How Much to Water?

Recommending trees from climates with significantly wetter growing seasons needs to stop if we are to continue growing our population. Landscapes as designed, and managed, are the single largest user of residential water. Recommending trees which ignore this problem is irresponsible. Lower water use residential landscapes are possible. Local codes and recommendations must, however, reflect this priority.

Additionally, how much to water is a bit of a mystery to all of us and especially so to non-gardeners. How much? How often? Our watering practices should be determined by the local precipitation and the tree’s needs. What is commonly done, however, is that we water for our lawns and that largely determines what our trees receive, unless we have separate drip systems. A tree’s root system doesn’t stay neatly between the lines. They quickly extend out well beyond the span of the tree’s leafy canopy. In many cases even 2-3 times as far, taking up water and nutrients. A roots of a tree, planted in a small bed, adjacent to an irrigated lawn area, will move out into the lawn. A tree isolated in a xeric bed with only a few drip emitters, will quickly demand more than such a meager system affords it and such a tree, if it requires summer moisture, will struggle while competing with its nearby ground level growing neighbors. Again ‘neighbors’ should share compatible requirements so all can thrive on the same ‘diet’ and moisture regime.

Remember that lawns are shallowly rooted, generally not much more than 6” deep, so they require water regularly to keep that zone moist enough, so that the lawn doesn’t stress and brown out. Lawns tend to show stress, browning quickly. Our tendency then is to overwater to prevent this, the extra percolating down beyond the lawn’s roots, lost to them, and unseen to us, the lawn remaining green. Don’t apply enough and the lawn stresses, enters drought dormancy, begins to ‘flag’ and quickly turns brown if adequate water doesn’t come soon. It can take weeks to recover its uniform green-ness. We don’t think a lot about it. We just want a lush green landscape. Whatever is planted in the landscape then tends to get roughly the same treatment and this is fine when the need is comparable. When the need of the trees and their underplanting are not, there are problems, which ever one you try to satisfy, stresses the other. Too much water is a waste and/or an agent supporting rot. When we recommend low water/xeric landscapes and then plant trees or other plants with higher water requirements with them, the tendency is to water the entire landscape too much.

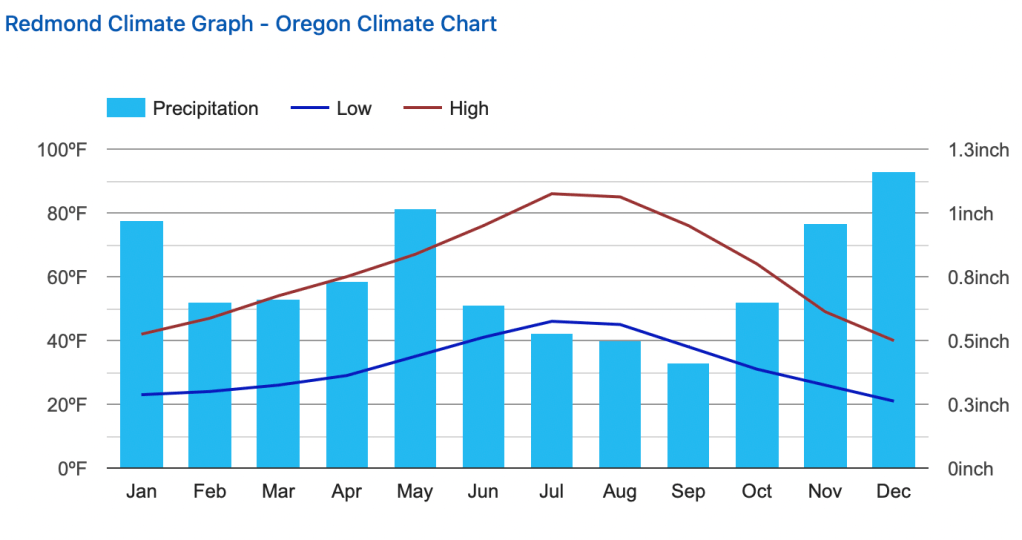

The baseline for irrigation of any landscape is the locale’s precipitation pattern. Those three inches of rain we receive May through September support a far different assortment of plant possibilities than does the 8.6” Denver receives and even more so than the water we deliver to lawns here. Plants use water. A portion is lost to evaporation and some that is over applied, percolates down out of reach. Denver area natives planted here, will require a little more than an inch more per month than we receive, more during drier summers. And that should be applied as showers separated by 1-3 dry weeks to mimic the pattern they evolved with. You can begin to see the problem when including plants from areas with significantly different patterns and totals, Such plantings require more attention and discipline on the part of the gardener. Ideally plants are grouped that share common water requirements. Those that don’t, are grouped elsewhere and watered on their own schedule. Of course if we plant locally appropriate natives our watering is largely reduced to the plants establishment period to get them rooted in and maybe an occasional extra shot when a summer is unusually dry. Everyone needs to keep in mind, however, that keeping a native landscape evenly moist throughout the growing season is not just wasteful, but is often harmful to the natives which are adapted to our summer drought, and can support a population of weeds as well.

