specialized organs. Metabolism. Gender and sexuality. Perception and consciousness, its complexity and variety. Relationship, function, communication, internal ‘signaling’ and ‘switching’. How concepts of sentience and beauty, language and art, the soul, all spring from the complex act of living…. Integral to it. How species and individuals all play roles, simultaneously in every level of ‘community’ in which they belong/participate, indispensable and irreplaceable, all related parts of an ongoing, evolving, process; one that we are so embedded in that we cannot possibly discern the value of anyone ‘member’s’ contribution, each an element in the larger dance, a ‘process’ which itself, is the point. As Shakespeare once wrote in, “As You Like It”:

All the world’s a stage,

And all the men and women merely players;

They have their exits and their entrances,

And one man in his time plays many parts….

We do not and cannot know the ending. There is none, or rather each ending marks a beginning, any guess that we might offer of an ultimate purpose, of a goal, remains unknowable, beyond the continuing unfolding of life…endless change.. Progress? It’s difficult to say as the earth system collapses and ‘reboots’ over time. The expression of the whole is observable only in moments, in its parts.

The aphorism, ‘it takes a village to raise a child’, begins to get at what it means to be alive, that we all depend on each other, connected, related through the dynamic processes of being, the flow of energy and its ‘in-forming’, the translation of matter and form. We are each a unique expression of this process. If we are ever to fulfill our potential, if we will ever be able to discern what that might be, we must recognize these connections. Our individuality is a selfish story we tell ourselves, one that fires our ambition to differentiate ourselves, to put ourselves ‘above’ others, to claim exceptionalism, and in so doing, lose the larger game playing out before us. As ‘individuals’ we are incomplete, hobbled in our larger social and ecological roles, we devalue ourselves when we fail, individuals rather than the ‘collectives’ that we are. We may act individually, even ‘freely’, but our actions will always be informed by both our past and the actions of all around us. We forever linked across time and space, directly by lines of dependency, recognized or not. We are inevitably part of something much larger than ourselves. We are bonded composites, never truly independent, as both individuals and a species, communities integrated into unique wholes. Even our consciousness is a product of this collective relationship. ‘Shaped’ by and shaping the conditions in which we live. The synapses in our brains, responding and working to shape the world around us and within. We are connected in countless unseen ways, essential and impactful never the less.

Human beings are a confused lot. We do injury to ourselves when we fail to acknowledge our connections, our shared relationships, when we take from, rather than share. We are stronger together, but have learned to doubt that connection, that inter-dependence. Too often we see ourselves as better than, or worry that we might, can’t, be less. Above. We fail to see ourselves as process, existing only in this moment, and the next, in constant states of change. In this fluid state we seek out control, stability, security and forego the fluidity and freedom which is our natural state. We conflate ‘goodness’ with our ‘likeness’, with our own qualities, while we identify others as different, possessing ‘other’ competitive and lesser qualities. Too often threatening. We time and again fail to understand the workings of nature, of Darwin’s profound realization that life is a product of natural selection and mutation, that life, and health, are derived from dynamic, changing processes, that stasis and sameness will lead life down a dead end path to extinction, to a loss of variation, to irrelevance, in which our capacity as a society and species to respond, is reduced, lacking of suitable variants, no longer adequate to meet the demands of changing conditions. Only capable of offering the same ‘solution’ to the ever changing problems we face. When we believe in our own ‘exceptionalism’, when we seize it, and insist on our own individual and species superiority, we fall into traps of our own making, ignoring the necessary connections between all species and whether through the violence of economics, physical force or politics, seize the empty advantage of power and so deny others in all of their forms, weakening and undermining us all. We thus render ourselves as a species more fragile than we need be.

In nature the individual, although collectively essential, is expendable, replaceable. Force cannot change that. It can only lessen our opportunities. DEI, diversity, equity and inclusivity, widely derided today by those clinging tenaciously to individual power, personal liberties, seized at the expense of the ‘other’, is an acknowledgement of the value of all life. Its rejection is borne out of ignorance and fear. In our denial of life we doom our future. Our ‘vision’ thus limited, causes us to look for advantage over, unaware of the injury we do to the whole in the doing and so assure society’s collapse and possibly our biological collapse as well.

