Long ago I took a couple philosophy classes at U of O; one on existentialism, in which we read several novels and discussed their themes; and another, an upper division, class on ethics, because I was curious…I dropped the ethics class after sitting around the table in seminar discussing particular authors’ thoughts, like Kierkegaard and Butler. Majors seemed to take pleasure in making fun of what I got from them in discussions. Hated this. I still have trouble reading philosophy. It seemed like a game to them in which they argued a position to show off their cleverness, their superiority, the ideas themselves of relatively little importance…while hiding their biases. It must have been so self-assuring for them to ‘know’ these author’s precise thoughts and bash those who don’t get it…or saw something different (like the newbie, me). To quote someone isn’t to understand, it is only miming, presumably in hope of getting a reward. I read for understanding. It’s not a competition. So, this book, “Determined: A Science of Life Without Free Will”, taking a science approach to evaluate a philosophical concept, was difficult to begin. The author, neuro-biologist Robert Sapolsky, argues that those philosophers and theologians who claim that people have free will to do whatever they desire or set their minds to, are wrong. This appealed to me immediately. Continue reading

Long ago I took a couple philosophy classes at U of O; one on existentialism, in which we read several novels and discussed their themes; and another, an upper division, class on ethics, because I was curious…I dropped the ethics class after sitting around the table in seminar discussing particular authors’ thoughts, like Kierkegaard and Butler. Majors seemed to take pleasure in making fun of what I got from them in discussions. Hated this. I still have trouble reading philosophy. It seemed like a game to them in which they argued a position to show off their cleverness, their superiority, the ideas themselves of relatively little importance…while hiding their biases. It must have been so self-assuring for them to ‘know’ these author’s precise thoughts and bash those who don’t get it…or saw something different (like the newbie, me). To quote someone isn’t to understand, it is only miming, presumably in hope of getting a reward. I read for understanding. It’s not a competition. So, this book, “Determined: A Science of Life Without Free Will”, taking a science approach to evaluate a philosophical concept, was difficult to begin. The author, neuro-biologist Robert Sapolsky, argues that those philosophers and theologians who claim that people have free will to do whatever they desire or set their minds to, are wrong. This appealed to me immediately. Continue reading

Otherlands: A Journey Through Earth’s Extinct Worlds, a Valueable Entry into Understanding This World

The Rediscovery of America: Native Peoples and the Unmaking of U.S. History, a review

Ned Blackhawk’s book, “The Rediscovery of America: Native Peoples and the Unmaking of U.S. History”, is not just another history of the clash between European colonizers and Native peoples. It is a book of relationship, how over time, this country has gained much of its current and evolving form, from the extended conflict between us and native peoples, from their refusal to acquiesce, who have instead demanded that this country recognize native sovereignty and honor the treaties made between us, treaties which, along with our Constitution, are the ‘supreme law of the land’. Some of the most momentous changes to this country, its policies, laws and court decisions, resulted from these ongoing conflicts and this country’s attempts to resolve them. I was unaware of this book, and Blackhawk, until I read a review he wrote of Hamalainen’s, “Indigenous Continent” which I’d just finished. Continue reading

Ned Blackhawk’s book, “The Rediscovery of America: Native Peoples and the Unmaking of U.S. History”, is not just another history of the clash between European colonizers and Native peoples. It is a book of relationship, how over time, this country has gained much of its current and evolving form, from the extended conflict between us and native peoples, from their refusal to acquiesce, who have instead demanded that this country recognize native sovereignty and honor the treaties made between us, treaties which, along with our Constitution, are the ‘supreme law of the land’. Some of the most momentous changes to this country, its policies, laws and court decisions, resulted from these ongoing conflicts and this country’s attempts to resolve them. I was unaware of this book, and Blackhawk, until I read a review he wrote of Hamalainen’s, “Indigenous Continent” which I’d just finished. Continue reading