Ideally the list of recommended trees, or any plants for that matter, would include rainfall amounts and its seasonal pattern found in their native range, with recommendations of how much additional should be applied locally and when. A list which identifies the needs of plants simply as xeric, minimum, moderate and moist, without more specific after care guidelines, for most people, especially the inexperienced, isn’t enough. How much must be applied to trees in each of these categories? Where are these limited amounts recommended? This is especially true for our human neighbors who’ve moved here from other regions and climates, with little practical gardening experience. What does an additional 2” every 2-3 weeks mean? How is the water being applied? There is needed education.

This is a long term education process. Our old habits and expectations will no longer apply. Ignoring this is what got us into this situation. If we expect to conserve water effectively we must educate ourselves. Again, there is no one size fits all approach that can work. If residents want to be responsible water users then they must learn and adapt. The limitations of the landscape on its own are firm, we are the adaptable species in this scenario…or not. We have been ‘spoiled’ having readily available, ‘cheap’ water available for our use. We’ve been trained to give little thought to irrigation, beyond turning on the system, and turning it ‘up’ if our plants don’t look ‘right’.

There is another complicating factor, soil depth. Many arid land species develop root systems that penetrate deeply down through the soil profile. Those Basin and Range plants that grow in the basins, where eroded soils are extremely deep, can get their roots far below the surface. Locally our soils are often quite shallow. Our local landscape sits on top of a thick layer of Deschutes Formation basalt as is evidenced by all of the drilling, blasting and chipping required to develop land for residential use. In many places basalt lies above the surrounding grade. Soil may fill fractures randomly down to more solid layers. This condition seems even more common in east Redmond where the more recent Newberry basalt flows are visibly above adjacent land. This limits rooting depth and the soil volume available to roots from which to get water and nutrients. This greatly limits what can survive there. Most exotics will require frequent irrigation. These shallow soils, combined with our high summer time evaporative rates, can quickly dry, stressing whatever is growing on them. Trees and large woody shrubs typically require more water than arid and semi-arid grasses and low growing desert adapted herbaceous plants. It’s a major reason why so little grows here without irrigation.

The Western Juniper, Juniperus occidentalis (I posted an article on this tree earlier.)

So we are left with the Western Juniper, a much maligned species. A weed to many, some even wrongly believe it to be a foreign invader, especially those who are ignorant of the local history of development and the region’s ecology. It is attacked as a major source of water loss, capable of consuming and transpiring, massive quantities of water into the atmosphere, in the process robbing it from other plants. Our Western Juniper, is a very well adapted survivor, which under the conditions we have collectively imposed on the landscape, has spread widely and come to dominate some landscapes. There are reasons for this, largely tied to our own collective behavior including grazing and fire suppression. People fail to understand, that ‘all’ of this water our Junipers allegedly suck up, much of it is not necessary for the tree. It is genetically ‘wired’ to survive on far less.

Our Junipers are very effective at finding and taking up what moisture they can find. This is a necessary survival mechanism, without which they would have disappeared in the early years of ‘our’ arrival and disruption. Western Juniper can survive for hundreds of years on thin rocky soils, with absolutely no supplemental water. The water they ‘suck up’ from ditches, canals, ponds, pastures, residential landscapes and golf courses, that water is all put there by us. That water then supports extravagant, relatively rapid and ‘weak’ growth in the Juniper. Their growth is also accelerated under pasture conditions augmented with higher nitrogen levels available to them from the waste of livestock. This response is common amongst many native species when they are provided with more than they need. They will grow unnaturally quickly, in densities they never normally could, at least until those conditions are too abundant for them.

This happens response is promoted amongst the plants we grow in the nursery industry, ‘pushing’ them to size at abnormal rates while also supporting the survival of far more individuals than would ever occur under natural conditions. ‘Nursery’ conditions ‘push’ growth, resulting in ‘bulk’ while often compromising strength and health. In wild nature not every seed can or should grow into a mature tree. The vast majority of seeds simply cannot be supported. Most that germinate, die. ‘Pushed’ as they are in nurseries they tend to be more susceptible to disease and infestation, but nursery growers, aware of these problems, take precautions to avoid losses. They follow various sanitary protocols and consider them acceptable ‘costs’, as production is increased and thus more ‘efficient’. We consider that an advantage in plant nurseries. Many plants are intolerant of those same ‘forced’, or artificial conditions in the nursery and fail, a significant factor in the unavailability of many plants for sale in the trade.

Individuals of any species are, in terms of their health, weakened as the resources they require are either decreased or increased beyond their optimum range. Just as we are weakened by too rich, too available nutrients and other resources, so are plants. Health of any organism is dependent on its needs being met within an optimum range. Too much, or too little, compromises it. Organisms require ‘stress’ and rest periods to maintain strength, health and vigor, each a different quality in every organism. In trees ‘stress’ invokes a conservative response, which in the case of wind increases stem strength, while appropriate soil moisture levels encourage deeper, stronger rooting. There are many others.