One of my most recent reads is mycologist, Patricia Ononiwu Kaishian’s, “Forest Euphoria: The Abounding Queerness of Nature”. It is a critique of how we do science, how we, collectively, look at and live in this world, and in the doing, do damage to ourselves and the world. Her book is a wakeup call, for a return to a science and appreciation for life that we have moved away from. It is in part a paen to the world she knew as a child, once lost, now found her way back to. A world which western science and culture has largely turned its back on. Science lags behind, necessarily, the ‘new’ thinking. It is inherently conservative. Demanding proof. It is often linear and direct. Either/or. Binary. If this then that. But science is reteaching itself now to think in terms of wholes.

The atomistic thinking of the last 300 years has taught us much about the inner workings of life and the universe, of its parts, but not of the ‘miracles’ of wholes, those near ‘magical’ leaps we are beginning to understand through our investigations of the quantum universe, of its roles in life. As a society we are beginning to think more in terms of continuums than in strictly limited binary responses. This is in keeping with the practice of looking at the future, at outcomes, in terms of probabilities. Certainties, when we look into specifics, are less so. What once seemed simple and direct, now is more a product of multiple influences which interact in complex ways. There is very little in the universe that is simply either/or. Our computers may utilize binary logic, but life doesn’t. Very little that exists in the world, outside of the laboratory, is determined by a single variable which can wholly explain a particular behavior or outcome, process or form. The classical physics of Newton, only goes so far. Life is not as simple as one billiard ball striking another. Most phenomena are far more complexly related. Science seeks to explain, to draw ‘lines’ between different events and processes, explain similarities in structure…to a point. But because life and this universe is infinitely interwoven, to explain it in the language of science’s strictly controlled environment of the classic lab experiment, controlling for all other variables, but the one we are testing, so that we can understand its effects, misses much of life. In physics you can read about the 3-body problem, how with three variables it is very difficult to predict an outcome and, over time, with each following event, it very quickly becomes impossible. Quantum physics acknowledges this and speaks in terms of probabilities, not certainties.

Queer Ecology

As we begin to look more closely at other phenomenon from such a limited scientific perspective, in an attempt to understand and predict a given outcome, science is beginning to recognize that attempting to understand a phenomenon solely in terms of its parts, can never explain the whole. Science, as it advances, almost always brings up new questions, while certainty eludes it. Wholeness, being, process, are knowable in only limited ways over brief stretches of time. The very concept of ‘is’-ness, of an object, an organism, existing in time and space, has come into question. The closer we look, the shorter the time frame of our observation, the less ‘real’ that object/organism becomes. We are all process. We take on solidity only over time, a construction, if you will, of our minds we’ve put together, a ‘construction’ wrought over time of memory, the shared story of our existence and our incomplete perception which is always trailing behind.

When, and if we could query individuals of other species, what they see, what they sense and experience, we would discover that their world they understand is very different than our own. Jakob von Uexküll, a German biologist, coined the term ‘umwelt’, that refers the world as understood by each individual given their different perceptions, the capacities and limitations of their perceptions. We fool ourselves when we believe that our idea of the world is the ‘correct’ one, better more accurate than that of any other individual of any other species. As humans, only when we share a common understanding, can our world begin to approach sameness, through a learned process of social universe building. Differences will always be there. What we do with those differences, whether we simply respect them or see them as dangerous, is a choice. But too often we insist that the world must be as ‘we’ see it, that others are wrong. We interpret the appearance, the actions of others, translate their words into our own, adding meaning of our own, some of the other’s value lost, necessarily in the communication. Far too often we reject the possibility of any difference at all…and in so doing blind ourselves to the beauty and diversity of the world. Looking closely enough, we are all different, not better or less than. That difference needs to be reinterpreted so that we remove the valuing that we attach to it and the hierarchical ordering that our culture today assigns to it.

Kaishian takes us down a path that feels oddly queer, but somehow closer to the ‘truth’. No one thing, just as no one individual person, can be truly described, identified, pinned down. Because that person, that idea of them, does not exist. They simply ‘are’. When we observe, interpret and represent them they are our ‘fabrication’ of themselves, abstractions, not the person or thing before us. Who, what, am I, and for that matter, is anyone or anything else? They, it, do not exist in the ‘box’ we might put them in. They are more and different than that.

