The European Honeybee, EHB, and the Common Dandelion, are both ubiquitous in our modern urban lives though the one is portrayed as being both essential to our lives while its future is threatened and dependent upon our constant support. The Dandelion in contrast is a product of our disruption of the natural world and our very way of life and continues on as a pest species despite our efforts to ‘control’ it. They viability of the EHB is often linked to the continuation of a large population of Dandelion individuals. The EHB certainly benefits from the Common Dandelion finding ready individuals across our lawns and gardens, but the dandelion isn’t particularly dependent upon the EHB. The common dandelion, Taraxacum officinalis, is apomictic and doesn’t require pollinators at all. Apomixis isn’t a fancy word for ‘selfing’ or wind pollination either…what it means is that it, in lieu of an available pollinator, possess the capacity to skip over meiosis, the entire part of sexual reproduction in which an organism’s typical double, pair of chromosomes, which exist normally in all cells, and are known as diploid, ‘di’ for two sets of chromosomes, are reduced by half, to one set in ‘sexual’ cells, known as gametes, the sperm and egg cells, their chromosomes now ‘haploid’. Then, after pollination, the two haploid chromosomes are reunited uniquely through the process of fertilization. This is is the process skipped over in an apomictic plant. While it possess all of the ‘accoutrements’ of all flowering plants, stamen with their filaments and anthers, pistils with their stigma, style and fused carpels or ovaries, Dandelions are able to ‘short-circuit’ the process and produce viable seed on their own from their undivided, diploid, cells. Ever noticed how Dandelion seed heads always tend to be filled out? Perfectly spherical? Continue reading

Category Archives: Flowering

The Flowering of Monte: Going ‘Viral’ During a Pandemic

When will it actually flower? Once people got passed the, ‘What is ‘that’ question?’, this is what they wanted to know. When would it actually flower? by which they meant the individual petalous flowers open. More than a few times I responded snarkily…it’s flowering right now! Agave are among a wide ranging group of plants whose flowering includes a relatively large inflorescence, a supporting structure, which can rival the rest of the plant in terms of size. An Agave montana flowering here is foreign to our experience. The idea that such a large structure could arise so quickly, is to most people’s minds, strange, if not surreal…but for experienced gardens, who observe and strive to understand, there are links and connections, shared purpose and processes with all flowers. Gardeners and botanists, horticulturists and evolutionary scientists, they see the wonder in it all. When does flowering begin? When a plant commits to its purpose. Flowering should not be taken for granted. It does not occur to meet our aesthetic need. It is also much more than a simple result of a plant’s life. It is a fulfillment of one well and fully lived, projecting oneself into the future. Flowering and the production of one’s seed is a commitment to a future that will go on beyond oneself…and it begins from where every plant begins. Continue reading

Spreading the Wealth: Taking Advantage of Monte to Broaden a Teachable Moment

I’ve been taking advantage of people, striking when they are most sensitive, hungry for anything that is outside of their homes and families…I’ve been hanging informational signage amongst Monte’s floral neighbors as they come into bloom, not all of them. Some will remain anonymous like my Aristolochia semperivirens, an unassuming Dutchman’s Pipe, that is only noticed by the more discriminating of visitors. Others issue stronger ‘calls’ and so signage seems appropriate. Many people are taking the time to read them or take pictures of them for later consumption or to make sure they don’t forget. Many thank me for them. Who thought ‘school’ could be so cool! Anyway here is what I’ve hung out in the garden. Some will come down as their season ends, like the Pacific Coast Iris, others are waiting in the wings.

Agave montana

My Agave is flowering. The ‘spike’ you see growing upwards is the ‘peduncle’, the main flowering stem. As it meets its maximum height ‘branches’ will form near the top, from beneath the ‘bracts’, the tightly adpressed leaves, on which will form the yellow flowers. It will form a panicle, a ‘candelabra’ like structure. Agave are monocarpic, meaning they only flower once and then die, after it produces seed. It is 20 year old. Many Agave produce ‘offsets’ or ‘pups’ that can be grown on into mature plants…not this one!