The Dawn of Everything: The History of Humanity; a Review

David Graber, an anthropologist, and David Wengrow’s, an archeologist, book, “The Dawn of Everything: A New History of Humanity”, is more than ‘just’ a history of humanity, which would on its own suggest a massive tome of thousands of pages. it is an examination of how we ‘do’ history drawing many examples of peoples and societies across time from the Paleolithic through the colonization of North America. It is not simple reportage, rather a look into the correctness or accuracy, of how we have been telling history. I enjoy such questions and their capacity to rock the academic and intellectual ‘boat’. My reading has spurred the formation of links to two other books I’ve read recently, Stephen Jay Gould’s, “The Burgess Shale” and Pekka Hamalainen’s, “Indigenous Continent”. All three of these call into question previously widely accepted thinking on their subjects. More than this, they question foundational ideas upon which the science they examine are founded. This appeals to me. But more than this, there is an idea central to them all which really rings ‘true’ for me. Continue reading

David Graber, an anthropologist, and David Wengrow’s, an archeologist, book, “The Dawn of Everything: A New History of Humanity”, is more than ‘just’ a history of humanity, which would on its own suggest a massive tome of thousands of pages. it is an examination of how we ‘do’ history drawing many examples of peoples and societies across time from the Paleolithic through the colonization of North America. It is not simple reportage, rather a look into the correctness or accuracy, of how we have been telling history. I enjoy such questions and their capacity to rock the academic and intellectual ‘boat’. My reading has spurred the formation of links to two other books I’ve read recently, Stephen Jay Gould’s, “The Burgess Shale” and Pekka Hamalainen’s, “Indigenous Continent”. All three of these call into question previously widely accepted thinking on their subjects. More than this, they question foundational ideas upon which the science they examine are founded. This appeals to me. But more than this, there is an idea central to them all which really rings ‘true’ for me. Continue reading

Knapweeds in Redmond’s Dry Canyon and the Pursuit of a Healthy Landscape

Redmond’s Dry Canyon looking south from the west rim on the Maple Street Bridge. The area in the immediate foreground burned this last summer.

If you garden, or maintain a landscape, you come to understand that not all weeds are the same. Each will have its own ‘strengths’, or perhaps you might call it ‘virulence’. Any particular weed, just like any other plant, will respond ‘positively’ to supportive growing conditions, conditions which often closely align with those which exist in its place of origin. Plant explorers and nursery growers are always looking for ‘new’ plants for landscape use. in a way, they have to walk a fine line. They must find plants, that with reasonable effort on the part of the gardener, can thrive across a range of conditions, unless they are looking for specialty plants, for narrow, niche, markets. The introduction of new plants must be somewhat measured, our enthusiasm tempered, because plants which are too adaptable, too vigorous, may possess the ability to escape our cultured gardens and find a place in the surrounding, uncultivated, landscape.

For Central Oregon, when we look beyond our regional natives, we must keep this in mind. Exotics from similar growing and climatic regions around the world offer both promise and threat. We want our plants to be successful, but not too. Sometimes through the process of trade, the movement of livestock and agricultural products, particularly aggressive species hitch a ride. A few weed seeds can be easy to miss. If they are aggressive enough and go unnoticed, a distinct possibility, it is likely that they wont be detected until a sizable local population asserts itself…and if no one is watching, that can be a fateful error. One group of plants, with many wonderful possibilities, also include species which can be exceedingly problematic here in Central Oregon, these are from regions sometimes referred to as Steppe. Continue reading

On Weeds, Disruption and the Breaking of Native Plant Communities: Toward a More Informed Working Definition of Weeds

The bottom land in Redmond’s Dry Canyon was used for decades as low quality pasture, the native community pretty much obliterated. Those areas with surface rock are more likely to retain more of the original plant community, although Cheatgrass has invaded much of those areas as well. The is looking southerly over one of the larger ‘pasture’ areas near the disc golf course. There is very little Cheatgrass through this section south of West Rim Park. It includes a few native seral species which typically occupy disturbed sites as a site transitions, including Gray Rabbitbrush you see here. Found in this area too is Secale cereale, Annual Rye, a non-native, which appears to have been planted along more formal paths to limit Cheatgrass spread(?). Junipers are moving in. Sagebrush hasn’t yet.