One of the topics Kaishian discusses is a term I’d never heard of, queer ecology. I have read multiple books and papers on ‘ecology’, the study of relationship between organisms and those places in which they live. But this is new to me and I’m still wrestling with its meaning. Queer, can mean different, unexpected, weird. The action of this kind of classification is self-referential, denoting that this person, organism or phenomenon is outside of what the observer considers ‘normal’ or expected. In a binary world, it is an act of division. It, in the doing, refers to oneself, a comparison, that too often carries a judgement. These days it is often used regarding questions of gender and sexuality.

Queer implies a ‘third’ state, or, more accurately, a range of states between the previously two recognized binary states, male/female, hetero and homosexual. It allows for the possibility of self identification and the rejection of societal norms. It suggests a continuum, a range, a recognition that variation occurs, is natural and carries no value beyond that. No judgement of lesser than. Only different and its alternative opportunities for existence, for richness. It refers to a range of states of being and calls into question those previously accepted norms, standards and states of being. It argues for ‘in between’ and implies a richness of natural responses in any different population, community or system, which is commonly denied. It does not recognize a hierarchy in this. Different is not less than, only different. It greatly increases the complexity of the systems around us. Increases possibilities, richness, options. Whereas insistence on strict binarism, the hetero-normative, is limiting, reductive and places the subjects in a much less adaptive, weaker, position regarding evolution and even survival. ‘Queer’ opens a door between peoples so that they might reach across the intervening space, and it does the same for the perceived gap between species.

The author begins with her own story and returns to it repeatedly through the text. Growing up in the countryside of the Hudson River Valley, in upstate New York, she describes her experiences in the wet squishy underworld, the world behind the world we are taught to value, which most learn to avoid; a world with which she came to feel an affinity, the world of salamanders and snapping turtles, slugs, bugs and snakes, of life in the swamp and culvert pipes draining under the road, the forest, of a world she identified with in its otherness and rightness. She writes of her shared ‘amphibiousness’ with this world, a world in which she found safety and solace as a child, a child who never quite ‘fit’ in. This ignored world, underpinned the recognized world in which she struggled to find her place. Identifying with this amphibiousness, constrained by society’s expectations and standards, of the far more limited, acceptably human world, she longed for a life in which she did not have to deny herself and conform to its expectations. This led to her questioning of convention, of practice, of not only how we do live our lives, but how we do science.

She began asking the question, ‘Who am I?’ ‘Who are we?’ The commonly accepted conceptions of the individual person, of the individual organism, began to dissolve away for her as she examined and studied. Queer ecology causes us to question who and what we and our fellow organisms around us are. Queer ecology??? There is a great deal of variation in gender and sexuality across many if not most species, and Kaishian writes of her ‘discovery’ and examination of many of them that she’s explored in her work In biology. The binary classification of the sexes is very often an error. Her’s is an examination of the animal and fungal world.

[Plants are another step further away from rigid binarism. The majority of species, amongst those that actually form flowers, have ‘perfect’ flowers, each flower possessing the organs of each sex, each capable of producing viable seed. While others are dioecious, with separately sexed flowers. In some cases these separately sexed flowers are on the same individual plant, on others they occur only on separate individuals. Some of these perfect flowers are capable of ‘selfing’, pollinating themselves and producing viable seed. Others require the pollen of other individuals.

Even with perfect flowers there is variation in when the anthers and stigma ‘ripen’, are ‘ready’ to perform. This effects when one flower may fertilize another and when one is ready to receive. Protandry is common in many species. This is when these perfect flowers, mature their stamen before their female stigmas, releasing their pollen before the stigmas have matured and can receive the pollen so pollination is dependent on interlocuters, other pollinating species. In other flowers they may be protogynous, the female stigmas ready before the male anthers.

In other plants, Dandelions for instance, they commonly dispense with the entire plant sex thing, forgoing meiosis in the production of female gametes, instead forming diploid egg cells in the ovary with no need of fertilization and pollination at all, foregoing the process of meiosis, utilizing their intact paired chromosomes in their egg cells to form viable seeds directly, seeds which produce clones of themselves in the process of apomixis.