That Western Junipers are quick to ‘invade’ areas with deeper soils, where historically, they might follow a cycle, with high ‘recruitment’, germination and establishment, due to supportive conditions and deeper soils, before fire, that burns with relative intensity through the abundant, fuel. Once burned the cycle begins again with the return of native perennial grassland, which will phase into Sagebrush Steppe. Natural landscapes are dynamic, balancing acts of competing communities…and we have, and continue to, upset that dynamic cycling, imposing a narrow, self-serving pattern and function on the wider landscape. Blaming the Western Juniper, is either disingenuous, or simply a product of ignorance. Eliminating it from the landscape is a further denial of nature and comes at a cost to it and us. Planting trees, supplementing, the native landscape, needs to recognize the realities of this place. Continuing to ignore it requires that we invest more and more into maintaining an unhealthy, out of balance landscape system, that is subject to increasing volatility and invasion by other, non-native aggressive growers. This requires that we commit an ever increasing portion of the region’s water to this effort, threatening other needs, while sacrificing opportunities for more coherent, thoughtful, change.

Arid and Semi-Arid Trees of the West Suitable Locally

All of the listed trees below are ‘native’ in the arid and semi-arid West, several to Central Oregon, but not all are to our local desert conditions and so will require some supplemental water to sustain them long term, although in amounts smaller than those required by more commonly recommended and planted trees from many other regions. Included with each tree is the range of precipitation they commonly experience in their own local ranges. That extra amount needed is that remaining after subtracting our local normal, 9”, 8.7” for 2024. While not directly transferable because of soil conditions, these amounts give you a good idea of how much more water will be needed.

How much will they require? Abies concolor, White Fir would have to be supplemented by 11’- 26”, above and beyond our normal rainfall, over the growing season. In general all trees that require any supplemental water, should receive that over the summer months, periodically, not delivered in small daily, or every other day, amounts. Ideally, depending on the tree, delivering it once every 7-14 days, a pattern that would mimic typical summer rainfall areas from where they are found in their native ranges. This allows the water to penetrate more deeply encouraging deeper rooting. More frequent regular surface watering encourages shallow rooting which results in a less drought tolerant plant. Water should be applied slowly enough or on a cycle/soak, irrigate/wait, cycle to minimize runoff and promote penetration. Some trees, it should be noted aren’t tolerant of even this, coming from summer dry areas with deep soils which their root systems can penetrate to depth, where water remains consistently available.

In general, deciduous trees are active summer growers and so require that their totals be applied mostly in the summer when they are actively growing. Evergreens can use winter precipitation over milder periods, some of which are very thrifty water users and can actually be killed by various fungi that can proliferate in evenly moist summer soils. We have a tendency to want to simplify all of this. Doing so can compromise the health of many plants. This is another reason for grouping plants with similar requirements together, trees, shrubs, grasses and forbs, creating viable, supportive communities.

Trees that commonly grow in arid and semi-arid landscapes tend to be widely spaced, don’t provide dense shade and are relatively deeply rooting for their size. These characteristics tend to make them more compatible with arid and semi-arid ground level plant communities. Planting mesic trees, that prefer evenly moist soils during the growing season, creates a direct conflict with such local plant communities. Such mesic trees tend to grow in layered relationships, larger trees overtopping smaller, with shrub layers below and shade tolerant plants at the bottom. Mesic trees then often shade out those lowest ground level plants which are essential definers of desert communities.

Another of the issues with growing exotic trees locally is the shallowness of our soil, generally occurring as a thinly perched layer on top of Deschutes Formation lavas. Many Rocky Mountain and Great Basin trees often grow on far deeper soils and tend to be deeply rooted, not possible in many locations here, and utilize moisture from deeper levels during the summer growing season. Their rooting tends to be deep and not adapted to taking up water shallowly from summer rains. This capacity varies and may include several of the Oaks below….Such trees effectively shut down their roots in higher, drier levels, as moisture levels drop down through the soil profile. For some of these plants, summer showers, remoistening these upper layers, remain inaccessible, because their roots don’t ‘switch’ back on over summer, the water there then either lost to evaporation or taken up by other community members adapted to do so.

Other species, like Pinus edulis and Juniperus osteosperma, however, are very adept at taking up monsoonal moisture from upper soil levels. Pines in general tend to have roots that become increasingly ‘inactive’ as soil temperatures rise with summer’s heating. Assessing which trees will do well then requires local testing under varying conditions. Precipitation totals, the pattern of their occurrence, the presence of winter snow cover, soil depth and type and the application of supplemental water are all important variables.