This is a mountain species from Mexico’s Sierra Madre Orientale, where it is found between 6,000’ and 10,000’…not from the desert. This species is relatively new to the trade and was only formally described in 1996, 24 years ago. I’ve been told that this might be the first one to flower in the NW. Its native range experiences a temperate climate and receives its heaviest rains late summer-early fall during the hurricane season. It can experience freezing temperatures and even some snow there in open Oak-Pine forest. It begins its flowering process in Fall, then ‘stops’ for a period during winter, finishing the process in Spring/Summer. Most Agave are tropical/sub-tropical plants from deserts and are grown here in pots. There are 200 or so species, 3/4 of which are endemic to Mexico, found only there, none are native outside the Americas. Only 22 species are found in the US, from California into Nevada, Utah, Arizona, New Mexico and Texas. 3 are native to Florida.

Portland and the Maritime Pacific Northwest provide challenges to growing any Agave species and hybrid. Agave are native where climates tend to have most of their rainfall in summer. Here we have dry summers and wet cool/cold winters…this is the opposite of what most Agave need and will lead to rot and/or fungal foliar disease that can disfigure or kill most Agave species. Siting considerations are extremely important. They generally require full sun and excellent soil drainage. Here good air circulation helps foliage dry in winter. Sloping sites also help with soil drainage. Tilting the plant when planting is helpful as it helps the crowns stay dry. Some gardeners plant these under their eves or erect shelters over their plants to keep the crowns dry over winter. Agaves will require some summer water to grow well especially if they sit in dry soil all winter and spring….

Many Agave are becoming rare across their natural ranges in Mexico because of development and agriculture, a cause which threatens so much of our own natural flora in the US and around the world.

This species is not used to make Tequila! In its home range Agave are pollinated by hummingbirds, insects and nectarivorous bats, bats which are non-native here.

Beschorneria septentrionalis

(False Red Yucca)

There are seven species of Beschorneria, from forests of the higher mountains of Mexico down into Guatemala. This is the most northerly species occurring in NE Mexico, not far from the range of Agave montana. Unlike their cousins, the Agave, all but one of these are ‘polycarpic’, they can flower year after year. These form a substantial rhizome which spreads gradually when the plant is well sited, forming colonies. This one does so only slowly.

Another Asparagus family member, hardy through our zn8a, down to 10º for short periods, if you can keep the crown dry enough. This one struggles a bit and I have to remove a fair amount of rotting leaves every spring…I should move it and it would do better, but I haven’t…it wants better drainage. This particular site is a little wet close to our house which tends to concentrate rainfall a bit without any eave over hang to catch it.

As an open pine/oak forest dweller these are tolerant of relatively shady sites. Mine get some shade.

It’s inflorescence typically form these bright red stems with its sparse branching and hanging, narrow, bell shaped flowers. Part of their corolla is green.

At the top of my stone steps is a selection of another species, Beshorneria yuccoides ‘Flamingo Glow’, which has a buttery colored mid-rib on each leaf. from forests of the mountains of central/eastern Mexico.

Echium wildpretii

(Tower of Jewels)

There are 70 different species of Echium and several subspecies, in the same family as the commonly grown Borage. 27 species are endemic (occur no where else) to macronesia, the Canary, Madeira, and Cape Verde archipelagos lying in the eastern Atlantic close to Portugal, Morocco and west Africa. While the continental species are all herbaceous, dying to the ground over the winter, all but two of the island species are woody, with permanent stems. Echium wildpretii is one of these two.

Echium wildpretii can grow as high as 10’ in its home territory. It is generally a biennial, flowering in spring here, though sometimes, it can ‘wait’ and bloom the third spring. It is monocarpic, dying after producing seed. This plant is just under 9’ and is the tallest individual I’ve ever had in the 15 years of growing this. The plant grows in the ravines of Mount Teide, 12,198’, a volcano on Tenerife, 28ºN latitude, in the Canary Islands, so it has a very restricted range. It requires full sun and arid/dry conditions. With our much wetter winters it is best that you provide this with very good drainage as growing them in cold winter wet soil will decrease their cold hardiness and could lead to rot. Plant on south facing slopes and retaining walls with good air circulation. It is marginal, said to be hardy down to 23 °F.