More than a few plant species possess all of the ‘tools’ for sex, but don’t utilize them in an significant way, trees like the Quaking Aspen, forming huge clonal colonies from their expanding root zone, single individuals which can spread across acres and live for thousands of years.

More ‘primitive’ plants those that evolved their lineages many millions of years earlier, didn’t have flowers at all, yet produced seeds, sans a protective ovary. Even earlier, plants like Ferns and Bryophytes have never produced seeds. They rely on the production of spores, that germinate, growing into an intermediate, different, ‘body’, that then goes through the sexual process of the exchange of chromosomes, which germinate and grow into the mature plant. Gametophytes and Sporophytes, different forms of the same species.

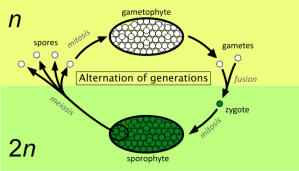

Everytime I think about this I have to refer back to source materials, I just can’t keep it straight in my head and have been this way since my high school biology class. Diagram showing the alternation of generations between a diploid sporophyte (bottom) and a haploid gametophyte (top)

The sporophyte forms from a diploid zygote, the product of the joining of chromosomes from two different individuals. It, when mature, produces and releases the haploid, single chromosome, spores. The gametophyte is a haploid multi-cellular structure which releases single chromosome, haploid, spores. These spores then join forming a diploid, two chromosome, zygote which matures into the sporophyte. It is a continuous two stage process. Each individual goes through these two stages on its way to maturation. These two stages still occur within the more ‘modern’ flowering plants, but the stage is reduced and fully contained, protected, within the plant rather having to suffer the vagaries of the surrounding world.

Then there are the single celled plants, like Algae, that reproduce via simple cell division much like bacteria, often forming up collectively in mats or masses. In these, through the process of mitosis, their chromosomes arrange themselves and each effectively ‘unzip’, then replicate perfectly their other halves forming a ‘new’ cell, a mirror copy of the original. Many ways to be. Many ways to reproduce.

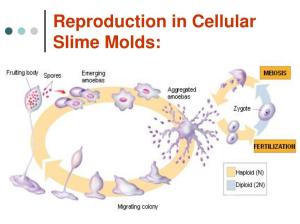

Then there are the slime molds in which in which single celled individuals eventually aggregate and form a spore producing body, transforming their structure, which begins the cycle again. ]

]

Historically science, informed by its own limited world view and prejudices, ignored these less than strictly binary alternatives as ‘abnormal’ occurrences in animal species, and considered them to be anomalies, dismissing them and so missed a huge opportunity to ask questions about the nature of life, relationship, phenomena and behaviors of all types. But these variations are far too frequent to simply dismiss. As with other biases we may carry, we do so in spite of the evidence before us, dismissing it because we ‘want’ to, in order to maintain a ‘world view’. The continued existence of these so called anomalies, along many different lineages, should underscore their viability, even practicality, as species move through time. Such variation is a part of this life. Our prejudices cannot annul them. That’s the ‘problem’ with ‘facts’, when true, denying them takes effort and undermines our understanding of the world and life, demeaning both it and us.

The useless attributes of a species can be lost over time through the process of natural selection. Lineages dying out. In other cases traits may carry on without diminishing in frequency of occurrence when when they pose no disadvantage. They are a link back to earlier conditions. DNA retains a ‘record’ of an organism’s past, much of it lying ‘dormant’ for generations. An organism routinely switches genes off and on as needed. Individuals contain a range of physical traits just as they do many genes that appear to be of little practical use currently. But, over the long term this diversity may be essential for a species survival. Survival depends on diversity. We don’t get to define utility and what does or doesn’t matter. Nature through its complex processes gets to define what is valuable, what is worthwhile. Biology works to conserve diversity as it is essential for survival. It is not ours, the human species, to decide unilaterally, we with our relatively short lives, limited memories and inability to foresee what may or may not be valuable at some future date. Survival is not simply confined to our understanding of a competitive struggle between the strongest. We do not get to determine what constitutes fitness. Proponents of racial purity, of eugenics, can only fail. Virtually every trait any individual organism possesses is a result of natural selection over countless generations, shaping all of those to follow including our capacity for language, to create beauty, problem solve, cooperate, feel joy…virtually everything about us today has been selected from the past because it provided us with competitive options, including our capacity to cooperate, to recognize the value in others, the qualities and capacities they provide the group.