While I don’t note soil textures below these trees commonly grow in across their native ranges, many do grow in coarse, rocky soils with good to excellent drainage, Others are adapted to fine textured clay soils. While still others don’t seem particularly ‘picky’. Soils with coarser granularity, sandy, gravelly soils, quickly dry out on the surface. This same characteristic protects the soil moisture in deeper levels from evaporative loss which can otherwise be quite high across the arid West with its combination of higher summer temps, low humidity and wind. A dry coarse top layer inhibits water movement up to the surface that will occur in clay soils. A similar effect is gained by applying a rock mulch. Precipitation, or irrigation, quickly penetrates down through it, but protects its loss later, reserving it for the plants themselves. Coarse sand can do the same. (My old fairly high clay content, Latourell Loam soil in Portland, would dry every summer with broad deep cracks as it lost moisture drawing up whatever was available from below in the process.)

Those trees listed below whose normal precipitation range drops to 10” and below can do well here, after establishment, if well placed with little to no supplemental irrigation…they are very few.

Conifers

Abies concolor, White Fir (water (20”- 35”+, mostly as snowpack, a high elevation tree, more with higher temps at lower elevations. May-Oct.).

Calocedrus decurrens, Incense Cedar, zn 4, -30F, (20”+, add 1”+ every 2 wks, May-Oct. Eastern flank of Oregon Cascades)

Cercocarpus ledifolius, Curl Leaf Mountain Mahogany, zn 6, (15”- 24”), Common up in the Ochocos and at elevation in much of the Intermountain West

Hesperocyparis bakeri ssp. bakeri, Modoc Cypress zn 5, (assoc. w/ Pondo Pine) (tolerant of summer water, 14- 30”) most in fall-winter.

Hesperocyparis glabra, Smooth Arizona Cypress zn 6, (10”-25”, 1” per 2wks, Jun-Aug) in the Trans-Pecos in Texas, to southern New Mexico and Arizona in mountains. I have one growing in Redmond.

Hesperocyparis macnabiana, Shasta Cypress zn 6, (12”- 31”), most in fall-winter, thin rocky soil

(Not all Junipers are equally drought adapted. Juniperus communis, and its cultivars, are circumboreal, very cold tolerant, but from regions with moister soils.)

Juniperus communis, zn 2-6, found high in Cascades, Blue and Wallowa Mountains. Circumboreal, the most commonly found conifer in the world. Generally a shrub, but can be a small tree. Grow under well drained mesic conditions.

Juniperus monosperma, Single Seed Juniper, USDA zn7, (10”-15”), in desert grasslands and Pinyon-Juniper woodlands of New Mexico and Arizona

Juniperus occidentalis, Western Juniper, zn 4, 9”-14”, our local native. Unavailable in the local trade.

Juniperus osteosperma, Utah Juniper, zn 5, (9”- 55”) alluvial or rocky sites. Commonly found with Pondo, Sagebrush and Pinyon Pine

Juniperus scopulorum, Rocky Mountain Juniper zn 3, (12”-26”), Varieties of this species are commonly planted locally as hedges. Growing this tightly together puts them in competition with one another for water and nutrients and so will always require supplementation.

Larix occidentalis, Western Larch zn 2, (18”-50”), 28” average precipitation. 6” May-August. Prefers cooler high temps w/ snowpack. (Tamarack)(found w/ Pondo Pine) Common eastern flank of Cascades, Ochocos, Blues and Wallowas. Grown locally.

Picea englemannii, Englemann Spruce, zn 2, an alpine species, 24”+, w/ heavy snow pack and cooler high temps.

Picea pungens, Colorado Blue Spruce, -40F, (18”-24”, 80% delivered during summer).

Pinus aristata, Rocky Mountain Bristlecone Pine, zn 4, (25”, 14” in summer, the remainder falling as snow), a xeric, high elevation, sub-alpine

Pinus contorta ssp. latifolia, Rocky Mountain Lodgepole Pine, (15”- 25”), dominant in the LaPine area, with pumice soils, drier, intermountain forests

Pinus contorta ssp. murrayana, Murray (Sierra) Lodgepole (30” to 60”, mostly from snowpack), at higher elevations, upper montane, 5,000’- 11,000’, sub-alpine, in Cascades.

Pinus edulis, Two Needle Pinyon or Colorado Pinyon Pine, (10” – 27” falling roughly 50-50, winter-summer), hot summers

Pinus flexilis, Limber Pine, zn 4, (15”-50”, over half in summer), In Wallowa Mountains w/ Doug Fir and Rocky Mtn. Juniper

Pinus jefferyii, Jeffery Pine, zn 4, -40F> , (15”-17” mostly winter)

Pinus longeava, Great Basin Bristlecone Pine, zn 4, (3”-12”)

Pinus monophylla, Singleleaf Pinyon Pine, -15ºF, (8”-18” mostly in winter as snow), eastern Sierra Nevada and Great Basin mountains

Pinus ponderosa, Ponderosa Pine, (14”- 30”, significant portion in summer when amounts are in the lower range, more in warmer areas where average temp. Is aove 70F.))

Pinus ponderosa var. washoensis, Washoe Pine, (10”-35”) from harsher, higher sites than the type, lowest precipitation at the highest elevations in SE Oregon, Warner Mtns.