It is commonly said that a weed is a plant out of place…and of course ‘we’ are the one’s who decide this. Some will try to argue that there are no weeds, that all plants belong and if we only left weeds alone landscapes would reach a balance on their own. If one’s time frame is long enough this may be the case, though this will take considerably longer than one of our lifetimes, and then there is our inability to actually leave landscapes on their own, or to at least consciously moderate our disturbance of them. Weeds are plants. They are not a separate classification of plants. They are plants removed from their places of origin and released into another where they have competitive advantages. Most people still simply tend to refer to plants they don’t like or want as weeds. These positions are at odds with one another. This leads to confusion and a lack of clarity, undermining any urgency to take action.

Weeds have become ‘personal’, their status a matter of ‘opinion’….A weed is a weed only if “I” agree that it is, or perhaps some ‘expert’, such as when agricultural scientist identify them as an economic threat to farms and label them as ‘noxious’. Without agreement and urgency there is a tendency to do nothing about them. Plants in general are attributed little intrinsic value. For many people they are just there. Native plants we vaguely understand as belonging to a place, but most people would be hard pressed to identify and name many at all. Quite different species are often lumped together, their relationships unnoticed. Natives are reduced to being ‘background’, their status reduced to decoration, attractive or not, a ‘space’ filler, perhaps a hinderance to what we would chose to do with a place. Continue reading

Indigenous Continent: The Epic Contest for North America, A Review

We live today in a very divided and polarized world. You can take almost any characteristic used to define a group of people today and it is now being used to separate and divide. We do this sometimes out of pride, others, out of fear and desperation. We thus define our individuality, or our ‘people’, in a process of reduction, eliminating variation and possibility. This is who I am. This is my world, the world that matters. When we do this our world shrinks. That outside of it, becomes a threat and ‘threats’ proliferate. The causes of our problems are commonly reduced to ‘them’. Most of the divisions are, however inconsequential. Having been pried open we find ourselves separated by seemingly giant rifts, animosities greatly exaggerating the actual differences. Too many ‘leaders’, in bids to gain power themselves and cement their own advantage, beat the drums of division, gaining followers, customers and believers to their cause…which is often something very different than what they may publicly say. A world built on such differences is a precarious one, as groups strive for security by focusing on the differences rather than on the infinitely more common shared links which join us. This country was, in many ways, built on such differences. Continue reading

We live today in a very divided and polarized world. You can take almost any characteristic used to define a group of people today and it is now being used to separate and divide. We do this sometimes out of pride, others, out of fear and desperation. We thus define our individuality, or our ‘people’, in a process of reduction, eliminating variation and possibility. This is who I am. This is my world, the world that matters. When we do this our world shrinks. That outside of it, becomes a threat and ‘threats’ proliferate. The causes of our problems are commonly reduced to ‘them’. Most of the divisions are, however inconsequential. Having been pried open we find ourselves separated by seemingly giant rifts, animosities greatly exaggerating the actual differences. Too many ‘leaders’, in bids to gain power themselves and cement their own advantage, beat the drums of division, gaining followers, customers and believers to their cause…which is often something very different than what they may publicly say. A world built on such differences is a precarious one, as groups strive for security by focusing on the differences rather than on the infinitely more common shared links which join us. This country was, in many ways, built on such differences. Continue reading