So called ‘cancer’ genes may dispose an individual to a particular cancer…after they mutate, but before that, they provided what is necessary for given essential cellular functions. To eradicate that gene then may compromise the overall health of the individual. We tend to think of these ‘mutations’, essential to the process of natural selection, as mistakes, abominations, weaknesses, but in doing so we fail to realize that that same process is what moves us, any species, genetically ahead. Nothing in life is simple.

To call differences aberrations, is an admission of our ignorance. A denial of the process and patterns that brought life to be. An embracement of ignorance in the face of fact. We deny and exclude them at our own peril. Who are we, with our short sighted perspectives, to do this? When we do, we risk great injury to ourselves and ‘our’ people, in deciding who is valued and who is denied. When we place our biases, our own demands above those of others, other people and other species, we put ourselves at risk, at risk of being wrong. ‘True’ conservatism would tend to support diversity and complexity, not that uniquely human reductive denial of today’s political conservatism, but that which recognizes the health and vitality of the whole over generations, over time.

The Gut Microbiome-Vagus Nerve- Brain Complex

Kianshian doesn’t stop there. She calls into question our very idea of individuality and introduces ideas that illustrate not just our dependence on the ‘other’, but sees us as biological ‘collectives’. Integrated processes which blur the boundaries between us and other, a concept which we ‘conveniently’ reject preferring to define ourselves as disconnected and independent, a state which puts so many of us into conflict as we struggle to define ourselves as simultaneously different and valued, independent, a consequence of which is that we are each very much alone. An inconvenient and adopted ‘fact’ which is demonstrably untrue and critically damaging.

The human brain is popularly thought to be the seat of thought, that singular organ that defines and enables us as superior and independent organisms, capable of not just independent physical movement, which is demonstrably true, but also of independent thought, living in a Newtonian universe of countless independent actors and, as such, captains of our fate, be it good or bad. We live in a world of our ‘unmaking’ in which we’ve dismantled the very direct connections which once joined us, upon which our survival and even mental well being depends. We have never been more ‘independent’, read alone, as we are today, in human history. This is the result of our denial of connection, of relationship, of dependence, which is often attributed as a ‘weakness’, a quality we abhor. We live in a world today which celebrates this brand of independence above all others. We equate it with freedom and in its acceptance have discarded many of the social supports which have long been essential to our survival as a species over our evolution. Strength, fitness, we see as individual qualities. Connection we see as possible threat. Dependence. Immersed in a culture blind to our very essential nature as a species, we have become largely blind to the damage we do to ourselves in accepting this. We put ourselves and society at risk in the doing. We are social animals and are lessened by this break. We cling to the idea of individual strength and accomplishment and fail to understand how we develop as individuals, how we are shaped by our experiences, how our capacity to think, perceive and act in the world around us, are related in direct feedback loops with the social world around us. Our experiences shape our responses, factor into the formation of our synapses, which in turn leads to the operation of our governing endocrine glands, which effect our blood chemistry and our ability to respond to opportunity and threat, how we turn one into the other. The links are endless. Not only are we ‘processes’, we are products of our environment, in its broadest sense, which change over time. Independence is a myth. A fairy tale story. A way for society to affix blame and failure to the individual, when it is the society, broken as it is, as it reserves wealth and power for the few and leaves so many despairing, the world itself in decline and objective pain.

Many neurobiologists, medical doctors and those who study consciousness, perception and thinking, have historically attributed these to the brain. The singular organ and seat of sentience, thought and ‘command’. More and more of those studying consciousness, mind, agency, responsiveness, these days aren’t so sure about this. They are calling into question the possibility of freewill and with it the practice of judgement and punishment. These capacities, they say are less centralized, that the processing and decision making we associate with these operations are more ‘contextual’, that they occur within the entire body, are a ‘property’ of the body and its immediate environment, the space which we occupy, of which we are a functioning part.