Pinus sabiniana, Foothill or Gray Pine -20ºF, (10”- 70”+ mostly as rain), northern Calif. and California Cascade down through the Sierra Nevada

Pseudotsuga menziesii ssp. Glauca, Rocky Mountain Douglas Fir, zn 4, (25″+) Blue and Wallowa mountains

Oaks and Broadleaved Evergreens

These are all California and/or SW species with a couple exceptions and should all be encouraged as experimental. Several tend more to shrub size than tree. As these are all ‘new’ here their ultimate size is unknown. All are best tried here in relatively sheltered locations. In general Oaks support literally hundreds of other species as providers of both food and habitat. Those in bold face are surer bets, the others worth trying in monitored locations and test plots. All should be grown from seed collected from the more northern reaches of its range as hardiness will generally vary with latitude and elevation.

Chrysolepis chrysophylla, Giant Chinquapin, zn 7, (20″- 130″, the latter mostly as snow in the Cascades), Tree and shrub forms are often considered a result of local growing conditions, higher/drier sites yielding shrubby forms, not strictly genetics. Shrub forms may also be hybrids of C. chrysophyllus and C. sempervirens. Associated with Ponderosa Pine on the drier, eastern flank of the central Oregon Cascades.

Quercus chrysolepis, Canyon Live Oak (zn 3-11), (6”-30”, drier ranges occurring mostly in summer)

Quercus cornelius-mulleri, Mueller’s Scrub Oak, zn 6,

Quercus douglasii, California Blue Oak, (20”-40”, extreme of 10”)

Quercus dumosa,

Quercus durata,

Quercus gambelii, Gambel Oak, zn 3, (12”- 25”)

Quercus garryana, Oregon White Oak, zn 5 (7’- 110”, w/ summertime totals of 1.2” – 25”) lowest east of the Cascades

Quercus grisea, Gray Oak, zn 6b

Quercus hypoleucoides, Mexican Silver Oak, zn 6a, (water deeply every 2-3 weeks)

Quercus john-tuckeri,

Quercus kelloggii, California Black Oak, (zn 7) (12”- 60”+ mostly winter), the most widespread of all California Oaks

Quercus muehlenbergia, Chinquapin Oak (zn 5) (10”- 80” typically 20”-25” during summer)

Quercus oblongifolia

Quercus pauciloba,

Quercus palmeri,

Quercus turbinella, Desert Scrub Oak, zn 6, (16”-25”) summer moist

Quercus x undulata, Waveyleaf Oak

Quercus wislizeni, Interior Live Oak

Deciduous Broadleaved Trees

Acer circinatum, Vine Maple, East Cascades flank to coast, (25”+) snow pack, summer moist.

Acer glabrum, Rocky Mountain Maple, zn 4-8, southern Canada into Mexico, on moist sites, often with snow pack, along edges of coniferous forests, 15”+

Acer grandidentatum, Big Tooth Maple, Rocky Mountains central Montana to Mexico, in canyons, valleys and on stream banks, 1” per week over summer, deeply, prefers deeper soils.

Acer negundo, Box Elder, 18”, often on bottom lands near water, especially in the arid West. Fast growing. Relatively brittle.

Aesculus californica, California Buckeye, some claim zn5b, (13”- 90”, 1”-17” during the summer growing season, higher with higher temps.) Often on alluvial soils.

Amelanchier alnifolia, Western Serviceberry, zn 2, often with Ponderosa Pine, 14”-18”

Amelanchier utahensis, drier, rocky sites, on ridges and slopes, above 5,000’, w/ Big Sagebrush, Washington to Baja, (12”- 20”)

Celtis reticulata, Netleaf Hackberry, Columbia Plateau, widely scattered into Texas and Mexico, often in gallery forests along rivers, such as the John Day Canyon, (18”)

Cercis occidentalis, Western Redbud, zn 6 some say colder, foothills of the northern California mtns., south into S. California, into Grand Canyon, near creeks and canyon bottoms,

Chilopsis linearis, Desert Willow, zn 5-7, deep alluvial soil, (<30”)

X Chitalpa tashkentensis, zn 6

Forestiera pubescens, New Mexican Olive, zn 2-3, (9”- 24”), a shrubby tree/hedge

Fraxinus anomala, Desert AshF, zn 4-9, Colorado to S. California, Texas & Mexico, canyon bottoms to dry hillsides at elevation

Fraxinus velutinus, Velvet Ash, zn 6-8, -10F, (Deep water once every 2 wks.) Desert SW in canyon bottoms and washes.

