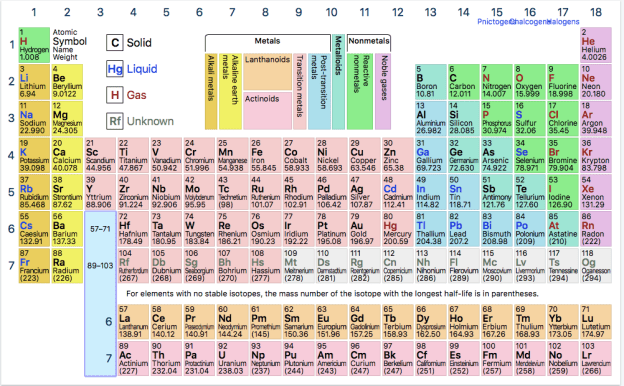

This shows the effected portion of Dry Canyon Park from Antler, at the bottom, where the new municipal well is located, north to the Maple St. Bridge. The Fir connector trail shows up faintly cutting diagonally across the canyon from Fir Ave, 3 blocks north of John Tuck School. West Canyon Rim Park is labelled on the the left. The trail/dam cuts up, northeasterly from it, gray as it is asphalted, faintly in the pic. The water travelled 200 yds north of it, a bit short of halfway up to the Maple Bridge.

I’ve adopted Redmond’s Dry Canyon Park as a project, so I’ve gotten kind of possessive about things that threaten and effect it…but it is a City Park and cities often have competing demands and priorities. In this case the City is under considerable pressure to keep growing. People and businesses are still arriving here at a high rate and this puts demands on its public infrastructure, in this case its water supply. A city of its size also finds itself in need of more Park lands as people’s private space shrinks, population density increases and we all turn to the same limited landscapes for recreation. Compound this with the demand of wildlife and plants for relatively undisturbed landscapes on which they can simply live. Well, this is a case where two of these priorities have come into conflict, and as usual, the utilitarian demands have won out over those for the living natural world (There is no division of the City or local advocacy group, at this point, speaking up for the natural landscape and the life it supports). The utilitarian ‘needs’ of the community are simply a higher priority than those of the natural world. The State is responsible for our water resource and has control over adding new wells and how that is to be done. It is in at least part a health and safety issue. In this role they require that municipalities flush the wells and conduct a flow test to determine rate, drawdown and recovery. This was to be done by running it at full volume 24 hours a day for four days. At 3,500 gals./min. That’s 5 million gals per day. 20 million gals total. That water must go somewhere. It would have overwhelmed our wastewater treatment plant which is running at close to capacity already so it couldn’t be wasted down a manhole…so, it had to be wasted into the landscape of the Canyon itself.

The City contested this amount. This is almost double the amount used by by all residents on a typical winter day of 2.7 million gallons (In summer, due to landscape irrigation the daily amount jumps to 15.8 million gals.). This was all to be ‘wasted’ across the canyon floor. The City had concerns with damage to area infrastructure and paved paths. This requirement was cut in half and eventually to a single 12 hour period as the flooding/washing problem played out. The amount flushed was 2.5 million gals.

April 14, 2024

The filling ‘reservoir’ abutting the north path.

I was unaware of the details of this as I walked the stretch of path this afternoon going north along the west side dirt path, from the trail connector between the main paved trail, extending from the Fir Ave. stairs. I was surprised at all of the surface erosion on and around the dirt path. In some places a foot or more of path had been scoured away, flushed out into the surrounding landscape, its Bitterbrush, Rabbitbrush and other low plants. This erosion continued north following the contours and the trail.

The northern extreme of the test run, where the flow slowed and settled all of the light organic debris.

As the flow spreads and slows larger denser material settles out. Here sediment was deposited in the trail itself and on the ground where the water fanned out.

The flooding had continued a couple hundred yards to where the flow stopped depositing a layer of organic debris the water had carried along.

(I learned on the 17th that this was the result of a test to see what kind of damage might occur and to gauge how the water would spread across the site. This is why the crew was there on the 17th. The test was an attempt to determine the flow pattern so that they could minimize damage.) Continue reading →