This includes the literal billions of bacteria and fungi within and on us, organisms which often permit us to fulfill essential functions within ourselves, in coordination with, ‘us’. ‘Us’, as in ‘I’. While we often speak of the ecological services different species provide for a living community cooling, shading, humidifying, adjusting the pH, increasing the availability of various nutrients, those instances of cooperation within and between species, the same kind of activity occurs continuously inside our bodies in the process of homeostasis, the countless complex interactions that conduct, regulate and buffer our many internal systems, so that we can maintain ourselves in a vital state, within the particular operational margins necessary for health.

Recent work is beginning to define the Gut Microbiome-Vagus Nerve-Brain Complex, a system some are calling the body’s ‘second brain’, that plays a major role in not just homeostasis, but in our moods, physical performance and thinking. These billions of organisms ‘work’ within us to maintain the environment they need within us, playing a role in our internal regulation so that it continues to support them. It is a mutually beneficial relationship and one that determines much of our lives. All of this goes on at a cellular and systems level, directly affecting our lives, on a moment to moment basis and accumulatively across our lives. All of this, this cooperation, is a product of the same natural selection processes that have resulted in our opposable thumbs, our relatively large brains and standing postures, our omnivorous habits, our particular familial and social structures we follow, the variability in our genders and sexuality. To step outside of this and make and impose decisions that run counter to this, is an act of hubris. It has given rise to violent empires, devastating eugenics programs and genocides and the destruction of the landscapes, their living communities and resources that are responsible for the regulation of the earth’s cycling of life and energy. Insisting that we know ‘better’ leads down a path better not taken.

Kaishian notes this. It is important. Our idea of ourselves at almost every level is wrong. We are ‘of’ the environment and it is ‘of’ us…all of us. The boundaries we commonly acknowledge between us, do not exist, except in our minds. Abstractions. Thoughts of selfish and immature individuals. But we can learn.

The Theory of Species Mind

Kiashian posits this concept. I wish she had taken more pages to explain this, but maybe many readers are better versed in this idea than I am. Science recognizes the Theory of Mind (ToM) in humans, our capacity to ‘know’, our personal awareness and a like understanding of this capacity in others, to perceive and function uniquely in the world, so that we can interact in ways that are informed by this understanding. This makes us ‘persons’. Like beings of significance. You are you and I am I. Both have valued and substantial positions that must be reckoned with. Both may possess unique offerings or threats. Western people have not traditionally extended the idea of ToM to other species. They are generally considered to be ‘less than’ us, dumb animals, plants, fungi and bacteria, merely reactive, instinctive at best. Their ‘behaviors’ geneticaly fixed and limited. Without the attributes we commonly assign to ourselves, lacking the ability to ‘consider’, and decide, to alter their behaviors in the face of complex and changing conditions. To attribute any more than this to ‘other’, is considered naive and childish, a weakness. To suggest otherwise is to set oneself up for charges of being sentimental, anthropocentric and ‘unscientific’. Study after study looking into animal behavior, others that consider the possibility for plant behavior, their perceptual capacities, their sensing and signaling which occur within single celled organisms, by which they regulate their internal operation and movements within a particular environment, studies of growth and response in plants to nearby nutrients, water and light and other physical stimuli, to the presence and absence of other organisms around them, are showing that the responses of these so called ‘lesser’ organisms, vary over time, and a range of physical conditions, often dependent upon familial connection, the acknowledgement of others and the services they provide, all of these demonstrating that not only do all organisms sense and respond to their environment, but that they do so individually and collectively with responses that can vary with their unique conditions. They coordinate and share, sacrificing when need be. Sentience, responsiveness is a necessary characteristic of every living thing for its survival and well being. Their response rates vary from ours. They often ‘sense’/perceive stimuli that are beyond our own perceptual capacities. These are issues of survival for them, but they can also be more than that.

As organisms become more complex so do, and must, their capacities to self regulate and interact with their environments, including with individuals of their own and other species. These are adaptive and necessary responses and should be considered tested and learned. If value is to be conferred then it should be done so based on one’s capacities to adapt not reduced to our estimation of their utility to us. Of course this would require a very non-human prescience.

