Those who follow such things know that I’ve been involved in the preservation and enhancement of Redmond’s Dry Canyon, joining with others to form the Friends of North Dry Canyon Natural Area as an advocacy group, working to educate the public about its qualities and fragility, while also providing ‘boots on the ground’ with clean up projects and the control of threatening Invasive plants. Most recently we’ve been supporting other groups and participating with a guided naturalist walk, a bat walk and a recent Botany and Birds, walk with the High Desert Chapter of the Oregon Native Plant Society and Queer as Flock, a bird watcher’s group. We’ve been advocating for better signage, a trails management plan and for increased efforts to control the illegal use of electric and gas powered motorcycles in the Canyon. Additionally we have be doing the Juniper survey work for the City, to help create a plant data base linked with the City’s GIS program to aid them/us in the development of an effective management plan for Dry Canyon. We’ve only been recently notified, along with the rest of the public, that the City has a new Dry Canyon Firewise Management Plan (a PDF is linked below), which we were assured included participation by foresters, local natural resource and conservation groups…yet, somehow, they’ve produced a one dimensional plan with the singular priority of eliminating the chances of a catastrophic fire, while ignoring virtually all other priorities!!!! Continue reading

Category Archives: Parks

On Our Western Juniper Survey in Redmond’s Dry Canyon

This is an explanation of the importance of the survey work being done by the Friends of North Dry Canyon Natural Area, FNDCNA, and it’s role in the creation of a broader management plan, and a fire management plan, that addresses both community safety needs, as well as those of the Western Juniper and Sagebrush steppe plant communities in Dry Canyon. This is a 160 acre portion of the Canyon Park that stretches 3.7 miles, north to south, through the City, a remnant of one of the canyons formed by one of the previous courses of the paleo-Deschutes River, (There were at least two, one some distance east of Redmond’s location, joining with the Crooked River at present day Smith Rock State Park. The current Deschutes River flows 4 miles to the west of this location through a canyon carved in its earlier stages by Tumalo Creek.) Continue reading

Holodiscus microphyllus, Rock Spiarea in Dry Canyon

Another less common slope dweller is Holodiscus microphyllus, or Bush Ocean Spray, a deceiving name, or Rock Spiarea, which is also somewhat confusing. Confusing because Spiarea is the genus name for an entirely different genera of shrubs. So I call it simply Holodiscus. ( Botanical names can be confounding to the uninitiated. I’m not a big user of mnemonics, but I still remember first learning this plant’s close relative, Holodiscus bicolor, and the phrase immediately came to mind, ‘Holy Discus, Batman!” I know, silly, but I doubt I will ever forget that plant.)

- The three darker shrubs, here are Holodiscus. There’s a Wax Current at the bottom of the pic still in flower just above it in light gray is some gray rabbit brush. more of each or scattered up slope. The tumbled boulders are part of the fragmenting canyon rim, originally deposited as a part of the Deschutes Formation around 5 million years ago, about 4.5 million years before the Deschutes River was redirected to its course here where it carved the canyon over a period of around 300,000 years.

- The leaves are very small and relatively thick, both of these traits are common among plants native to arid country, while many desert plants also retain their leaves, conserving nutrients and water. Like all deciduous plants Holodiscus must spend a lot of energy, and material reproducing leaves, before they can begin photosynthesis and replenish their starch/energy stores. Evergreens/evergrays are always ready to grow and take advantage of moisture and unseasonably warm temperatures at any time of the year.

- The Oregon Flora project has been compiling a descriptive list of all of the native plants in Oregon. Each red dot represents where a sample was collected from by botanists. Many of these samples are preserved in herbaria for research purposes. As with all such maps, these dots don’t mean that the plant will not be found someplace else. Botanists have not examined every square inch of the state.

- This will all pop open as little 5 petalled, ‘rose’, flowers.

- Holodiscus on the eastside slope early July, their buds expanding.

This typically occurs on the eastern flank of the Cascades and in the mountains of SE Oregon. The common name, ‘rock’, suggests its preferred sites. I’ve not seen one in Dry Canyon bottomland. It seems most common below the east rim north of the Maple Bridge. Continue reading

That Gray Stuff? It’s All Sagebrush…Nope

Part of the Dry Canyon plant series

Everybody knows Juniper and I suspect that a lot of people who think they know Sagebrush, that ubiquitous gray shrub you see everywhere, may be confusing it with other plants, blurring all ‘gray’ shrubs into one. Now this may not seem to be a big deal, but if you are trying to manage a landscape with these in them or trying to create a landscape which reflects the local plant communities, then it becomes much more important that you know what you have so that you can evaluate your landscape’s condition and decide upon what you may need to do, or stop doing, to meet your goals. Continue reading

The Cut Leaf Thelypody in Dry Canyon

[Plants of the Dry Canyon Natural Area – This will be the start of a new series focused on the plants of Redmond’s Dry Canyon. I’m creating them to be posted for ‘local’ consumption on the Friends of North Dry Canyon Natural Area. It’s a City Park including about 166 acres at the north end of Dry Canyon Park which the City has identified as a Natural Preserve. The group works as an advocate with the City, on public education and helping with on the ground work projects. I’ll identify each such post here.]