Wonderful Life: The Burgess Shale and the Nature of History, A Review

I am a newbie to the writing of Stephen Jay Gould, a paleontologist who has attracted a sizable share of critics and detractors for his reasoned and outspoken views on our understanding of evolution, the history of science, humanism and ‘Man’s’ place in the overall scheme of things. I find this book an ‘eyeopener’. Previously my education on the topic of evolution has been casual, incidental, social, something I’ve observed and absorbed as a product of living my own life, a book here and there, not formal or studied. Over the last ten years or so I have been more focused on the science of life, that defining ‘force’ which animates all organisms, what it is to be alive at a time when the traditional divisions between the sciences, particularly between physics, biochemistry, what has come to be known as ‘systems science’ and cell biology are beginning to dissolve and merge. Science continues down its more traditional pathways with its atomistic, reductionist, approach, which has dominated most of the accepted work up until today. Under the ‘old rules’ scientists utilize what we understand as the ‘scientific method’ in which they conduct ‘controlled’ experiments, repeatedly, to understand a particular action or process. Such demand for control leads them to break problems down into limited, often tiny ‘bits’, in which it is more easy to examine and evaluate a single isolated process with ‘confidence’. Others then assemble all these bits that they’ve learned into a theory of the whole. Traditionally conducted science works from the idea that we can understand the whole by studying a problem in its parts, often ever more minute. While this has proven to be a very valuable strategy, improving our understanding, shaping the way we act in the world and our technologies, it has also become more evident that this approach has left something out, that by limiting our examination of life in this way we are missing something essential. What actually constitutes life? The study of life’s origin and its evolution expose the shortcomings of relying on this approach alone. Continue reading

I am a newbie to the writing of Stephen Jay Gould, a paleontologist who has attracted a sizable share of critics and detractors for his reasoned and outspoken views on our understanding of evolution, the history of science, humanism and ‘Man’s’ place in the overall scheme of things. I find this book an ‘eyeopener’. Previously my education on the topic of evolution has been casual, incidental, social, something I’ve observed and absorbed as a product of living my own life, a book here and there, not formal or studied. Over the last ten years or so I have been more focused on the science of life, that defining ‘force’ which animates all organisms, what it is to be alive at a time when the traditional divisions between the sciences, particularly between physics, biochemistry, what has come to be known as ‘systems science’ and cell biology are beginning to dissolve and merge. Science continues down its more traditional pathways with its atomistic, reductionist, approach, which has dominated most of the accepted work up until today. Under the ‘old rules’ scientists utilize what we understand as the ‘scientific method’ in which they conduct ‘controlled’ experiments, repeatedly, to understand a particular action or process. Such demand for control leads them to break problems down into limited, often tiny ‘bits’, in which it is more easy to examine and evaluate a single isolated process with ‘confidence’. Others then assemble all these bits that they’ve learned into a theory of the whole. Traditionally conducted science works from the idea that we can understand the whole by studying a problem in its parts, often ever more minute. While this has proven to be a very valuable strategy, improving our understanding, shaping the way we act in the world and our technologies, it has also become more evident that this approach has left something out, that by limiting our examination of life in this way we are missing something essential. What actually constitutes life? The study of life’s origin and its evolution expose the shortcomings of relying on this approach alone. Continue reading

Spruce Park, Redmond’s Newest Park and Our Neighbor: a horticultural critique

Redmond’s Spruce Park looking NNE from the SW corner toward Gray Butte and Smith Rock in the background. The border beds which follow much of the loop path are ‘native’ plantings according to the conceptual plan. It is common to claim that most of the plants are natives in designed natural areas, but native is not synonymous with ‘natural’. Although natives are used here concessions have been made including such plants as Echinacea purpurea ‘Pow Wow Wildberry’ and Rudbeckia ‘Goldsturm’. In a strict sense Ponderosa Pine aren’t native to this immediate locale either, they require more precipitation than we normally get and the Autumn Blaze Maples are a hybrid of two northeastern North American species.

A landscape, in nature, is a whole, functioning system, capable of perpetuating itself, through out the seasons and years, relying entirely on its own conditions and the cycling of energy and resources occurring on and within it. This is also the definition of a modern sustainable landscape. Ideally they require no inputs or energies supplied from offsite aside from the sun, precipitation and the normal cycling onsite of nutrients and water. A human made, contrived landscape, as all of those built by us today are, may be ‘judged’ by how well they function on ‘their own’, by how well they fit this ideal. Labor and outside inputs necessary to maintain a landscape are then indicators of how out of balance, how far from ‘ideal’ nature and genuine sustainability, a landscape is. A contrived landscape, which ignores the relationships integral to a healthy landscape community ‘demands’ more and more maintenance and support. Given its design and use, a landscape which ignores its site and relationship requirements will deteriorate from the intended design, losing to death component plants while gaining, increasingly, more unwanted available weed species. Design, conditions and use are essential to determine, in this sense, what a ‘good’ landscape is. Continue reading

