Agave colorata before flowering initiation, growing nearly horizontal, with a broadly cupped lower leaf holding water. From the Irish’s book, “Agaves, Yuccas and Related Plants”, “The leaves are 5-7″ wide and 10″-23” long [mine were all at the small end of this range] They are ovate ending in a sharp tip….The leaves are a glaucous blue-gray and quite rough to the touch. The margin is fanciful with strong undulations and large prominent teats of various sizes and shapes. A very strong bud imprint marks the leaves, which usually are crossbanded, often with a pink cast [not mine], and end in a brown spine 1-2 in. long.

This is one of the first Agaves I ever grew. Pictures on line of its rosette first caught my

interest, their leaf color, substance and sculptural qualities, the margins of its broad, thick leaves, with their rhythmic rounded ripples, each tipped with a prominent ‘teat’ and spine. This is not a large plant, typically growing 23″- 47″ in diameter and my plan was always to keep it in a pot as it is from coastal areas of the Mexican state of Sonora, found sporadically in a narrow ‘band’ south into Sinaloa.

Agave colorata is very rare and uncommon in nature and growing on steep slopes of the volcanic mountains in the coastal region in Sinaloan thornscrub. It often emerges from apparently solid rock cliffs sometimes clinging high above the water below.

Growing in Sonora and at Home

It is poorly adapted to our wet winter conditions though it is reputedly hardy into USDA zn 8, or as low as 10ºF. Its natural northern limit is thought not due to cold, but by excessive aridity in the northern parts of Sonora. I didn’t test it, leaving it outside under the porch roof, bringing it in when forecasts called for below 20ºF, as any plant is more susceptible to cold with its root zone subject to freezing. With perfect drainage and overhead protection, you might be able to get away with this in the ground, but the combination of significant wet with our cold is likely too much…still if someone wanted to try….At best I suspect this one would still suffer from fungal leaf diseases, disfiguring the foliage.

This is usually solitary, but it can be found occasionally in small clumps/colonies up to nearly 10′ across, pushing up against each other on their slowly growing and short ‘trunks’ to 4′ high. My plant produced just a few pups over the first third of its life.

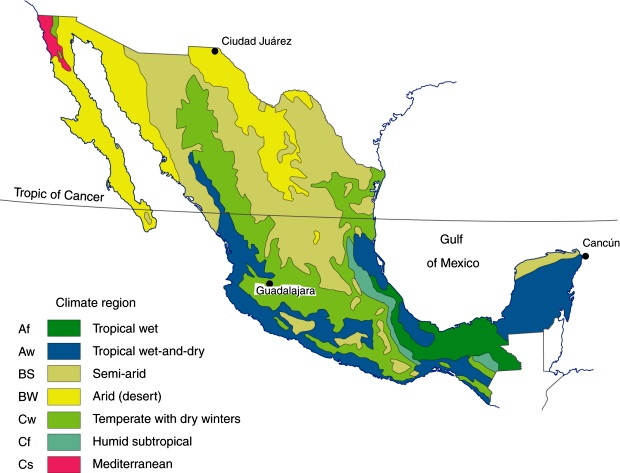

I wanted to include a climate map of Mexico. This one utilizes the classic Koppen system designating the various climates based on temperature and precipitation and their seasonal patterns. Here it has been modified by Mexican climatologists to better reflect Mexico’s complicated geography…even so, because of the abrupt changes in elevation, and land forms, different climatic conditions can occur in close proximity to one another. Mountains can create wetter and drier areas that on a map of this scale are lost.

Sonora has three distinct geographic areas all running along a ‘line’ from the northwest toward the southeast, the Gulf of California and its associated coastal landscape paralleling the Sierra Madre Occidental, sandwiching plains and rolling hills in the middle. The coast and plains/rolling hills are arid to semi-arid, desert and grasslands, while only the higher elevation of the easterly mountains receive enough rain to support more diverse and woody plant communities, scrub and Pine-Oak forests.

This map comes from the Arizona Sonoran Desert Museum. The link takes you to one of their pages which discusses the natural history of the desert, thornscrub and tropical deciduous forest of Sonora.

This region also varies north to south, the climate drying as you go north into the Sonoran Desert. Moving south on down into Sinaloa, and further, is the some what wetter ‘dry deciduous forest’ biome with an array of woody leugumes, including several Acacia. Agave colorata resides in the transition zone in between, in the portion of ‘thornscrub’ near the Sonoran/Sinaloan border. North and south the Thornscrub itself changes in composition. The Sinaloan Thornscrub serves as a transition zone between the desert and the slightly wetter, taller growing, Tropical Deciduous Forest that continues the south. All along this band running north on into Arizona’s Sonoran Desert are various columnar cactus a food source for Mexico’s migrating nectarivorous bat species. It is a unique flora community, containing species from bordering floral regions and other species unique or endemic to this transition zone itself. The area continues to be under threat, primarily by cattle ranching that moved into the region in the ’70’s and ’90’s bringing with it clearing and the introduction of non-native and invasive Bufflegrass, Pennisetum ciliare, also known under its syn. Cenchrus ciliaris, for pasture. Bufflegrass is also a serious problem north into Arizona. In Sonora many of the cleared woody species have since begun moving back in, while the smaller, more sensitive species have not. Climate change promises to further squeeze it. (The World Wildlife Fund maintains a website with good descriptions of many eco-regions I sometimes find it very helpful when trying to understand the conditions of a plant I’m less familiar with.)