- This years new growth emerging with last year’s inflorescence dried and nearby

- Flowering in early stages. Later the terminal continues to extend and the seed pods develop below.

- An inflorescence displaying its almost ‘orchid’ like flowers

- A map showing locations from which formal collections were taken as part of the Oregon Flora project

Mowing Firebreaks Across the Dry Canyon Bottom, Good Idea or No?

Mowing weakens the native plant community and aids the growth of weeds.

Mown adjacent to unmown. Aggressive spreaders will fill in more quickly and because of the weeds already in place, they will sieze a larger proportion of the mown area as they grow and spread.

While recently walking home through the Canyon, last month in December, I noted 8 new strips, presumably ‘fire breaks’, mown across relatively flat and uniform sections of bottomland, each maybe 50’+ wide, spanning the bottom between the paved eastern path and the the main dirt western bike path. While I understand the thinking here, removing ground level fuels, this is a single purpose treatment that works counter to the Park’s purpose as a natural area preserve. Mowing down the Rabbitbrush, a ruderal, transition species of the Sagebrush Steppe plant community, delays the development of a healthy native plant community and encourages an increased array and density of weeds and invasives. Mowing this way provides open space for weed species already in Dry Canyon, as well as those not yet here, giving them larger ‘launch points’ from which they can spread into the rest of the Canyon. Mowing weakens natives, which are naturally slower to rebound from the damage than the aggressive weed species. Continue reading

From 0’ – 3,000’ in 70 Million Years: Building Oregon, Dry Canyon, The Shaping of Redmond and the Geology of the Paleo-Deschutes, Part 3

Cascade Volcanic Arc –

Over the last 2.5 million years, roughly corresponding with the Pleistocene Ice Age, there have been at least 1,054 volcanoes in a ‘belt’ from Mt. Hood running 210 miles south to the California border and then, after a break, continuing to Mt. Shasta and Mt. Lassen, in a band 16 to 31 miles in width. These latter two, southern most of the Cascades, show no effect of glaciation from Glacial Periods. They were far enough south of the Glacial Ice to be unaffected. The material ejected and flowing from these many volcanoes and vents come from the crustal material of the subducting Juan de Fuca plate. The Cascades are a defining feature of our region in terms of aesthetics, but also as a shaper of climate, as well as being a physical barrier limiting the movement of organisms and thus goes to determining the ‘shape’ of our lives here. The Arc is still active, magma is still being ‘delivered’, building incredible pressure below through these same processes which have shaped this place to date. While we may assess its various mountains as ‘active’ or not, the volcanic arc, is still very much a factor in determining our long term future. Where it will next erupt from, and what form that will take, is impossible to say within any degree of confidence. But the earth’s tectonic plates are still in movement. Magama is still slowly, but inexorably, coursing through its crustal layers and the movement and pressures will continue to result in further eruptions. Continue reading

Over the last 2.5 million years, roughly corresponding with the Pleistocene Ice Age, there have been at least 1,054 volcanoes in a ‘belt’ from Mt. Hood running 210 miles south to the California border and then, after a break, continuing to Mt. Shasta and Mt. Lassen, in a band 16 to 31 miles in width. These latter two, southern most of the Cascades, show no effect of glaciation from Glacial Periods. They were far enough south of the Glacial Ice to be unaffected. The material ejected and flowing from these many volcanoes and vents come from the crustal material of the subducting Juan de Fuca plate. The Cascades are a defining feature of our region in terms of aesthetics, but also as a shaper of climate, as well as being a physical barrier limiting the movement of organisms and thus goes to determining the ‘shape’ of our lives here. The Arc is still active, magma is still being ‘delivered’, building incredible pressure below through these same processes which have shaped this place to date. While we may assess its various mountains as ‘active’ or not, the volcanic arc, is still very much a factor in determining our long term future. Where it will next erupt from, and what form that will take, is impossible to say within any degree of confidence. But the earth’s tectonic plates are still in movement. Magama is still slowly, but inexorably, coursing through its crustal layers and the movement and pressures will continue to result in further eruptions. Continue reading

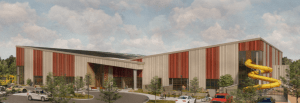

Redmond’s New Community Center/Pool and the Anti-Government Bias: This is What Community Failure Looks Like

This is the rendering of the new facility’s south entry. It’s the banner on the RAPRD’s announcement of Novembers funding levy for the new facility.