The species E. pininana, the other Macronesian herbaceous grower, goes to 13’ having much the same form with blue flowers. E. candicans is a short lived woody shrub, which grows to 6’, both are grown here as well. In California these two and others are common some often escaping into the wild and crowding out native species. Here, these are marginal and survive only in protected areas killed by normal to colder winters.

Check my blog at Garden Riots. Annie’s Annuals sells several of these: https://www.anniesannuals.com/search/?q=echium

Grevillea x ‘Pink Pearl’

Grevillea is a genus of 360 species of flowering plants native to Australia and north and west to the Wallace Line. They vary from ground huggers to a tree over 100’ tall. They belong to the Protea family which includes many bizarre and large cut flowers used in the florist industry. They are pollinated by many Lepidoptera, butterflies and moths as well as by Honeyeaters, a group of nectar feeding birds native to their home range related to South African Sunbirds, but not at all to our Hummingbirds. Hummingbirds and bees visit these here.

Most Grevillea are not hardy here in the NW so choose judiciously. To find reliable plants check out the offerings of Xera Plants on SE 11th and or take the trip out Sauvie Island to Cistus Nursery, they have a section of Australian plants. There is a great review of NW hardy Grevillea at Desert Northewest’s site, https://www.desertnorthwest.com/articles/grevilleas_revisited.html

Grevillea readily hybridize. This is thought to be a hybrid of G. juniperina x G. rosmarinifolia. If you give it what it wants it is hardy down to 20ºF, maybe lower. I planted this one 6 years ago here. One winter, ’16/’17, I lost about 1/3 of the top. That was Portland’s fifth coldest winter ever in terms of number of days with freezing temperatures…so not typical. (https://weather.com/storms/winter/news/portland-oregon-worst-winter-city-2016-2017) I suspect another degree colder or with another day of sustained freezing, I would have lost the entire plant.

These are relatively fast growing and can take a hard pruning. In Australia these are often used as hedge plants causing them to grow densely with their pokey needles, quite a barrier! I prune mine regularly to limit its size while retaining its softer look with drooping branch tips.

These are sun lovers and require well drained soil here. They are drought tolerant in the Pacific NW requiring no water after establishment. It is essential that should you choose to fertilize that it include NO PHOSPHOROUS!!! Phosphorous is plentiful in our soil already and adding anymore can prove deadly to Grevillea and also to most all members of the larger plant family. These come from regions with phosphorous poor soils and are very well adapted to searching it out, so…don’t add any!

x Halimiocistus wintonensis ‘Merrist Wood Cream’

This Rock Rose is a hybrid between two different genera Halimium and Cistus, a relatively rare even as species from different genera aren’t generally capable of crossing successfully. The parents are both Mediterranean plants and this plant benefits from growing under like conditions, warm to hot, dry summers and cool/mild and relatively wet winters.

This plant has grown here for 10+ years on this south facing slope in unamended soil. It benefits from a light cutting back after flowering to help keep it compact and to keep it from falling/splaying open. All of the Rock Roses have a tendency to splay open with time here as our rich soil tends to push them to produce extensive soft growth. Don’t cut these hard, below healthy growth, if you do you are likely to end up with dead stubs unable to resprout. I’m planning to take cuttings of this, root them and replace this plant as it has gotten rather ‘leggy’ over time.

There are many fine Rock Roses available from these two genera that can be grown here.

Lobelia laxiflora ssp. angustifolia Heavy with bloom this Lobelia began flowering almost a month ago.

Lobelia laxiflora ssp. angustifolia

This Lobelia, with its narrow hot red tubular flowers, from Mexico, is reliably evergreen here except over our coldest winters, which can kill it to the ground, but from which it springs back. It often blooms for 7 months or more in the year. As you might guess it is attractive to hummingbirds. This plant is rhizomatous and in too good of conditions with summer water, has a tendency to spread, though it does so compactly. It is better ‘behaved’ under drier, more spare, conditions.

Lobelia are a large and varied genus with 415 species occurring primarily in tropical to warm temperate regions. I also grow the less commonly grown species type, sometimes called ‘Candy Corn Flower’ with broader leaves which is less robust for me here, but showy in its own way.