When growing plants like this, one should keep in mind the concept of heat zones. The American Horticultural Society has created a map of the US delineating its ‘heat zones’. It is based on the average number of days an area experiences temperatures over 86ºF. At that temperature most plants begin to shut down their metabolic processes…they slow their growth. Check out the AHS map (AHS US Heat Zones pdf.) and keep in mind that we are warming up! The AHS map has us, Portland, OR, in zone 4, meaning we experience 14-30 days with highs over 86ºF each year. Last summer, ’18, we actually had a record 31 days over 90ºF! Now consider that the coastal/plains region of Sonora likely experiences between 180-210 such days! Agave colorata may not need this, but it is certainly adapted to such a level of heat stress. Something to think about, especially when you consider that we receive the bulk of our rain over the winter when our daily highs and lows average for Nov. 40º-53º, Dec. 35º-46º, Jan. 36º-47º, Feb. 36º-51º and Mar. 40º-57º…keeping in mind that we could freeze on most any of those dates. The Sonoran Desert receives its minimal rainfall in a summer/monsoonal pattern….This is why bringing such ‘low desert’ plants to the Pacific Northwest can add another degree or two of difficulty to your success!

Aug. 26, 2018 I could have taken a similar picture anytime over the last several years. The stem is completely prostrate. You can see dried leaf bases lost over the years. A different angle would have shown additional rooting along part of its length.

Aug. 10, 2018 This shows the center of gravity problem! Growing in the ground, such as the plants at Boyce-Thompson the crowns were supported by the ground and had a less pronounced ‘lean’. The desiccating leaves, especially the lower ones, is already well advanced here, to me indicating a lack of reserves having lost so many leaves over the years from which to draw, especially given that there is not any prominent ‘heart’ tissue.

Aug 23, 2018 looking a bit spindly as it leans back toward the pots center. The peduncle has much more widely spaced bracts.

Aug 26, 2018 the shriveling, desiccating leaves.

Aug 28, 2018 Here, along the upper half of the peduncle the bracts are separating as the secondary peduncles and buds emerge and develop.

Aug 30, 2018 The secondary peduncle nearly fully extended out with tertiary branching spreading the clusters of flower buds held in a crowded groups in umbels.

Sept 3, 2018 Where the secondary peduncles, branches, form the main peduncle, stem ‘zags’ slightly away giving it an alternating, spiraling form. Here you can see the base-up process of development as branching lengthens and buds mature.

Oct 27, 2018 The entire process has been slowing down, the flowers in the lowest ‘branch’ opening on Oct. 12. Here you can see my neighbor’s bees busy working the flowers, some of the long canoe shaped anthers split open and dehiscing their pollen. The overall structure of the inflorescence and the anthers provide the main visual ‘show’ when these bloom the corolla, or petal structure and perianth is secondary.

Growing this in a pot made perfect sense to me, but every decision carries consequences, not all of which I anticipated. Most Agave don’t form a ‘trunk’ growing its leaves, in a tight spiral, crowded along a very abbreviated stem, which adds little to its length to separate each consecutive leaf., but Agave colorata adds a little ‘extra’ slightly separating its leaves, resulting in a weak and kind of puny stem. If you’ve ever shuffled pots containing Agave more than a few years old, you understand that their crown, their substantial top growth, is relatively heavy, A. colorata is no exception, in fact their leaves each seem more substantial than leaves on many other similarly sized Agave. This results in a plant that as it grows begins to lean over, eventually, laying flat across the ground. As a Monocot the stems of Agave don’t caliper up over the years as does wood. These have no cambial meristem which would add secondary growth, and diameter, to the stem and as I said, with its relatively massive and heavy crown, it leans. This is the same characteristic that gives their small colonies their height.

![IMG_8077 The spring flush of growth on an Acer macrophyllum growing out of the tumbled basalt of the Columbia River Gorge in Memaloose State Park. Sapindaceae, Sapindales within the Rosids. Yes, the Aceraceae is gone and Maples are 'Roses'...not really, but they are cousins. "The maples have long been known to be closely related to the family Sapindaceae. Several taxonomists (including the Angiosperm Phylogeny Group) now include both the Aceraceae and the Hippocastanaceae in the Sapindaceae. Recent research (Harrington et al. 2005[2]) has shown that while both Aceraceae and Hippocastanaceae are monophyletic in themselves, their removal from Sapindaceae sensu lato would leave Sapindaceae sensu stricto as a paraphyletic group, particularly with reference to the genus Xanthoceras. Sapindaceae, Sapindales, Rosids](https://gardenriots.files.wordpress.com/2017/11/img_8077.jpg?w=223&resize=223%2C167#038;h=167)