Ostrya knowltonii, Knowlton’s Hophornbeam, zn 6-8, Mountainous SW woodlands, moist areas, canyon bottoms,

Platanus wrightii, Arizona Sycamore, zn 6a, (subsurface water) riparian, desert SW, alluvial soils, (16”- 24”)

Populus tremuloides, Quaking Aspen, -70F, (15”- 30”) (subsurface water)

Prunus emarginata, Bitter Cherry, zn 5a, -23F, thicket forming, (16”- 32”)

Prunus subcordata, Klamath Plum, zn 5-7, -28F, (17”- 100”), Oregon south Klamath to Lake counties, north through coastal counties

Prunus virginiana var. Demissa, Western Chokecherry, zn 4b, -38F,(16”- 30”) mountain areas

Robinia neomexicana, New Mexican Locust, -23F, (9”- 35”), Can form thickets, Texas to California to Wyoming

Sambucus cerulea, Blue Elderberry, 18”+

Sambucus racemosa var. racemosa, Red Elderberry, 18”+

Shepherd argentea, Silver Buffaloberry, zn 3, -40F,

(13”- 23”), Prairies near streams, California to northern Great Plains

Styrax redivivus, California Snowbell, Calif. endemic, Shasta, Lake, Tehama, Colusa counties and south. One siting in Siskiyou county north of Yreka.

These Yucca are trunk forming in time and can serve as small trees in a desert landscape. I’m currently growing several which should be more widely encouraged. Don’t confuse with commonly available filamentosa varieties.

Yucca brevifolia, Joshua Tree, zn 5b, -13F, (3”- 14” some in summer), Mojave Desert endemic

Yucca faxoniana, Spanish Dagger Tree, zn 5, (10”- 20”) summer showers, West Texas

Yucca elata, Soaptree Yucca, zn 6-7, northern ssp, colder, (avg. 8.3” with 2/3 in summer), Desert SW into S Nevada, Utah and east Texas in Mesquite and grasslands.

Yucca rostrata, Beaked Yucca, zn 5, (some summer water, soak once every two weeks or so.) SW Texas northern Mexico

Yucca torreyi, Torreyi’s Tree Yucca, zn 5, west Texas, New Mexico

A Place to Begin: Conventional Shade Tree Lists for Denver, Salt Lake City and Boise

A separate list should be made for trees recommended as lawn trees for use in Parks with significant turf areas. Turf requires an evenly moist 6” zone at the surface, deeper which would help the trees, is beyond the reach of turf grass roots. This more evenly moist soil layer is more supportive of Mesic, trees that grow in summer moist soils, than those adapted to the arid summer dry conditions of the West. Grass and trees park landscapes here are necessarily compromises. Ideal conditions for one being problematic for the other. This doesn’t include the sun/shade conflict created by trees for healthy lawns both of which tend to require full sun, the trees, however, shading out the turf below.

The Cities of Denver, Salt Lake City and Boise, have good and extensive lists for possible shade trees here, especially where planted in turf or in spaces that will have consistent irrigation over the years. Their lists do include some local natives which should be planted accordingly, but most are more conventional shade trees, that will require supplemental irrigation there, even with their marginally greater rainfall amounts. Denver’s ‘pattern’ of rainfall is also significantly different than the others and it and Salt Lake City both receive higher snow fall than we do which makes a difference. These three would be a good guide for creating a Redmond tree list for typical area irrigated landscapes.

It is also interesting to note that these lists exclude particular trees from use there, including the Pears and Autumn Blaze Maples which are consistently overused locally throughout Central Oregon. They do include others which I would rather avoid here for both aesthetic and maintenance reason, such as the Box Elder, Acer negundo, with its heavy seed load that hangs on and on. Other trees present structural problems for me, but that should be addressed on a case by case basis. Overall, municipal tree lists should be as diverse as possible to avoid future disease and infestation problems. Limited genetics translates into higher disease susceptibility. When a disease or problematic insect does appear locally high populations with limited genetics can be supportive of quick ‘penetration’ and rapid decline of the urban forests. Whereas with diverse plantings in terms of species and their genetics, such problems may never get started as the pool of vulnerable hosts will be smaller. Of course this works against those who like the aesthetic of uniformity in their street landscape. Uniformity and health are often thus in opposition to one another. A large and varied list then is desirable at both the broader City wide scale and at the smaller, with diverse plantings even within particular limited developments. By diverse I do not mean random. All such plants should be well suited for the given conditions and maintenance practices, which as discussed above, is a problem when one’s locale presents arid, desert conditions, generally incompatible with the vast majority of even temperate tree species.

An issue not addressed in any of these lists, nor in Redmond’s current list, is the fact that the trees species and the spacing or stand density of those trees planted should be compatible with the underlying landscape. This is an issue here for those attempting to grow xeric landscapes with local and regionally appropriate native plants as these tend to be plants that require full to nearly full sun and grow in landscapes which, if they contain trees, do so only when they are widely spaced. Arid and desert landscapes would never support a closed canopy grouping of trees. Such conditions would lead to the rapid decline of the understory. I noted this condition when I reviewed the landscape plan for the Redmond Area Park and Recreations District’s new pool/community center, in which designers made an honest attempt to create an appropriate, xeric, understory/ground level planting, while the City’s code seems to require too tightly planted trees overhead and, simultaneously a tree planting that requires far more water than the xeric landscape below. This conflict is built into the current code as written and applied and needs to be amended.