I grow Lobelia tupa on the east side of our house. It’s a large growing Lobelia from the Andes of Chile with hooking dark red large flowers. I have others on my list including the large pink flowering species, L. bridgesii, to acquire and am somewhat enamored with the ‘Tree Lobelias’ limited to the Hawaiian Islands.

Mimulus aurantiacus ‘Jeff’s Tangerine’

Sometimes known as “Sticky” or “Bush Monkey Flower” this plant is native from SW Oregon down through most of California into Baja. A ‘sub-shrub’ this has a somewhat woody base from which sprouts softer herbaceous stems that carry the leaves and flowers. Found from coastal bluffs east into the Siskiyou and Sierra Nevada mountains, these are ideally suited to our mediterranean climate with its summer dry/winter wet precipitation pattern.

Typically, where I’ve seen it growing in situ it is taller than my plant with a much more substantial woody base. At Point Lobos, on the central California coast, these can be over 4’ tall and form impenetrable thickets. Here with our rich soil it grows more lushly and flops. My plant is ten years old and will bloom all May through September in waves, almost never completely out of flower.

Place it in full sun. Mine receives only sporadic summer water. It grows in unamended soil on a south slope so it has good surface drainage. It benefits from free air movement and good soil drainage. There are several color forms available from specialty nurseries.

Pacific Coast Iris

(aka. pacifica)

There are 12 Iris species in the group native to our region stretching from southern California northward into Washington state, in a narrow band between the ocean and the Cascades and into California’s western Sierra Nevada. Most of these are limited to California and southern Oregon to areas that receive enough rain and are often limited to places closer to the coast. The Willamette Valley and Washington is mostly limited to one species, the deciduous, woodland edger, Iris tenax.

Hybridizers have taken advantage of their tendency to cross and are found in a wide range of jewel like colors, white, to yellow, red, russet, blue and purple. The hybrids are evergreen. These must generally be searched out as their production is relatively low because these Irises are difficult or impossible to grow anywhere else in the country because of soil and climate differences too far out of their ability to adapt.

The hybrids are drought tolerant in our western gardens. Plant them with plenty of sun, then water to establish. Don’t plant them anywhere where the soil remains soggy into the summer, they need to dry out. It is important to leave them undisturbed after planting. If you choose to move or divide them, wait until the fail rains, when they are producing new roots. They will likely die if messed with during the summer. See my blog: gardenriots.com.

Sphaeralcea x ‘Newleaze Coral’

(Glog

The genus Sphaeralcea is native/endemic to the intermountain west of North America, occurring between the Rocky Mountains and the Cascades and east of the Coastal mountains of California. Some can be found in eastern Washington, Oregon and Idaho on south into northern Mexico. They like sun, heat and thrive in poorer mineral soils and are drought tolerant here once established.

‘Newleaze Coral’ earned its garden pedigree in the UK and is a stellar performer here in xeric beds. Sphaeralcea is a member of the large Mallow family which contains 244 genera with 4,225 known species. Well-known members of economic importance include okra, cotton, cacao and durian. There are also some genera containing familiar ornamentals, such as Alcea, Hibiscus, Malva and Lavatera, as well as the genus of trees, Tilia. Commonly called Globe Mallows, this Sphaeralcea will easily bloom for 5 months bookending the summer months.

The Flowering of Monte, Social Media and the Hordes

Where has the last month gone??? This is a brief, I promise, update to those of you who’ve been following the flowering of Monte, my Agave montana, this spring. Ever since Monte went viral on social media, life has been a little crazy here. On April 20th the bracts at the top of the inflorescence separated enough that I could see down inside to the tightly clustered buds below looking a lot like a bunch of chicks with their beaks upheld…then the changes became visible, changing noticeably on a daily basis…and everyone began to see it. Our regular walkers in the neighborhood, bicyclists, commuters and the many who’s regular workdays brought them by…and I swear everyone of them must have been posting!

-

One flower, from the stigma tip to the bottom of the ovary and pedicel attaching it. -

Each of these pillow like structures are a good 12″ across, 8″ wide and 7″ tall.