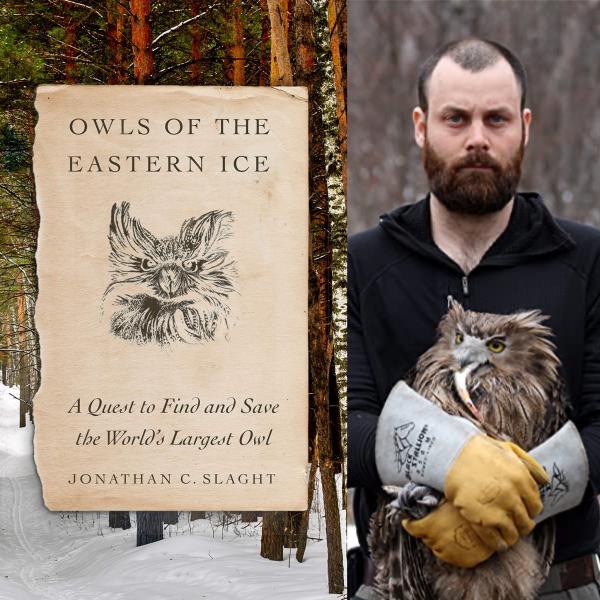

The Owls of the Eastern Ice:A Quest to Find and Save the World’s Largest Owl, Jonathan Slaght, a review

This is a story about the effort to understand and protect Blakiston’s Fish Owl, the largest owl in the world and its endangered population living in the Russian territory of Primorye Krai which lies along the Sea of Japan, north of the Russian port city of Vladivostok. It is a remote, sparsely settled and wild place, isolated from the rest of the world, and Russia as well, at a latitude close to our own, stretching 559 miles, between 42º and 48º north latitude. The author, Jonathan Slaght, a PhD candidate at the time, spent years in Primorye first in the Peace Corps and later working on a variety of wildlife projects before he took on the owls, a several years long study he undertook in association with the University of Minnesota, teaming up with Russian experts, and a loose international group of others doing research on other species resident there, like the Amur Tiger. His crew of Russian field workers, most of them hunters, skilled sportsmen, skilled as well in traveling through the wild landscape and survival there, were invested in the work they were doing. These people become his friends over the several years, despite or maybe because of their quirks, while both assisting and ‘training’ him as they do their primarily winter field work, under very harsh and often dangerous conditions, gathering data in the long months he spent back in the US. Along the way he lays out the work he must do to create an effective conservation plan, the goal of which was to secure the owl’s future, an owl about which relatively little was known. Continue reading

This is a story about the effort to understand and protect Blakiston’s Fish Owl, the largest owl in the world and its endangered population living in the Russian territory of Primorye Krai which lies along the Sea of Japan, north of the Russian port city of Vladivostok. It is a remote, sparsely settled and wild place, isolated from the rest of the world, and Russia as well, at a latitude close to our own, stretching 559 miles, between 42º and 48º north latitude. The author, Jonathan Slaght, a PhD candidate at the time, spent years in Primorye first in the Peace Corps and later working on a variety of wildlife projects before he took on the owls, a several years long study he undertook in association with the University of Minnesota, teaming up with Russian experts, and a loose international group of others doing research on other species resident there, like the Amur Tiger. His crew of Russian field workers, most of them hunters, skilled sportsmen, skilled as well in traveling through the wild landscape and survival there, were invested in the work they were doing. These people become his friends over the several years, despite or maybe because of their quirks, while both assisting and ‘training’ him as they do their primarily winter field work, under very harsh and often dangerous conditions, gathering data in the long months he spent back in the US. Along the way he lays out the work he must do to create an effective conservation plan, the goal of which was to secure the owl’s future, an owl about which relatively little was known. Continue reading