Much of what I write of and post here are topics concerning ‘place’, its centrality to life, including our own. This post is specific and narrow, focusing on a non-gardening, non-horticulture, activity important in my life, swimming. I am recently turned 70 years old and their are many physical things I can no longer do and others I have had to modify, given my record of injuries and ‘weaknesses’ of my body particular to it. I have always ben physically active, craved movement and enjoyed the sensations of moving through ‘space’, of strength and competence, of engagement with….I would run, climb over things in my path, do things to prove that I could, explore the world in front of me; physically, and test that understanding. I enjoyed, and still do, the feeling of being ‘capable’. It is a necessity for me, just as is my mental engagement. It is of the same piece. As I age now, while my physical capacities have lessened, sometimes because of my past efforts, I, like a machine, have been wearing out. But, unlike machines, that physical activity, that stressing and testing of ourselves, allows us to stay capable and strong, a response within limits, to the stressing we subject ourselves to, as long as we get enough rest, have a healthful diet and recognize our own limits.’

I haven’t been able to run or participate in sports that require it, without significant consequence, for quite a few years now. The recognition of my own limits, lead me first to yoga, which I practiced regularly and incorporated into the physical movement of my daily work during my working years. While not ‘slavish’ to my practice, I still do this adding in some specifically core strengthening exercises. When, almost thirty years ago, a local public pool was significantly renovated, I began to lap swim, to help with my upper body and core strength as well as my flexibility. The demands of my work were such that if I didn’t do something, the physical demands of my work, which were greatly lessened during the continuous running around of summer, lead to a weakening of my upper body, just as I would be back to placing it under most demand. As I was aging my spinal anomaly was becoming an ever bigger limitation and I was looking about for solutions. I wanted to be able to continue my work in horticulture/parks and was afraid my career might end with me in chronic pain and incapable of doing the things that gave my life purpose and direction. I overcame the idea of boredom and tediousness of swimming face down in a pool lap after lap, as well as my unease with breathing while face down in water, and both my health and sense of well being improved. I still swim. It has become essential. I know what stopping for a significant amount of time means for me. So when we moved, having ready access to a pool was a top priority for me. We bought a home in a community with a lot on which I could garden, with a view of the Cascades and a pool…at least the promise of one. The pool has not yet been built. Continue reading

The Much Maligned Western Juniper: The Role of Juniperus occidentalis in Central Oregon

Old growth Junipers near Cline Buttes. These two rooted down long ago on top of this lava flow. Much of the lavas here were produced during the Deschutes Formation over many thousands of years more than 5 million years ago. Surface lavas, cliffs and slopes define the area with a few sediment filled basins dominated by Sagebrush and Bitterbrush.

The Western Juniper is the singular native tree of Dry Canyon and the immediate Redmond area. I grew up with it here in Central Oregon. When we moved here in ’61 i remember driving north after passing through miles and miles of various Pine forests, which eventually yielded, riding in our VW bus, as we left Bend. Bend sits within the ecotone, the relatively narrow transition zone, between Ponderosa Pine forest and Juniper steppe. What were these trees? Coming from California’s Salinas Valley, the landscape could hardly be more different to a six year old. So different in form and detail, Junipers squatted darkly across the landscape, nothing like the tall, majestic Pines or Oaks I was more familiar with or even the Lodgepole Pine we drove through across the pumice plain of the LaPine area. Continue reading

Weeds, Weeding and the Health of Our Public and Private Landscapes: an example from the ‘hood

Every gardener is a weeder. Gardens are created landscapes, often expressions of the individual gardener or, lacking of intent and design sense, those of a chosen designer. We live in our landscapes as active, responsible, creators, participants and stewards. Gardeners are trying to create a particular look or to grow particular plants native to their area, or with ornamental value or food plants to feed themselves and their families. Some of us are simply pursuing what we understand to be a healthy relationship with one’s place, to undo the damage and allow a new healthy and vital landscape to grow. These are landscapes of our choice. Our intention and control results in various volunteers and weeds finding their own place and so follows the need for weeding.

We watch carefully, monitor the impacts of our work, attempt to understand what result is moving us closer to our goal and which might be indicators of further loss. Landscapes and gardens are incredibly complex systems and anyone who claims to have all of the answers is fooling himself and you. Our landscapes are broken, by us and our predecessors. The Pandora’s Box of weeds and disruption was burst open long ago. The only way ahead is to find a new path. Weeds are here filling the niches we have collectively made and maintain for them. The more one is surrounded by aggressive, well adapted weeds, the more time we must spend controlling them. While this can be significant, gardeners mostly take the work in stride, a necessity to reach our goal, a goal which may be the simple act itself, of working in concert with our place…open to its teachings. Gardening, is a way of life, a smaller scale version of farming and the management of large ‘natural areas’ with their attendant commitment, rhythms and demands. Continue reading