[in the plant/gardening world, plant hunters often search out plants, not just the unique qualities, their aesthetic value and potential utility, but for those possessing capacities for survival under conditions similar to those offered by those sites in which one desires to grow them. As a gardener who for years enthusiastically pursued the garden art of zonal denial, I was always on the lookout for plants that possessed the aesthetic characteristics representative of my theme, but possessed the hardiness that their places of origin conferred upon them. Even in doing this success is not assured. Surprises and disappointments frequently occur. Plants from warmer climes may survive with cold unheard of in their place of origin. While others die succumbing in far milder conditions in which other variables take them down. These may have come from relict populations, pockets of survival that continued on, in spite of the advance and retreat of the Ice Age’s several glacial maximums and minimums. All of this speaks to the dynamism and complexity of life and place.]

Without them genetic lineages perish. The adage that ‘nothing succeeds like success’, is true amongst all organisms, just as is its corollary, that ‘nothing fails like failure’. Attributes, characteristics, traits, are not dropped simply because they have little utility in the short term or in a particular niche locations. Nature operates over the long term. Across generations and geological time. It is inherently conservative retaining these capacities that may not seem strictly necessary. They retain them in their genetics and represent options, elasticity and adaptive capacity. Our concept of utility and efficiency may be important in our economic system, but it isn’t in the biological world, of survival and evolution. The genetic and behavioral banks are strengthened by diversity.

Unnecessary individual and societal ‘behaviors’ may continue, but not if they consistently do damage over time to a species or the supports upon which they depend. The individual may continue down its own ‘learned’ destructive path and so die. It is a feature of the larger population, with its diversity and numbers, to survive. Not the fixed and limited individual. Individuals are always limited. A diverse population contains individuals with varying capacities. The species will survive if it possesses such individuals with the necessary traits to meet the demands of a changing world. Individuals with other capacities, other attributes, may be better suited for the changed conditions and multiply as those incapable of the adaptation do not. Individuals are all limited. We each have limited capacities to adjust within the very real limits of the world. It is the other, the ‘mutant’ to borrow Darwin’s term, the ‘abnormal’, that may contain what the species ‘needs’ to survive and prosper. Their survival shifts the ‘bar’ and the genetics of survival.

Individual and human ‘superiority’ is limited to situations with a set of definable rules. It is a human assignation, it is not a predictor of success in a dynamic world. We don’t get to define what is desirable in any biological sense. In fact our decisions can actively worsen our abilities to survive as we force the world into ever tighter margins, margins and limits with very little room for error. To do this is an act of hubris. There are many stories of this where humans convinced of their superiority charge down that path to their destruction. Wealth and power do not confirm an individual’s superiority. Species collectively utilize their variations to adapt. It is not an intentional process. It is organic and open. Limiting any species’ diversity can quickly lead down a potential dead end. Individuals can only adjust their behaviors within set limits. ‘Successful’ evolution then resides in the species as a whole, and its relationships with others. It occurs in relatively limited ‘steps’. Evolution is gradual.

The Capacity for Play, Practice for Adulthood or Simply Joy

Many ‘higher’, large, multi-celled individuals, participate in activities which can only be understood in terms of play, these are often viewed by science and societies as ‘practice’ for juveniles honing survival skills, or incidental, anomalous, unimportant curiosities. The elaborate mating displays of some species are often simplified, reduced to a contests absent any capacity for joy or appreciation of beauty and creative expression, and the value these capacities may confer on their resulting progeny. But this is our view, our minimal estimation of what they, who we can never truly understand, are. We judge them by our standard and find them wanting. They aren’t like us and so are less than. These human like capacities, we believe, couldn’t possibly exist within ‘inferior’ species. To attribute more to them, is to anthropomorphize them, to grant them human like characteristics, which we can’t do. So, unable to truly understand them, to communicate with them, we reduce them and so often remove them from our consideration as we go about our lives….And, we do this with people as well. With any ‘others’. We force our ideas on them like ill fitting clothes.

Every extant species has demonstrated its collective resilience over countless generations…yet we demean them in this way, but they too are survivors, and most of them have done so for countless generations before we gained the position and power to dismiss them. Individuals of all species will always necessarily die to keep the process vital. How another organism lives cannot be used against them in this way. Individuals all die. Species evolve, adapt or die. The ‘rate’ of regeneration moving in step with ever unfolding change, responding to the changes in their environment and the conditions they present…as long as those ‘steps’ aren’t too great. Too large and extinctions begin to occur. Diversity improves the chances that a species will survive. Five major extinction events have been recognized across time and many are arguing that we are living within the sixth right now, one largely induced by human activity.