Lastly, and a point I made above, the list should be suggestive, not proscriptive. If the City wants a healthy urban forest then code needs to allow the use of arid, western native trees which are not widely grown or offered by the nursery trade today. Because ‘we’ haven’t been doing this, this will require some experimentation, which means that there will be failures. Because of the nursery industries ‘habits’ the caliper/size rule also needs to be relaxed. This will allow them to experiment with other trees in smaller numbers without such a risk of devastating loss. When property owners/developers apply for permits trees that at maturity are expected to stay within size limits and meet whatever water/irrigation requirements we might have, they should be allowed. This will require that the staff doing the review understand the tree and the growing conditions, but this is necessary to have an appropriate, thrifty and healthy urban ‘forest’. Tree spacing requirements also need to be relaxed in general for the majority of development situations because of the conflict between tight, regular shade tree plantings and the sun needs of a healthy locally xeric, native planting. All of this will require staff and public education and outreach with those growers willing to grow locally appropriate tree stock. To ignore all of this, to continue with past practice, is to continue adding to the problem.

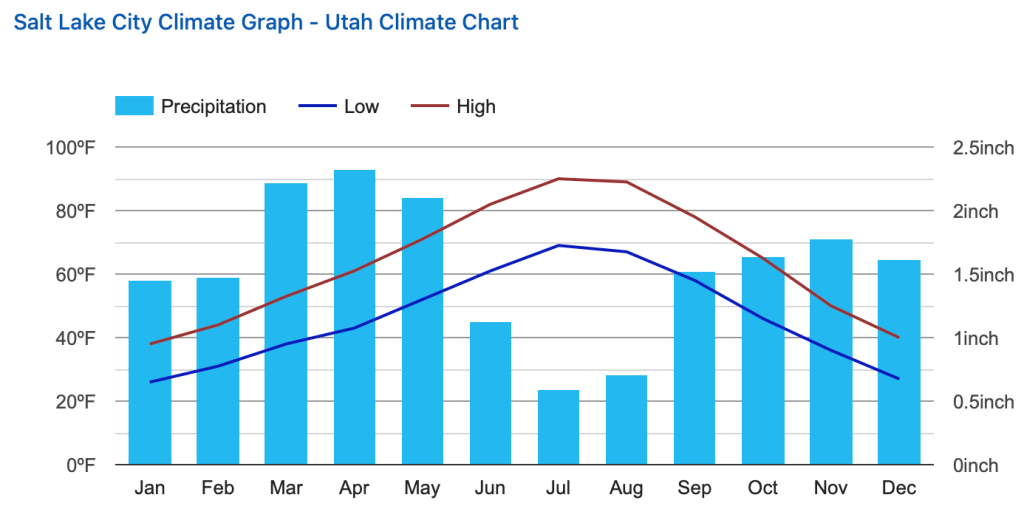

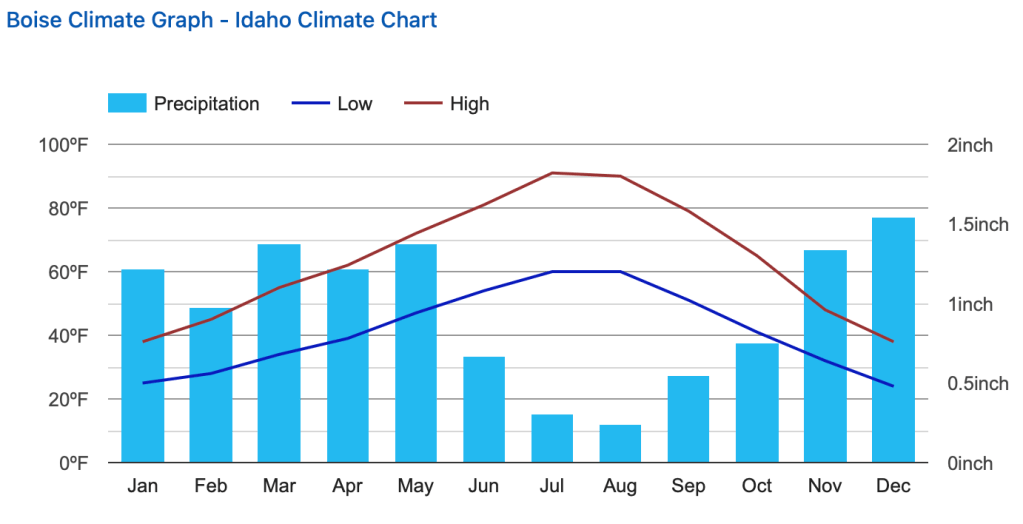

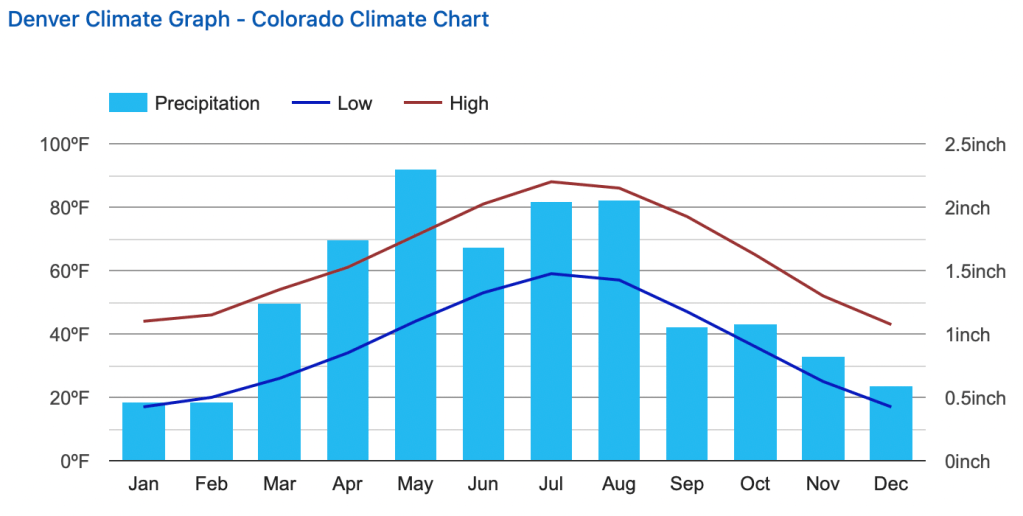

I include the following four charts for their climate comparisons between Redmond, Boise, Denver and Salt Lake City. While there are many similarities, the differences, particularly in rainfall, are notable. Salt Lake City receives 19.5” of rainfall annually, with dry summers comparable to ours, and 53” of snow. Boise has an annual rainfall of 13”, again with dry summers and 17” of snow. Denver receives 16.7” of rain annually, with significant summer rainfall and 60” of snow, a significantly different precipitation pattern than ours.

A Concluding Question

What are we doing here? What is the purpose of this list of trees and various policies, ordinances and rules that accompany it? When we speak of the ‘urban forest’ we need to step back for a second and remember that this piece of the Intermountain West is a desert, that the idea of a forest existing here is wrong for all of the climate and soil reasons I’ve discussed above. The only ‘forest’ that can exist here with our particular conditions, without a great deal of added resource, water intensive, intervention, is the Juniper forest/woodlands which are, as I’ve discussed also, problematic here. They are extremely flammable. The alternative forest that everyone seems to want to create here is a water intensive landscape foreign to a desert, a green coniferous forests of the mountain West or the mixed and deciduous forests of eastern North America and Europe. These are all in conflict with the conditions here. It isn’t that far off or as ridiculous as the idea of creating a new Disneyland north of the Arctic Circle. Sure we could do it, but at what cost? We HAVE been doing it.