It did not take long at all before Monte became a destination. Facebook, Instagram, Reddit, Next Door, Monte’s evolving visage was appearing everywhere and the number of visitors, which was at one time early on easy to handle, quickly began to approach sideshow numbers and atmosphere. Many seemed to have completely forgotten about the pandemic and sheltering in place. What was once a varying stream flow became a flood. I would go outside to take pictures, make notes and measure, ever earlier, as early as 5:30am, and people would be here, for Monte. At first I would ‘hold class’, answer their questions and try to educate them about the processes of plant growth, the thumbnail version, and people seemed genuinely curious. I tried to take advantage of what I saw as a ‘teaching moment’…but, the numbers quickly increased and many seemed more interested in snapping their IG pics and getting in on this event. But this event wasn’t like the one day happening of last year’s eclipse or the brief period of the blooming Corpse Flower up on the WSU campus…but people came like this would be their only chance. Continue reading

Gardening in Public, Charismatic Mega Flora and the Need for a Public Horticultural Intervention

We ‘need’ charismatic mega-flora today, plants that scream out to even the most plant blind of us to take notice, those that create such a sudden and uncontrollable ‘stir’ within us that our simple glimpse of them breaks our momentum, our chains of thought, interrupting whatever we’re doing in that moment bringing about a reflexive interjection, cause us to take notice, create an uncontrollable urge to stop what we’re doing and come back for a closer look! To tell our parents, partners or friends, to drag them back, for a repeat performance or to see if what we saw is really there or merely a mistake of perception. And they do come back. I see them every day, sometimes dragging disinterested friends to see this unimaginable impossibility. I hear them when I’m out working in the private part of the garden with excited voices, sometimes expletives, “Look at this ‘F@#$ing’ thing! Can you believe it?” I love this. They’ve come for ‘Monte’!

-

Checking on my latest science experiment. credit Doreen Winja -

At this point: the rosette remains about 6′ in diameter, overall height is 13′ 4″, the circumferance averages about 43″ around the swelling terminal end which is about 30″ tall itself. I’m 6’2″ and I’m on a 10′ orchard ladder. credit Doreen Winja -

The flower buds rising out from behind the bract on its secondary peduncles, branches, after having emerged from what looks like a ‘red’, raddichio colored envelope, showing between the buds and bract.

COVID-19, Pandemics and How They Will Change the World For the Better

I’m not a biological ‘fatalist’, but there are several reasons why epidemiologists were attempting to plan for a pandemic and why the Obama administration was empowering institutions, creating protocols and organizing resources that could be mobilized quickly, before the COViD-19 outbreak, not for this one specifically, but one of some kind. Viruses, bacteria, mycoplasma and other microbes fill the world at a microscopic level…they are everywhere, all of the time. Our own bodies contain far more of them than we do of our own some three trillion cells. Fortunately, most of them do not cause us disease, at least as long as we remain healthy. Many of them, in fact perform valuable functions in us, beneficial ones, without which our lives would be the poorer. Disease too is part of life’s ‘plan’. Its agents are dynamic. Today’s diseases are not those of the past. We evolved together. They mutate and sometimes ‘leap’ across species boundaries. A study of biology and disease reveals a function of disease or at least a consequence to the health and evolution of a species. It may sound heartless to put it this way, but disease is very much a part of living. With this new disease, COVID-19, as with others, it is selective, affecting those whose health is compromised in some way disproportionately, killing those most susceptible, the weak and those may include those surprising to us. As in most things concerning life, nothing is so simple as our concept of strong and weak. Disease is a part of the process of natural selection that has always been in effect in the world. Continue reading