Other capacities are more directly linked to survival, but are never-the-less, downplayed, or simply ignored. Because we do not see value, doesn’t mean that there is none there. Value will always vary. We have all evolved different capabilities and different capacities. It is unfair and unwise to judge others.

Others, such as schools of fish and flocks of starlings, often form large groups that move synchronously in mass, in displays which some argue maybe defensive, while others appear to be purely out of a ‘joy’ of movement. How do these lower animals attain such synchrony if they are but ‘dumb’ animals? The author argues that the lack of a large human brain does not preclude such behaviors. Sentience, intelligence, even a certain joie de vivre, may increase social bonding that is advantageous. The flight of birds cannot possibly always be reducible to defensive acts or for the pursuit of a meal alone. Play and exploration cannot be limited to humans. It is very possible that play is an adaptation, a source of joy, that leads to an inner strength, that goes to increasing one’s chances for survival. The capacity to create beauty, to fulfill a need, however we might regard it individually, could serve a similar purpose. Whether or not we as humans assign the same value to an ‘act’, ultimately matters little. There can be purpose in the doing whatever we might think. Such is the characteristic of otherness. Why, we should be asking ourselves has it been so important for us to devalue and dismiss the other?

Kaishian here argues that to not consider these things, puts us, as individuals and a species, at risk with all of the others around us. We humans are powerful and numerous enough today that when we do so, as a group, we put other species and the earth itself at risk. To recognize and value the queer is to remain open to the uniqueness and beauty of the other…all of them. To value only the ‘normal’ is to exclude and deny diversity, and in so doing, weaken the whole and reduce our chances, collectively, of survival. This is both a larger story and a personal one of the author’s own growth, of what we stand to lose in the denial of ourselves, of the pain we will cause all of those different from us. We are all unique. To recognize only what is ‘normal’ in ourselves, is to reduce ourselves to living partial lives. A waste. At the end of our lives we’ll have to reckon with each of our self inflicted injuries as well as those imposed on us by others and those we have forced on to others. ‘Normal’ is too often a destructive fiction and can only cause pain when it is used to limit and control others and ourselves. It is a denial of the fullness of life and its necessity.

Melanie Challenger’s book,“How

“This book is a defense of what it means to be an animal. It doesn’t involve belittling us or losing sight of the obvious differences that mark us out. Nor does it result in a confused preference for what might be thought of as natural. Rather, this is an argument for a deeper understanding of how we think about life. Our animal origin is the story of our place in the world. It’s the basis of how we give meaning to our existence. This is an impossible task without first accepting that humans are animals. This should be straightforward, yet it isn’t. In truth, we live inside a paradox: it’s blindingly obvious that we’re animals and yet some part of us doesn’t believe it. It’s important to try to make some sense of this. And then, once we accept that we’re animals, to think about what flows from that….

What follows is an attempt to make sense of the kind of being that we are….It’s an invitation to refresh in our minds the loveliness of being animal.”

There is much to digest in Challenger’s book and it demands another reading from me and some time to think on its possibilities.

We, these, and other authors write, have made assumptions, sometimes egregious ones, about ourselves that lessen both us and the life of other beings, damaging ourselves and the world around us. We are living smaller, more disconnected lives and are lesser for doing so. These authors argue for uniqueness, weirdness and commonality, for what we all share and the value that our particular uniqueness bestows upon us and so a deserved kindness and respect that is largely absent in the modern, western, world. Differences should be recognized as opportunities and possibilities, not threat.

Kaishian references ecologist and author Robin Wall Kimmerer. They share a common base in biology and ecology, as well as their understanding of ‘family’ and kinship with the members of the living world, a direct connection, relationship. Challenger, the philosopher, may come from a different beginning point, but they are headed in the same direction. Kimmerer writes of respect and gratitude, the ‘gift economy’, the idea and practice of reciprocity and the respect that such relationships call for. Hers is a call to engagement and practice. All three authors sound a call for deeper understanding, not just for the sake of the world around us, but for ourselves.