The idea of large leaved deciduous forest in the desert here is absurd, the fantasy of a people disconnected from place, that rather than adapt themselves, and their expectations, to the realities of a place, insist that because they can do it, they do so. Redmond is not an oasis in the desert, a way station offering rest for weary travelers. It is a city of thousands, a destination, an extravagance, an enticement, a town sustained by its growth. Another Anywhere, USA, being marketed and sold. Consuming the land, extracting what profit is here, leaving a legacy of what, behind? Can these things be done? Of course they can. We do the ‘impossible’ all of the time. They are triumphs of will. Even Heroic stories of overcoming immeasurable odds. A reordering of life. But what is gained from this other than a statement of potency. Whoopee! What a little thing to gain at such a price…a cost which we’ve never really taken the time to understand. We move here because of the beauty and opportunities posed by this place, bought into a familiar package, the home on a familiar landscaped street and that consumed what was here before. Turned it into any other place. ‘Develop’, as if we were transforming it into a fuller, richer, more mature expression of itself, while converting it into something entirely different than it was, less than, a familiar pattern, an ill fitting copy of what we’ve done before. Without doing any kind of serious cost/benefit analysis. What is lost, simply goes undocumented, unremembered. The loss felt viscerally, by some, but never truly accounted for before we just move on to the next desirable place and begin again. Landscape like any other consumer item, desired, consumed and expelled. Used up.

Or we could do it right. Create a place in response to what is central to it. Something of utility, sure because it must be, but also something beautiful, vital and healthy, capable of living WITH that which lives and endures here, not a place consumed, stripped of its inherent value and planted with trees of transitory value, ‘fragile’ extravagances, but something enduring, appreciated and, in return, supportive of that within ourselves, something of this place. This is all about making the effort, the ‘bother’, to understand first, where we live, what it requires and what it gives, before we irrevocably change it.

Boise/Treasure Valley Selection Guide. https://www.cityofboise.org/media/4078/tree-selection-guide_second-edition.pdf

Salt Lake City tree list https://www.slc.gov/parks/urban-forestry/urban-forestry-suggested-trees/

A list of native trees in Utah. https://www.slc.gov/parks/urban-forestry/urban-forestry-utah-native-trees/

I also found the following helpful:

SELECTED NATIVE TREES OF NORTHERN NEVADA Are They Right for the Home Landscape? JoAnne Skelly, University of Nevada Cooperative Extension, Special Publication, 06-04

Yeah Lance! Keep up the good work!!

LikeLike