Agave montana: Monte’s Flowering Attempt…and What’s Behind It

It’s October in Portland and my Agave montana is in the process of flowering…I know, we’re heading toward winter, with its rain and average low down into the mid-30’s with potentially sudden damaging temperature swings from mid-November into March dropping below freezing to the low twenties, with extremes some years, generally limited to the upper teens, though historically, some areas have dropped into the single digits, those Arctic blasts from the interior….Winter temps here can be extremely unsupportive of Agave’s from ‘low desert’ and tropical regions. Combined with these cool/cold temperatures are our seasonal reduction in daylight hours and its intensity (day length and angle of incidence varies much more widely here at 45º north) and the rain, ranging from 2.5″ to 6″+ each month here Nov.- Mar., resulting in a ‘trifecta’ of negative factors which can compromise an Agave, even when in its long rosette producing stage. Any Agave here requires thoughtful siting with special consideration for drainage, exposure and aspect. For an Agave, conditions common to the maritime Pacific Northwest are generally marginal, yet I am far from alone in my attempts to grow them here. Previously, in April of 2016 I had an Agave x ‘Sharkskin’ flower, a process that spanned the summer months, taking 7 until mid-October to produce ripe seed. I was initially a little pessimistic this time about A. montana’s prospects. Why, I wonder, if plants are driven to reproduce themselves would this one be starting the process now? Continue reading

Agave colorata and its Blooming Attempt in ’18

Agave colorata before flowering initiation, growing nearly horizontal, with a broadly cupped lower leaf holding water. From the Irish’s book, “Agaves, Yuccas and Related Plants”, “The leaves are 5-7″ wide and 10″-23” long [mine were all at the small end of this range] They are ovate ending in a sharp tip….The leaves are a glaucous blue-gray and quite rough to the touch. The margin is fanciful with strong undulations and large prominent teats of various sizes and shapes. A very strong bud imprint marks the leaves, which usually are crossbanded, often with a pink cast [not mine], and end in a brown spine 1-2 in. long.

interest, their leaf color, substance and sculptural qualities, the margins of its broad, thick leaves, with their rhythmic rounded ripples, each tipped with a prominent ‘teat’ and spine. This is not a large plant, typically growing 23″- 47″ in diameter and my plan was always to keep it in a pot as it is from coastal areas of the Mexican state of Sonora, found sporadically in a narrow ‘band’ south into Sinaloa. Agave colorata is very rare and uncommon in nature and growing on steep slopes of the volcanic mountains in the coastal region in Sinaloan thornscrub. It often emerges from apparently solid rock cliffs sometimes clinging high above the water below.

Growing in Sonora and at Home

It is poorly adapted to our wet winter conditions though it is reputedly hardy into USDA zn 8, or as low as 10ºF. Its natural northern limit is thought not due to cold, but by excessive aridity in the northern parts of Sonora. I didn’t test it, leaving it outside under the porch roof, bringing it in when forecasts called for below 20ºF, as any plant is more susceptible to cold with its root zone subject to freezing. With perfect drainage and overhead protection, you might be able to get away with this in the ground, but the combination of significant wet with our cold is likely too much…still if someone wanted to try….At best I suspect this one would still suffer from fungal leaf diseases, disfiguring the foliage.

This is usually solitary, but it can be found occasionally in small clumps/colonies up to nearly 10′ across, pushing up against each other on their slowly growing and short ‘trunks’ to 4′ high. My plant produced just a few pups over the first third of its life.

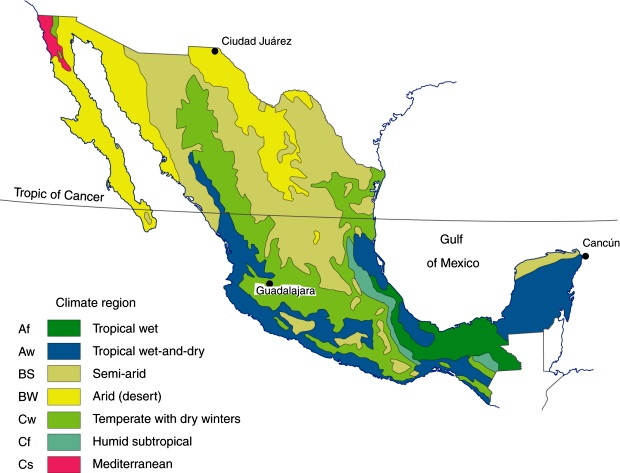

I wanted to include a climate map of Mexico. This one utilizes the classic Koppen system designating the various climates based on temperature and precipitation and their seasonal patterns. Here it has been modified by Mexican climatologists to better reflect Mexico’s complicated geography…even so, because of the abrupt changes in elevation, and land forms, different climatic conditions can occur in close proximity to one another. Mountains can create wetter and drier areas that on a map of this scale are lost.

Sonora has three distinct geographic areas all running along a ‘line’ from the northwest toward the southeast, the Gulf of California and its associated coastal landscape paralleling the Sierra Madre Occidental, sandwiching plains and rolling hills in the middle. The coast and plains/rolling hills are arid to semi-arid, desert and grasslands, while only the higher elevation of the easterly mountains receive enough rain to support more diverse and woody plant communities, scrub and Pine-Oak forests.

This map comes from the Arizona Sonoran Desert Museum. The link takes you to one of their pages which discusses the natural history of the desert, thornscrub and tropical deciduous forest of Sonora.

This region also varies north to south, the climate drying as you go north into the Sonoran Desert. Moving south on down into Sinaloa, and further, is the some what wetter ‘dry deciduous forest’ biome with an array of woody leugumes, including several Acacia. Agave colorata resides in the transition zone in between, in the portion of ‘thornscrub’ near the Sonoran/Sinaloan border. North and south the Thornscrub itself changes in composition. The Sinaloan Thornscrub serves as a transition zone between the desert and the slightly wetter, taller growing, Tropical Deciduous Forest that continues the south. All along this band running north on into Arizona’s Sonoran Desert are various columnar cactus a food source for Mexico’s migrating nectarivorous bat species. It is a unique flora community, containing species from bordering floral regions and other species unique or endemic to this transition zone itself. The area continues to be under threat, primarily by cattle ranching that moved into the region in the ’70’s and ’90’s bringing with it clearing and the introduction of non-native and invasive Bufflegrass, Pennisetum ciliare, also known under its syn. Cenchrus ciliaris, for pasture. Bufflegrass is also a serious problem north into Arizona. In Sonora many of the cleared woody species have since begun moving back in, while the smaller, more sensitive species have not. Climate change promises to further squeeze it. (The World Wildlife Fund maintains a website with good descriptions of many eco-regions I sometimes find it very helpful when trying to understand the conditions of a plant I’m less familiar with.)

When growing plants like this, one should keep in mind the concept of heat zones. The American Horticultural Society has created a map of the US delineating its ‘heat zones’. It is based on the average number of days an area experiences temperatures over 86ºF. At that temperature most plants begin to shut down their metabolic processes…they slow their growth. Check out the AHS map (AHS US Heat Zones pdf.) and keep in mind that we are warming up! The AHS map has us, Portland, OR, in zone 4, meaning we experience 14-30 days with highs over 86ºF each year. Last summer, ’18, we actually had a record 31 days over 90ºF! Now consider that the coastal/plains region of Sonora likely experiences between 180-210 such days! Agave colorata may not need this, but it is certainly adapted to such a level of heat stress. Something to think about, especially when you consider that we receive the bulk of our rain over the winter when our daily highs and lows average for Nov. 40º-53º, Dec. 35º-46º, Jan. 36º-47º, Feb. 36º-51º and Mar. 40º-57º…keeping in mind that we could freeze on most any of those dates. The Sonoran Desert receives its minimal rainfall in a summer/monsoonal pattern….This is why bringing such ‘low desert’ plants to the Pacific Northwest can add another degree or two of difficulty to your success!

Growing this in a pot made perfect sense to me, but every decision carries consequences, not all of which I anticipated. Most Agave don’t form a ‘trunk’ growing its leaves, in a tight spiral, crowded along a very abbreviated stem, which adds little to its length to separate each consecutive leaf., but Agave colorata adds a little ‘extra’ slightly separating its leaves, resulting in a weak and kind of puny stem. If you’ve ever shuffled pots containing Agave more than a few years old, you understand that their crown, their substantial top growth, is relatively heavy, A. colorata is no exception, in fact their leaves each seem more substantial than leaves on many other similarly sized Agave. This results in a plant that as it grows begins to lean over, eventually, laying flat across the ground. As a Monocot the stems of Agave don’t caliper up over the years as does wood. These have no cambial meristem which would add secondary growth, and diameter, to the stem and as I said, with its relatively massive and heavy crown, it leans. This is the same characteristic that gives their small colonies their height.

Puya: Growing These Well Armed South Americans in the Pacific Northwest

[I wrote this originally about 2 years ago as part of what turned out to be a too long look into the Bromeliad Family. Here I present only the genus Puya spp. in an edited form with the addition of the species Puya berteroniana. Go to the original article to read about the shared evolution of the several genera and families that comprise the family, why these are not considered succulents and a look at the armed defenses of many plants. My plan is to breakout at least some of the other genera as well as I think the length of the original post may have put some readers off.]

Puya: one of the Xeric Genera of Terrestrial Bromeliaceae

The name “Puya” comes from the Mapuche Indian word meaning “point” (The Mapuche people are indigenous to Chile and Argentina. They constitute approximately 10% (more than 1.000.000 people) of the Chilean population. Half of them live in the south of Chile from the river Bío Bío to Chiloé Island. The other half is found in and around the capital, Santiago and were mostly forced to the city after Pinochet privatized their lands giving them to the wealthy.)…the assignation is clear and the pointed, spiky, nature of this genus is immediately obvious to anyone. But there is something easy and comfortable about the sound of the word in your mouth when you speak it…poo-‘yah. Puya are native to the arid portions of the Andes and South American western coastal mountains. (Oddly, two species are found in dry areas of Costa Rica.)

Puya spp., populate arid western regions of the Andes Mountains up into southern Central America. These are terrestrial plants, relying on their roots to find the moisture that they need. They possess the same basic rosette structure common to all members of the Bromeliad family to which they belong, including their petiole-less leaves, which clasp directly to a compact stem structure, funnelling the infrequent, and seasonal, precipitation they get into their crowns and root structures where they can take it up, a strategy very similar to Agave and Aloe which grow under similar conditions. Continue reading

Ginkgo biloba: on reproduction, evolution and anomalous existence

There are six Ginkgo trees here along Main St., on the north side Chapman Square, downtown, they are the most abundant species on the two blocks and the smelly not-a-fruits that drop in the fall demonstrate that many of them are female.. You can see the Elk fountain, one of several fountains once installed so locals could ‘water’ their horses. Only two the Ginkgos on the two blocks are male clones that I know of, the others are a mix of male and female seedlings. The male strobili are still in evidence on the trees. The female trees appear to hold their strobili on higher branches, as I could see nothing on the available lower branches with my bad eyes.

Mid-April and the Ginkgos are flowering….well, technically not ‘flowering’, because they aren’t angiosperms. Botanically speaking, they are doing what they do instead, forming the little structures that contain their sex organs for what would most likely be failed attempts at reproduction. Think about it, in a community filled with males no progeny will be produced. We were on one of our walks down an inner section of Tri-Met’s Orange Line, approaching the Tilikum Bridge, when I noticed this event…I was a little surprised.

If you know much about Ginkgos you probably know about their fruit, which again is not technically a ‘fruit’. Only angiosperms, true ‘flowering plants, form ‘fruit’. The Ginkgo’s ‘fruit like’ structures are notoriously stinky when they become ripe, smelling like what many describe as being similar to dog ‘poo’, others liken it more to ‘vomit’, either equally unpleasant, when they fall to the ground and splatter or are stepped on…one of the reasons why these trees are cloned, grafted, by the nursery industry….By cloning selected forms propagators allow us to remove the chance of purchasing a female tree…unless in their zeal to bring a particular form to market they select a tree that hasn’t flowered yet….Without looking at their chromosomes, it is nearly impossible to determine the sex of a juvenile tree. Clones stay true to their sex, so if their scion wood, or buds, are taken from a male tree, the result will be a male clone. Ginkgos are a dioecious species, ‘di’ meaning two, so any one individual plant produces only male or female structures, so it takes two trees, of opposite sex, to produce viable seed. Monoecious means that an individual plant produces male and female structures. In Ginkgo spp. and the non-flowering gymnosperms these sexual structures are called stobili or singularly, a strobilus. Continue reading